Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of David T. Bailey,

who told stories well

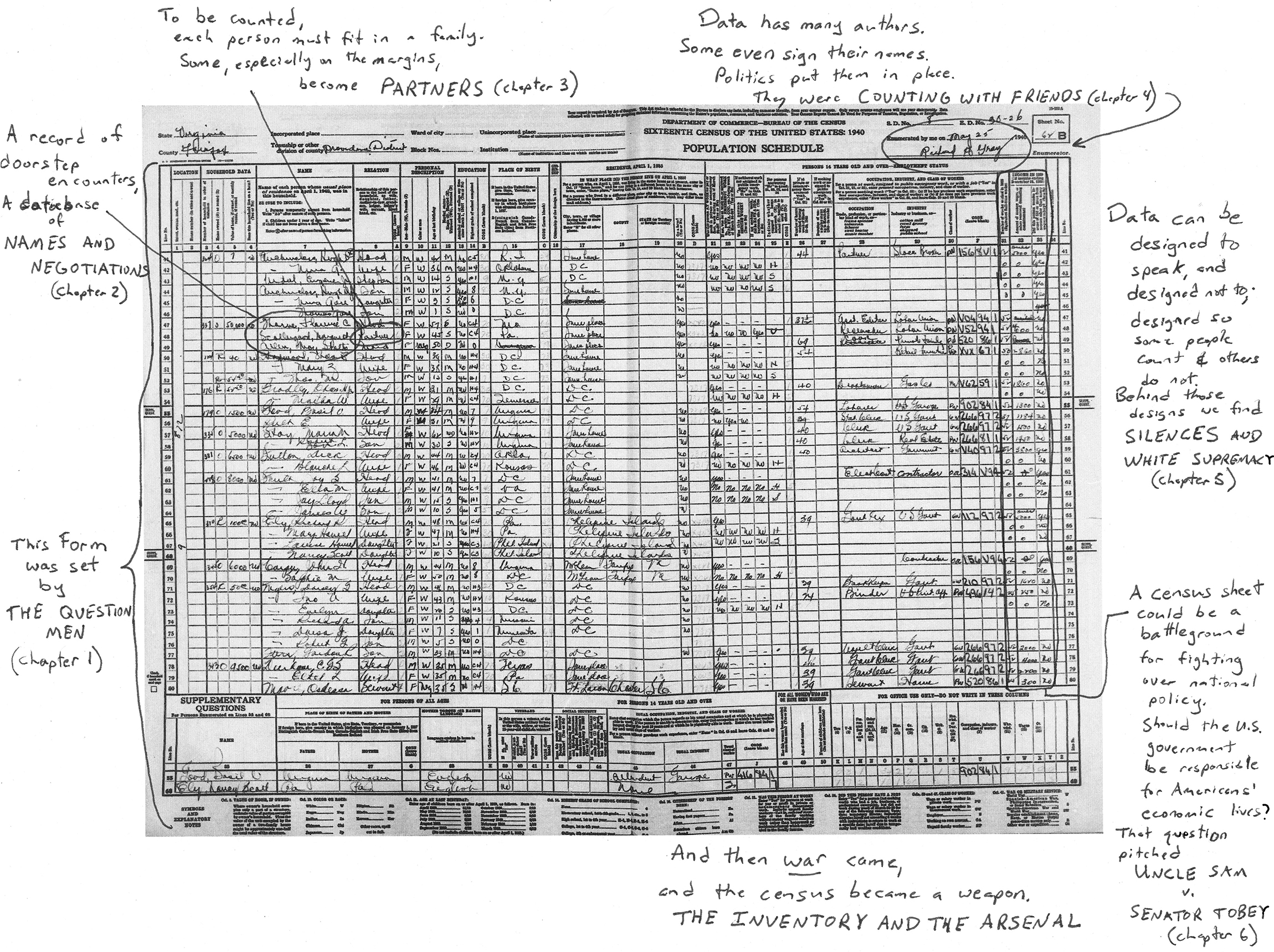

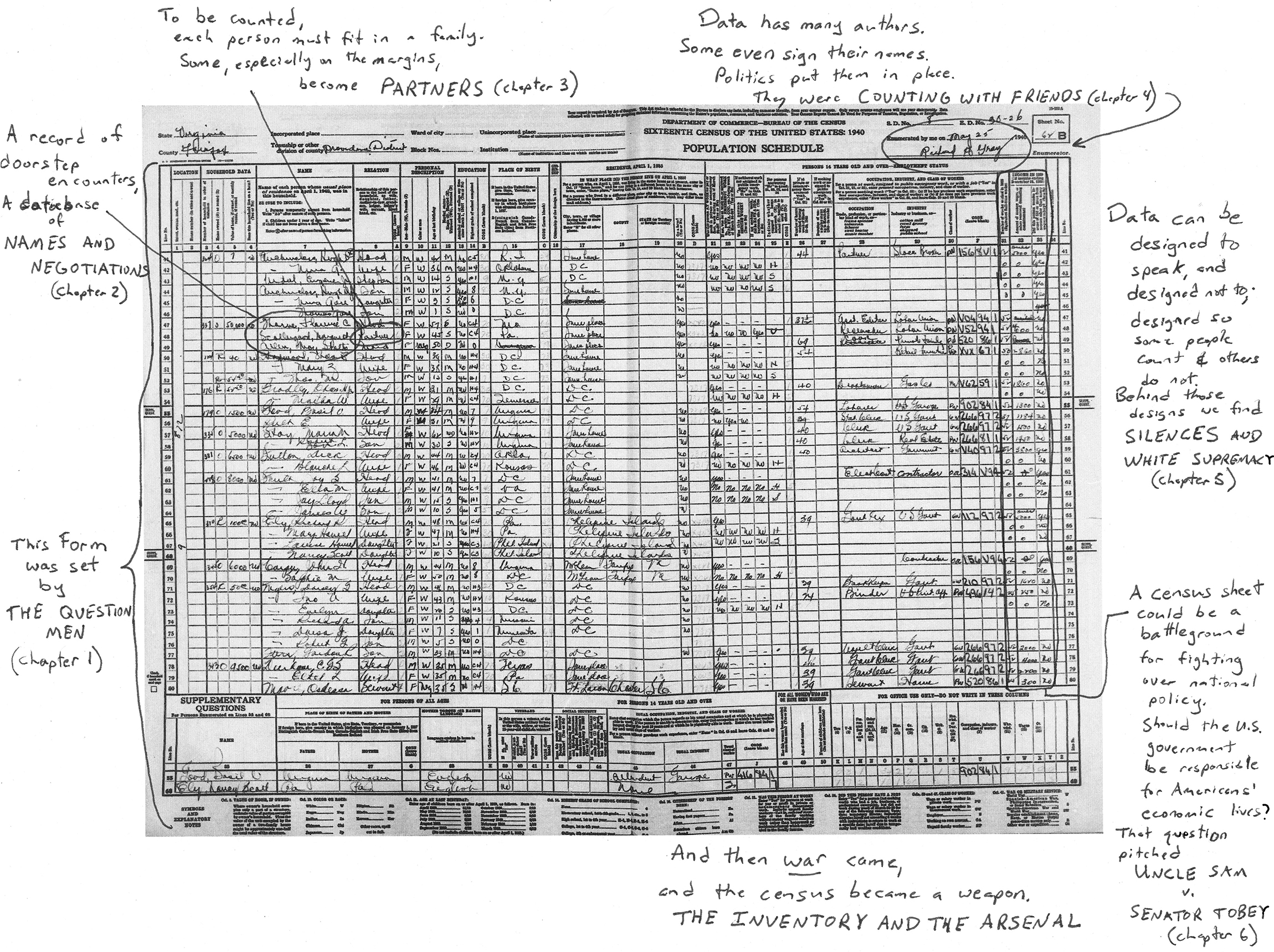

In early 1940, about 120,000 people marched across the United States, through its densest cities, to its farthest reaches. They carried with them large sheets of paper, on which they wrote down, by hand, the details they gleaned or the judgments they rendered about more than 131 million U.S. residents. It was an audacious, astounding effort. (Every decennial population census is.) Its aim was to count and record significant data about each person in the country. (Census takers also gathered data that year about the nations businesses, factories, mines, farms, and homesbut those efforts are not our primary concern in this book. Any mention simply of the census should be understood to mean the every-ten-years census of population.) In 2012, seventy-two years after those sheets of confidential information were first filled in, they became publicly available, as dictated by federal law. (The Census Bureau is barred from releasing any individually identifiable information it collects to anyone, even to other agencies of the government, for a period of seventy-two years from the moment of collection. It can and does publish statistical tabulations right away.) The 1940 census sheets are now accessible on microfilm and in digitized formats, and they are the key source that made this book possible. I have read thousands of these sheets both on my own and working with student researchers employed in my history lab at Colgate University. They offer glimpses into the lives of individuals who might otherwise be lost to history. The sheets also afford a peek into the mundane functioning of a modern democracy, revealing what a government values and how it regards the people it governs.

