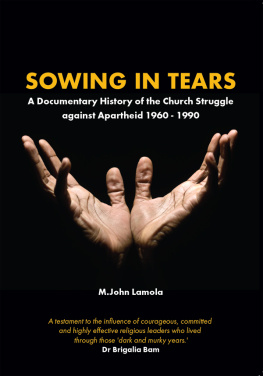

SOWING IN TEARS

A Documentary History of the Church Struggle against Apartheid 1960 - 1990

M. John Lamola

Those who sow in tears

Shall reap in joy.

They who continually go forth weeping,

Bearing seed for sowing,

Shall surely come again

With rejoicing,

Bringing their sheaves with them.

Psalm 126

African Perspectives Publishing

PO Box 95342, Grant Park 2051, South Africa

www.africanperspectives.co.za

African Perspectives Publishing 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and author.

PRINT: ISBN 978-1-990931-24-6

DIGITAL: ISBN 978-1-990931-30-7

Cover Image: Gallo Images/Getty Images

Editor: Tumelo Motaung

Proof Reader: Rose Francis

Graphic Designer: Mfundo Mthiyane

Typesetting: Phumzile Mondlani

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This book project was birthed during the darkest time in the history of South Africa. This period, incidentally, is narrated in Chapter 13. It was 1988. I had just landed in Britain as a depressed and flabbergasted political refugee who bore what felt like an onerous moniker of a Reverend John Lamola. This, at a time when the world was gripped with the news of the arrest of a group of prominent church leaders who, under the leadership of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, had attempted to march to Parliament on 29th February 1988.

I was a young theologian who, in the five years prior, was in the employ of both the South African Council of Churches (SACC) and the Institute of Contextual Theology (ICT). The African National Congress (ANC) community in London and some well-placed leaders in the British Council of Churches had heard of my name.

At the age of twenty-four, whilst a final-year undergraduate student at the University of South Africa (UNISA), I was invited to contribute a chapter on the ethics of violent resistance for a special anthology celebrating Desmond Tutus receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. In May 1987 I was invited by Beyers Naude to join the delegation of the SACC to a conference with the banned liberation organisations in Lusaka, at which occasion I made acquaintance with exiled leaders of the ANC and the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) who, all of a sudden, I found myself having to fraternise with in London. Landing in exile at that juncture of the display of the most radical and determined resolve to bring an end to apartheid by the Christian leadership associated with the SACC, I found myself overwhelmed by church activists and ANC comrades who were keen to decipher the dynamics of the churchs evident leadership of the struggle in South Africa. This was in the aftermath of P.W. Bothas regime having placed all community-based opposition structures within the country under fresh draconian restrictions on 25th February 1988.

The pervasive depression that clouded my mind then stemmed largely from the agony that while I was successfully smuggled out of South Africa, several of my very close comrades were in captivity, facing torture and charges of treason in a Bophutatswana special court. On the other hand, was the angst of settling in exile in the midst of the news of the assassination Dulcie September, the ANC Chief Representative in Paris on 29th March 1988. In the darkness of those days, and the pressure of maintaining a lifestyle dedicated to the momentum of frustrating the apartheid government as an activist political theologian, I stumbled upon a treasure trove of historical documents on the anti-apartheid activities of several church institutions and individuals most of which were in books and journals that were declared banned literature in South Africa.

The first of these was the personal library of Horst Kleinschmidt in his London home. Horst had worked with Beyers Naude at the Christian Institute prior to being forced into exile in the late 1970s. His hospitality earned me the trust of the staff at the International Defence Aid Fund of South Africa (IDAF) who had one of the most sophisticated collections of rare documents about the struggle in South Africa because they were working very closely with the ANC in granting legal aid support to persons back in the country who had fallen into hands of the security police.

At the beginning of 1989 I also discovered an amazing archive of documents on the Black Consciousness Movement at the Selly Oak Colleges library in Birmingham. At that stage, my discoveries and readings were more for my own healing and fortitude. I wallowed into the enlightenment of how the struggle against apartheid colonisation had been prosecuted by those in near-similar professional and personal circumstances as mine.

It was Tony Trew of IDAF who presented an explicit challenge and proposed that I write a book out of the material and reflections that I had progressively shared with him. He indicated that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) would be interested in the publication. The book would specifically be a record of a historicist interpretation of how the Christian religion, whose theology had notoriously been used to foster coloniality and explicitly nurture apartheid philosophy, had transformed itself into an intellectual force and organisational bulwark of the struggle for political change in South Africa.

A nagging complication was that at the time of agreeing to work on this, that is mid-1989, my own level of consciousness had deepened to a point where I was seriously questioning if the monstrous level of the evil and might of the Pretoria regime could effectively be countered by a religious political activism which was largely married to the ideology of nonviolent direct action. In August 1988 agents of the state security apparatus had bombed and destroyed Khotso House, headquarters of the SACC where I used to occupy a little office. What the situation seemed to demand was not another book.

Besides this political pessimism which I had already converted into a theoretical platform whereby against the hype of admiring the heroism of the church-in-struggle, I saw it as my duty to contribute to the ANCs political strategy planning structures a warning that we should tactically view the church not as force of struggle, but as the site for struggle. I was against the church being posited, or regarding itself as the leader of the political struggle. I contested that church leaders inherently lack the scientific attitude required for prosecuting a political struggle to an ultimate revolutionary end.

At that juncture, Jack and Ray Simons of the South African Communist Party, who warmly welcomed me into their home in their curiosity to understand the social power of religion in South Africa, became an invaluable sounding board for my intellectual and spiritual agonies. I had commenced my studies at Edinburgh University, where I incidentally ended up writing a doctoral thesis that questions the efficacy of the epistemology of political theology in delivering the kind of revolutionary social change required in our kind of world. The title of the completed dissertation became The Poverty of a Theology of the Poor: An Althusserian (Louis Althusser) exposure of the philosophical basis of Latin American theology of liberation.

Using original Marxian literature sources, I demonstrated the revolutionary limitations of what was then considered the most radical mutation of Christian theology into a political programme. Having moved away from Theology and now firm in Philosophy, my task of writing a theological appreciation of the rise of the church in South Africa as the epitome of moral radicalness of Christian thought against political injustice, as contracted with Tony Trew, became both a burden and a relished experiment.

Next page