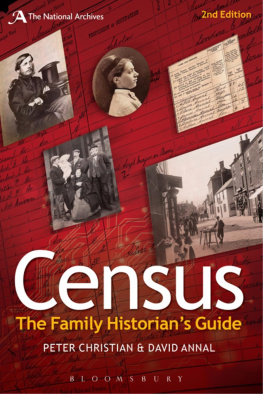

C ENSUS

THE FAMILY HISTORIANS GUIDE,

SECOND EDITION

Peter Christian and David Annal

BLOOMSBURY

LONDON NEW DELHI NEW YORK SYDNEY

First published in the United Kingdom in 2008 by

The National Archives Kew, Richmond Surrey, TW9 4DU, UK

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

The National Archives logo Crown Copyright 2014

The National Archives logo device is a trade mark of The

National Archives and is used under licence.

Text copyright Peter Christian and David Annal, 2014

The right of Peter Christian and David Annal to be identified

as the Authors of this work has been asserted by them in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

London, New Delhi, New York, Sydney

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the Publisher.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organisation

acting or refraining from action as a result of the material

in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Publishing

or the authors.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

First Edition ISBN: 9-781-9056-1534-6

Second Edition ISBN: 9-781-4729-0293-1

Design by Fiona Pike, Pike Design, Winchester

Typeset by Saxon Graphics Ltd, Derby

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Photographic credits: Crown copyright UK Government Art

Collection; , and , The Mary Evans Picture Library; ,

and , The Illustrated London News (which can be seen at The

National Archives in ZPER 34/98). All other images are from

The National Archives and are Crown copyright.

C ONTENTS

On 2 January 2002, a remarkable event occurred which thrust the previously quiet and peaceful world of family history research into the glare of the national media. An ambitious plan to make the records of the 1901 census for England and Wales available online proved a victim of its own success when thousands of family historians who had been waiting ten years for its release and many others, inspired by press coverage but with perhaps no more than a passing interest in the subject, logged on to the 1901 census website causing it to crash within hours of its launch. The 1901 census included the details of more than 30 million people, and this was the first time that an attempt had been made to provide access to such a large volume of family history data via the internet. Earlier censuses had been made available on microfilm and although each successive release had provoked excitement and interest in the family history community, no previous census release had captured the attention of the national press in quite the same way.

The experience of the 1901 census release, together with advances in online technology, led to a successful and trouble-free launch of the 1911 census. As a result of a ruling made under the Freedom of Information Act, the National Archives released the 1911 returns for England and Wales early that is, before the customary 100 years had passed. The records were released gradually, county-by-county during 2009, and are now fully available online.

The release of the 1921 census is (at the time of writing) some eight years away, and as the terms of the 1920 Census Act mean that the records will not be released early, family historians will have to be patient for a while yet.

But why is such importance attached to census returns? Why does the release of another set of census records provoke such avid, some might even say obsessive, interest? What is it about the census that has led to questions being asked on a number of occasions in the House of Commons? This book will attempt to answer these questions, as well as explaining what the census is, how and why it was taken, and most importantly how researchers can use, understand and access the returns today with the focus on online research.

Census returns are one of the key nineteenth-century sources for family historians, delivering a wealth of information about their ancestors including names, addresses, ages, family relationships and occupations. The documents may appear on the surface to be quite straightforward, but the process by which they were compiled means that the unwary researcher can easily fall foul of them. This book aims to help you navigate your way through the census returns and show you how to avoid the major pitfalls.

We begin with an exploration of the origins of the census in . Although there are broad similarities between it and its Victorian predecessors, the layout of the schedules, the range of questions asked and, perhaps most importantly, the process that led to the creation of the records are different enough to warrant a separate chapter.

In we explain why finding your ancestors in the returns isnt always as easy as it might be and we will offer some advice to help you to untangle these problems.

The book then goes on to explain how to access the census returns. Chapters 5 to 7 cover the census online, what you can access for free, and the best techniques to maximise the success of your searches. Chapters 8 to 15 take you on a guided tour of the most important census websites. Appendix A looks at the advantages and disadvantages of each of the sites and helps you to decide which best suits your needs.

For the most part, the book deals with the census returns for England and Wales, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, which were taken every ten years from 1841 to 1911 essentially the records held by The National Archives of England and Wales. The Scottish census is generally treated alongside the English one because it is similar in most respects while reference is made to Ireland, highlighting the significant differences, in the relevant chapters. explores the most important websites for accessing the surviving Irish censuses.

Chapters 16 and 17 cover topics that may seem old-fashioned, but will still be incredibly useful for some researchers. we will take a brief look at some of the offiine search tools available to help you to access the census on microfilm. Some people prefer to access the returns this way and in certain cases it might be the best option for you.

Serious researchers will want to ensure that the results of their work are fully accessible and that the sources they use are correctly cited. explains how the various National Archives referencing systems work and provides a guide to citing census returns.

Lastly, the book assumes that most readers are interested in census returns from a family history perspective, but we need to remember some important points here. Firstly, the census was not taken with family historians in mind; the arrangement of the returns and the information they record may sometimes make us feel that this was the case but we have to put that idea out of our minds. The census returns were taken by the government of the day for a variety of social and political reasons, which we will explore below. Also, although family historians may form the main body of users today, we must not ignore the requirements of academics and local historians; the census returns can be vital to their research and this book is aimed at them too. To that end, takes a look at the supplementary sources that researchers can access to help provide a more in-depth understanding of these remarkable records. Appendix B contains a list of the dates of all the UK censuses together with some useful notes regarding their status.