First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PEN & SWORD FAMILY HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Emma Jolly 2013

PAPERBACK ISBN: 978 1 78159 061 4

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47383 075 2

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47382 959 6

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47383 017 2

The right of Emma Jolly to be identified as Author of the Work

has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Palatino and Optima by

CHIC GRAPHICS

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK), Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword

Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Pen and Sword, especially Rupert Harding and Simon Fowler for suggesting that I write this book, and to Steve Williamson for his careful editing. I am further grateful to Simon for reading the full manuscript and making invaluable suggestions. Thanks also to Barry Jolly, Charlotte Jolly, and genealogists Celia Heritage and Chris Paton for their reading and useful comments.

Finally, thank you to Simon, Jacob and Oscar for putting up with domestic chaos and teaching me all I needed to know about Jedi Knights.

Chapter 1

HISTORY OF THE CENSUS

F amily historians have been using census records for over forty years. Often referred to as genealogys most useful resource, the census became central to popular family history when searchable records were placed online in 2002. Before this, genealogists and other researchers had to search painstakingly through reels of microfilm to find their ancestors. Now transcriptions and images of the 18411911 censuses can be explored from the comfort of a home computer or at a local library. However, the census was never intended for the use of family historians. Some censuses have been destroyed deliberately over the years, whilst others have been damaged in war, or through the damp and decay of poor storage. Where censuses have survived, it is often due to a chance event or the intervention of an official concerned with demographic, socio-economic or political factors. Censuses, in some form, date from early history, but family historians are most concerned with those created in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This book will explore these, and look at how family historians can best use them for their research.

What is a Census?

According to the Oxford New Shorter English Dictionary, a census is defined as:

n. & v. E17. [L, f, censere assess: cf. CENSE n.] An. A tax, a tribute; esp. a poll tax. E17M19. Hist. The registration of citizens and their property in ancient Rome, usu. for taxation purposes. M17. An official enumeration of the population of a country etc., or of a class of things, usu. with statistics relating to them. M18 Bv.t. Conduct a census of; count, enumerate. L19.

The E17 in this definition suggests that the use of the word census in English dates only from the early seventeenth century. However, the use of the Latin term cense dates from the days of the Roman Empire. Through the Bible, Britons were aware of the Roman census, although not necessarily of its full significance. Christians marking the birth of Jesus each Christmas were familiar with the words from the Gospel of St Luke (2, 13):

And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed. (And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria.) And all went to be taxed, every one into his own city.

This census of circa AD 0 was thus the alleged reason that Jesuss mother Mary and her husband, Joseph, were travelling from Nazareth to Bethlehem, where the baby was believed to be born. At the time, citizens of the Roman Empire had to register for the census in their place of family origin. As Joseph was descended from the line of David, he had to register in Bethlehem, the town of David in Judea. Historians have questioned this, arguing that no such movement of peoples was required. Nevertheless, the Roman census was taken quinquennially between 550 BC and AD 14. Before the mid-fourth century BC, the statistics are regarded as unreliable.

The earliest recorded census was of Mesopotamia in 3800 BC under the command of the King of Babylonia. The purpose of all the early censuses was to establish resources of both finance and human beings. The Babylonians recorded the number of pigs, amongst other produce in their lands, whilst the Romans monitored numbers of men available for taxation purposes, as well as for their extensive armies.

In the seventh century AD, a census was taken of the kingdoms of the Dal Riata, the Gaelic lands that now form part of Scotland and Northern Ireland. This census is contained with royal genealogies in the Senchus Fer n-Alban (History of the Men of Scotland), and reveals how the population was divided within fiscal and military groups.

