M ichael Larsen was generous with his time and advice and instrumental in organizing two writing groups to which I belong. I am indebted to Michael and to the members of these groups: Richard Bailey, June Johnson, Harlan Lewin, Keh-Meh Lin, Barbara Michelman, Jane Pearson, Brigitte Schulze Pilibosian, Scott Salinger, Steve Sodokoff, Sydney Sauber, and Rolene Walker. Donna Ferriero, Jonathan Silberman, and Frank Sharp suffered through early drafts of the book and provided both encouragement and insight.

Cristen Iris provided expert editorial service, encouragement, and most important, wise counsel. She consistently went above and beyond the call of duty to help get this book published. Danielle Goodman edited an early version of the manuscript and Stacey Smekofske a late version. The defects remaining in the book are solely due to my own shortcomings and refusal to follow advice.

I also owe a debt to many librarians. The Mechanics Institute Library in San Francisco supports writers in a myriad of ways and was a great resource with a welcoming environment in which to work. The librarians of the Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and the Bioscience, Natural Resources and Public Health Library at the University of California, Berkeley, cheerfully helped me find obscure references. The medical library of the University of California, San Francisco, was a resource for many older books and journals.

I am grateful to Jake Bonar and the staff at Prometheus Books for bringing this book to fruition. They were highly professional and infinitely patient with a rookie author.

Anyone interested in vitamins must thank Professor Kenneth J. Carpenter, whose scholarly and encyclopedic history, The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C, is invaluable. It is the first place to go for those who want to delve more deeply into the history of vitamin C.

Of course, I can never sufficiently thank my wife, Susan Semonoff, whose love, encouragement, and forbearance were essential.