To fully understand the data inscribed on those sheets required me to investigate the records of the U.S. Census Bureau (what the National Archives calls Record Group 29) as well as the preserved papers of key political officials. It required consulting various government documents as well as databases constructed in later years from census records. In the course of writing this book, I also examined census-related drawings and paintings; I even read a surprising amount of census-inspired poetry. I relied, through it all, on the publications of the census historian Margo Anderson, supplemented by excellent books on the history of racial and ethnic classifications in the United States and other nations censuses. And, of course, I examined the published results and official population statistics released by the Census Bureau. Those results and statistics, published in the 1940s across a series of thick volumes, were the reason that the census was takenthey delivered state population totals that governed the distribution of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, informed government decisions on how to best allocate resources, and inspired discussion and debate about the nations accomplishments, failures, and prospects.

Through it all, I sought to treat those whose lives had been captured in the data with the dignity that each deserved, while I asked the question: what is our democracy, if this is its data?

There are stories in the data. You just have to know how to read them.

Imagine a table of numbers, column after column of digits and decimals gleaming with precision, ornamented only by an aura of objectivity. This is data, to be sure.

Now loosen the hold that image of data has on us. Let in some other visions of how data might be manifested.

Think of a form to be filled in, on paper or a screen, intended to gather information that can later be quantified. That form is like a street corner, a conference room, a transit hub. People and institutions meet on that form. Someone, somewhere designed that form, deciding on the set of questions to be asked or the spaces to be left blank. Maybe they also listed some possible answers or limited the acceptable responses. You then encounter this designed environment as you hunch over the form. Or maybe, instead, a questioner brings the form to the threshold of your home, to your doorstep. That questioner then tackles the difficult task of fitting the unruly reality of your life within the forms straight-ruled lines. The final resulting form and all that is written upon it as well as all the negotiations that shaped it, whether backstage or offscreen, so to speakall of this is data too. The data behind the numbers.

To find the stories in the data, we must widen our lens to take in not only the numbers but also the processes that generated those numbers. When we read these stories in the data, it helps us see the journey that any set of numbers has taken, and it helps us realize that numbers are just one crystallization of a much deeper, richer data setthey are one product of some instrument for making sense of our world, our lives, our societies. Exploring beyond and before important numbers (in our case, the censuss numbers), we see how reading data can reveal deeper truths about our nations systems, our institutions, and ourselves.

I decided to write this book after I started thinking in a new way about an enormous and essential data set that would allow me to read deeply, beyond the numbers. As a historian, I had relied on the U.S. census for years, taking it as a source of facts, and usually taking it for granted. Like most people, I turned to the census more often for numbers than for stories.

Then, one day in 2017, while I was looking for something else in some historical government records, I had an epiphany. I realized that the right sort of investigation could reveal how the U.S. government in the course of a census translates people into data; it could also help us all understand better how individual people, families, communities, and the nation are transformed by counting.

I believe in the census, the way I believe in democracyin part because in the United States the census and democracy are intimately intertwined. The numbers the census churns out represent the people to the government, and they shape the political representation those people enjoy. As long as the people to be counted have a significant say in what matters and how the numbers will be used, then the census overflows with democratic potential. As long as the people control their own enumeration, then the quest to count each person is one of the purest expressions of democratic values.

As my epiphany unfurled, I saw how the census stood waiting to help us understand the democratic potential of data.

Actually, the historical censuses stood waiting to help. You see, the census holds its cards close to the vest, protecting fiercely for seventy-two years everything apart from its published results. (Those results range from reports of each states population to more specific tables showing local totals within a state or numbers arranged by age or by income levels or by a whole host of possible categories. All those tables fill thousands of printed pages or electronic spreadsheets, and yet they still tell only a tiny fraction of the whole story.) If I wanted to read deeply, beyond the numbers, I would need to look to the past, to an already-unlocked census. In such a census I could read not only the published statistical tables but also the manuscript materials recording millions of interactions and the asking and answering of billions of questions. In such a census I could peer into the deliberations of its designers, dig into records of the debates of politicians and the machinations of elites, and investigate the uses and abuses of the data at every stage of its creation.