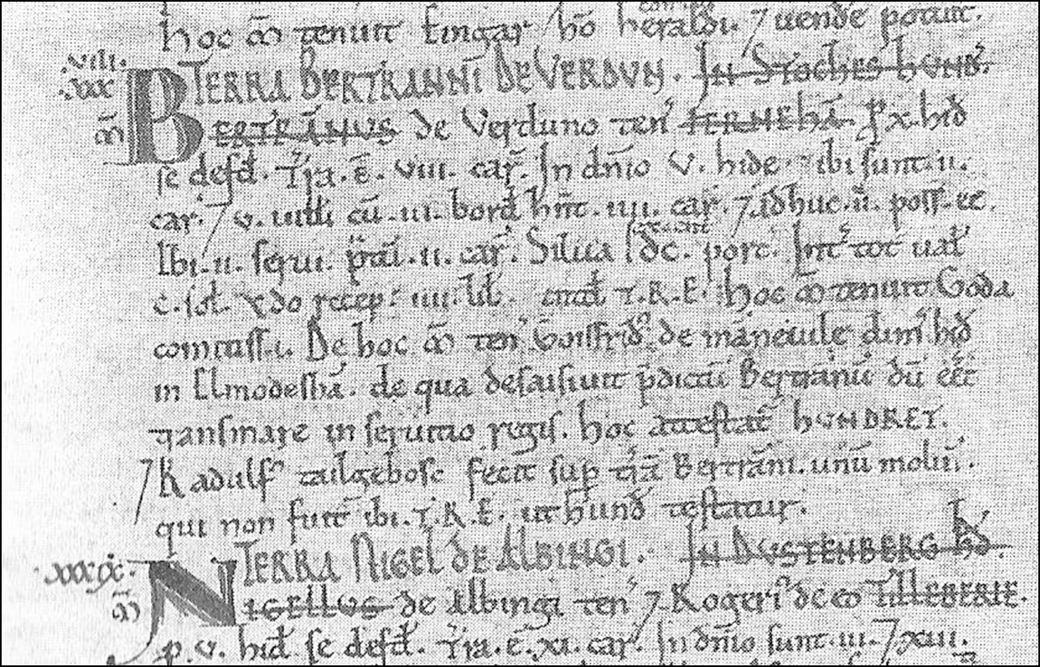

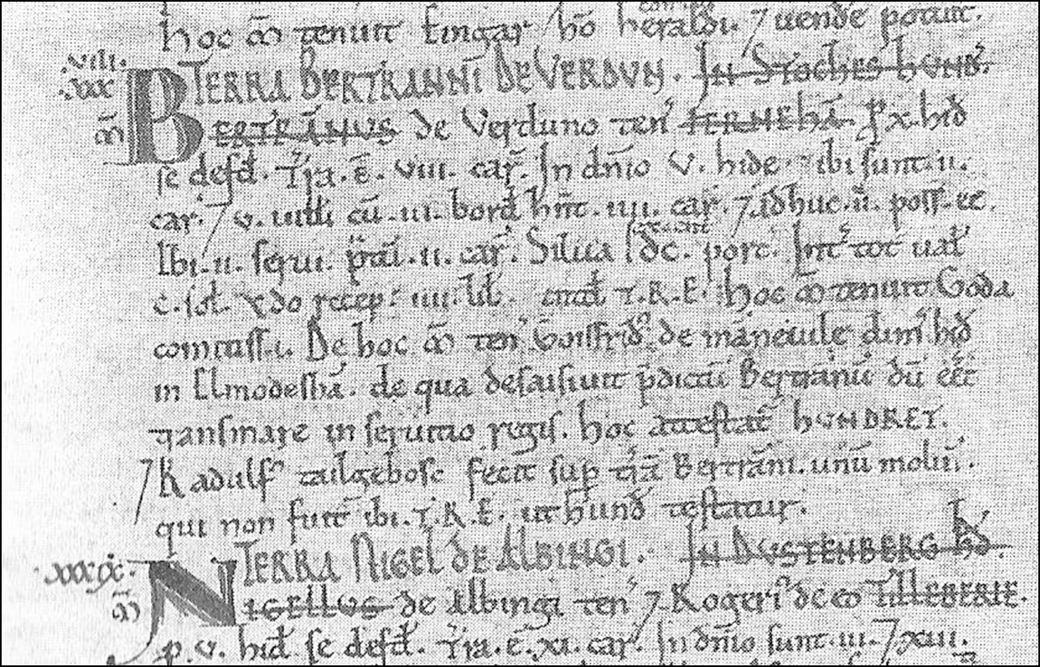

Like the rulers of Babylon and of Rome, after William the Conqueror had settled in England, he wanted to establish the numbers of men and resources available to him. This resulted in a form of census known as the Domesday Book, the original of which is held at The National Archives. The assessment, begun in 1085, recorded 13,418 settlements of the counties south of the rivers Ribble and Tees. Over twenty royal commissioners acted as census enumerators in seven circuits (regions). It concentrated on the kings property and land, providing details of the nature of the land, any buildings and the resources of the land (e.g. fish, animals, plants). A jury of local people gave the names of the landholders (tenants-in-chief), tenants and undertenants to the royal commissioners. The social position of the tenants as villagers, smallholders, free men or slaves was also identified. Urban entries include records of traders.

A page from the Domesday Book showing the entry for Bertram de Verdun.

Not everyone was included. Only heads of households were recorded and notable absences from the book are nuns, monks, people living in castles, as well as the inhabitants of London, Winchester, Bristol, the borough of Tamworth, and the lands that became Westmoreland, Cumberland, Northumberland and Durham. The book remained incomplete: work on the survey was abandoned in 1087, during the reign of William Rufus.

In 1676 the Bishop of London, Henry Compton, initiated an ecclesiastical survey of individual parishes. The Compton census, as this is commonly known, aimed to discover an estimate of the numbers of Anglicans (Conformists), Catholic recusants (Papists), and Protestant Dissenters (Nonconformists) in England and Wales. As may be expected from this early census, results were inconsistent. The incumbent was asked:

Next page