|

| Food | Milligrams per Serving |

|---|

|

| Red pepper, sweet, raw, cup | 95 |

| Orangejuice, cup | 93 |

| Orange, 1 medium | 70 |

| Grapefruit juice, cup | 70 |

| Kiwifruit, 1 medium | 64 |

| Green pepper, sweet, raw, cup | 60 |

| Broccoli, cooked, cup | 51 |

| Strawberries, fresh, sliced, cup | 49 |

| Brussels sprouts, cooked, cup | 48 |

| Grapefruit, medium | 39 |

| Broccoli, raw, cup | 39 |

| Tomato juice, cup | 33 |

| Cantaloupe, cup | 29 |

| Cabbage, cooked, cup | 28 |

| Cauliflower, raw, cup | 26 |

| Potato, baked, 1 medium | 17 |

| Tomato, raw, 1 medium | 17 |

| Spinach, cooked, cup | 9 |

| Green peas, frozen, cooked, cup | 8 |

|

An imprint of Globe Pequot, the trade division of

The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2022 by Stephen M. Sagar

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

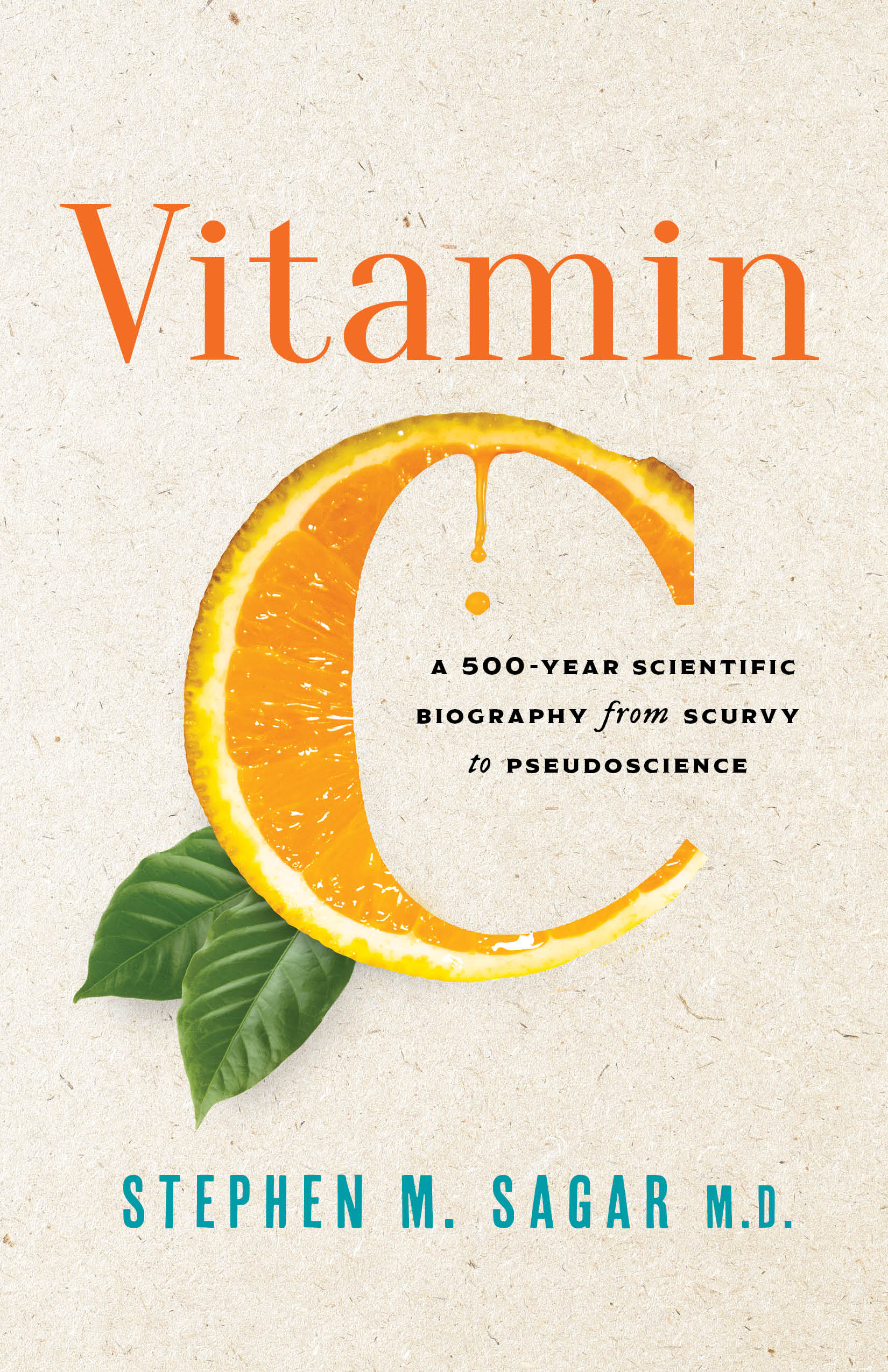

Names: Sagar, Stephen M., author.

Title: Vitamin C : a 500-year scientific biography from scurvy to pseudoscience / Stephen M. Sagar.

Description: Lanham, MD : Rowman & Littlefield, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Vitamin C: A 500-Year Scientific Biography from Scurvy to Pseudoscience is the compelling story of the history and science behind vitamin C Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021060986 (print) | LCCN 2021060987 (ebook) | ISBN 9781633888265 (cloth) | ISBN 9781633888272 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Vitamin CHistory.

Classification: LCC QP772.A8 S24 2022 (print) | LCC QP772.A8 (ebook) | DDC 615.3/28dc23/eng/20211220

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021060986

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021060987

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For Susan

[R]esearch is not a systematic occupation but an intuitive artistic vocation.

Albert Szent-Gyorgyi,

Lost in the Twentieth Century, 1963

I dont think anything is ever just science.

Siri Hustvedt, What I Loved, 2003

CONTENTS

Guide

I first encountered pure ascorbic acid, the chemical name for vitamin C, in 1977. Having just completed medical school and residencies in internal medicine and neurology, I aspired to be a clinician-scientist and went to work in a neuroscience laboratory in Boston. In that job, I used ascorbic acid virtually every day. But I was not interested in the compound; it was merely a substance to prevent the oxidation of other reagents. I did not bother to weigh it out, adding the few milligrams picked up on a spatula tip.

Vitamin C first piqued my interest in the early 1980s when it earned me funding for a pilot research project. One of the Sackler brothers invited my mentor to New York to discuss his laboratorys work. The Sackler family is now infamous for owning Purdue Pharma, promoting OxyContin, and, in the minds of many, igniting the opioid crisis. But that was before OxyContin. The family had gotten rich advising big pharmaceutical companies how to promote drugs directly to doctors. They devoted some of their wealth to a foundation that supported medical research, and my mentor asked his trainees for brief grant proposals to take to his meeting to try to capture some of that wealth for his laboratory.

My proposal concerned the neurobiological actions of capsaicin and, like most writings about capsaicin, contained a statement that it is the active, pungent ingredient of Hungarian paprika and Mexican chili peppers. The Sackler brother who perused the proposal was not interested in capsaicin or in my science. He decided to fund the grant because Hungarian paprika had been a commercial source of vitamin C. Unbeknownst to me, his foundation was supporting the research of Linus Pauling, the Nobel Prizewinning chemist and most publicly visible proponent of megadose vitamin C. My grant proposal had nothing to do with vitamins and nothing of importance came of the project, but this small windfall was one example of the serendipity that punctuated the history of vitamin C.

My research went in other directions and I had little more to do with vitamin C until I switched tracks and entered the pharmaceutical industry. In 2012, I prepared a talk for a job interview at a small biotech company. The same mechanism that transports one form of vitamin C into the brain also transports the drug that I would have worked with at this company. This led me to investigate the neurological manifestations of scurvy and delve into the history of that disease.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.