This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1997 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

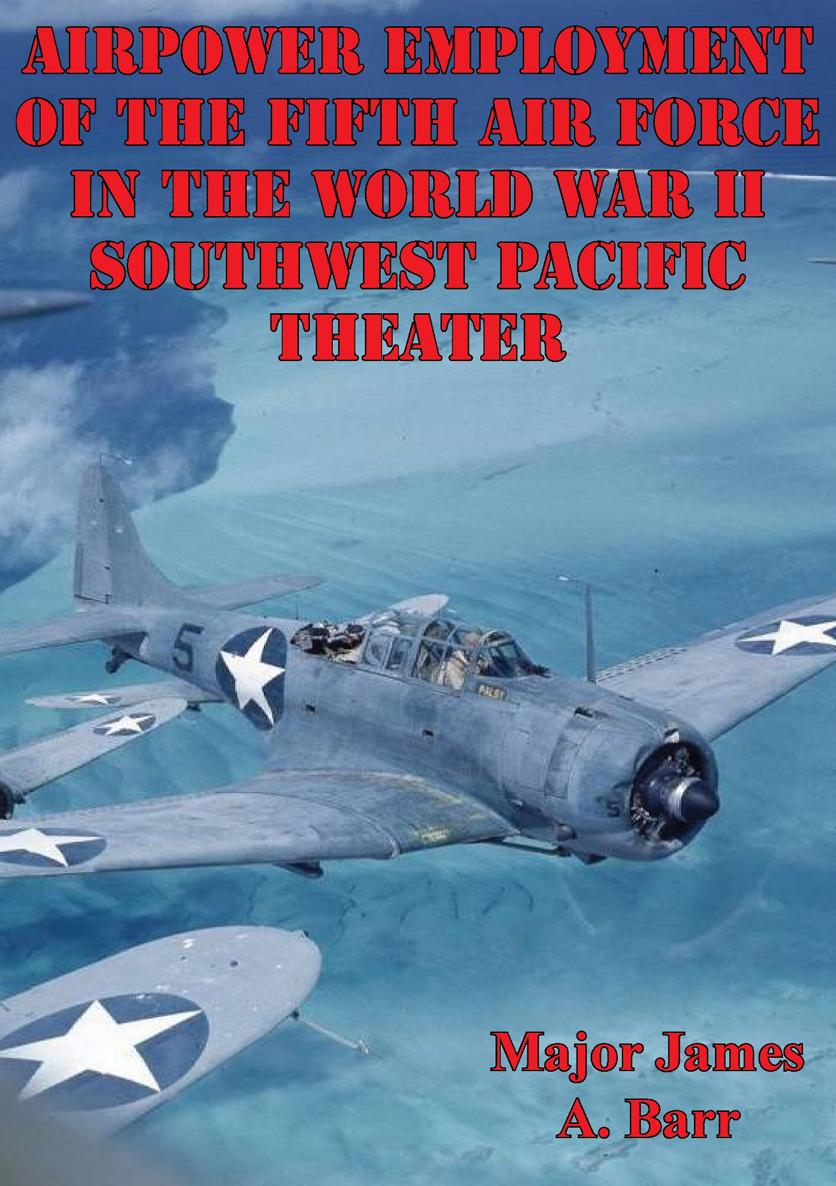

AIRPOWER EMPLOYMENT OF THE FIFTH AIR FORCE IN THE WORLD WAR II SOUTHWEST PACIFIC THEATER

by

Major James A. Barr

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank my Air Command and Staff College research advisor, Lt Col Ernest G. Howard, for his time and effort in guiding me through the research process. His experience and wisdom helped me bypass several hurdles along the way.

I would also like to thank Mr. Joseph Caver and the rest of the staff at the Air Force Historical Research Agency. Their patience and assistance were very helpful in finding and sifting through many boxes of documents.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ABSTRACT

This research project studies the employment of airpower by the Fifth Air Force, under Gen George C. Kenney, in the Southwest Pacific Theater during World War II. The research began with two basic assumptions. First, it assumed that the strategic bombardment theory developed by the Air Corps Tactical School in the 1930s was the definitive doctrine of the Air Corps upon entry into World War II. Second, it assumed that General Kenney and his staff were required to develop a new doctrine for airpower employment since the situation in the Southwest Pacific did not lend itself to strategic bombardment of the Japanese industrial web. The research process proved both of these assumptions invalid.

Study of historical records, personal accounts, and subsequent historical writings in several areas revealed that there was no clear and consistent doctrine for the employment of airpower. The views of the War Department General Staff were divergent from the strategic bombardment doctrine developed within the Air Corps. There were influential individuals within the Air Corps itself who did not agree with the degree of subordination of all other forms of aviation to bombardment. These facts created the situation where published regulations concerning airpower were inconsistent and incomplete in their statement of doctrine.

General Kenney assumed command of the Fifth Air Force with a clear vision of how to employ air forces to defeat the enemy. His diverse background gave him a balanced view of the roles airpower should play, and he was not convinced by the strategic bombardment theory that claimed invincibility for the bomber. His World War I experiences and teachings at the Air Corps Tactical School provided a strong belief in the importance of air superiority and attack aviation. He was innovative in modifying tactics and equipment, and in developing new roles for airpower as the situation dictated. General Kenney and his staff did not need to develop a new doctrine for use in the Southwest Pacific. He simply applied the experiences of a diverse career and organized an effective, balanced weapon to wage war.

This study surveys the development of airpower doctrine beginning with World War followed by major developments during the interwar period in several arenas. It then looks at the varied aspects of Gen George C. Kenneys career which prepared him to command the Fifth Air Force in the Southwest Pacific Theater during World War II. Finally, it considers General Kenneys employment of airpower in light of the pre-war doctrine development.

CHAPTER 1 PRE-WORLD WAR II AIR DOCTRINE DEVELOPMENTS

World War I Developments

When the United States entered World War I, it was ill-prepared to support the war effort with airpower. It had not developed or produced any modern combat aircraft since the war had begun in Europe. Maj Raynal C. Bolling, heading an aeronautical commission, went to Europe to identify aircraft requirements. The report, filed on 15 August 1917, established the doctrinal and force structure basis for building the Air Service. Major Bolling reported that aircraft were required for training, support of ground forces in the field, and an air force component used independently of the ground forces.

General Pershing convened a board in 1919, under Maj Gen Joseph T. Dickman, to provide lessons learned from each branch of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). The Dickman Board reported that Air Service AEF had evolved into the four roles of observation, distant reconnaissance and bombing operations, aerial combat, and combat against ground troops. The board stated that air combat against ground troops had not been sufficiently developed, but that it could be made more important than independent distant bombing operations. The air leaders of the time almost unanimously expressed that the Air Service should be subordinate to the ground forces. In his Final Report of the Chief of Air Service A.E.F., Gen Mason M. Patrick claimed that separating air forces from other components of the army would sacrifice the cohesion and unity of effort which alone distinguishes an army from a mob. Even the manual of operations that Gen William Mitchell issued in December 1918 as Air Service Commander, US Third Army, visualized aviation in a support role for the infantry rather than as an independent force. {1}

Although air forces were not independent, it is evident that most airpower missions used by Gen George C. Kenney in World War II had been identified in World War I.

Political Post-War Environment

While the Army was trying to incorporate lessons learned from World War I, popular opinion toward the military in the United States following the war was similar to that experienced worldwide. There was strong anti-war sentiment following the years of trench warfare, and the general consensus of the American public was for a return to isolationism. After the crusade was over in 1918, Americans for the most part wanted to return to refuge behind the protection of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. As a result, research and development were greatly affected, and World War I aircraft technology was state-of-the-art in the United States military into the early 1930s. War Department plans emphasized maintaining a small force with a balance of air and ground forces, depending on a full mobilization if the United States was attacked. {2} The publicly stated policy up to the advent of the United States entry into World War II was one of defense of American continental shores and overseas possessions. {3} Consequently, a study of the development of airpower doctrine and technology must consider this strategic environment, where offensive operations went against national policy.