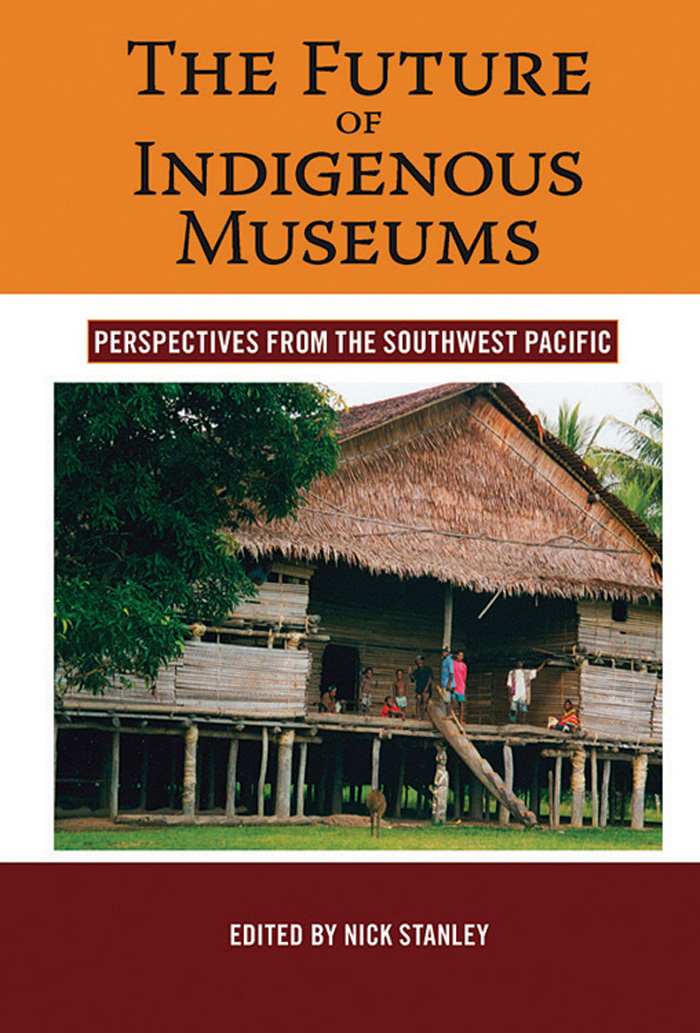

The Future of Indigenous Museums

The Future of Indigenous Museums

Perspectives from the Southwest Pacific

Edited by

Nick Stanley

First published in 2007 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2007, 2008 Nick Stanley

First paperback edition published in 2008

First ebook edition published in 2013

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages

for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book

may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information

storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented,

without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

/ edited by Nick

Stanley.

p. cm. -- (Museums and collections ; v. 1)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-84545-188-2 (hbk : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-84545-596-5 (pbk : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-85745-572-7 (ebk)

1. Ethnological museums and collections--Oceania. I. Stanley, Nick.

GN36.O34F87 2007

069.0995--dc22

2007021965

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-84545-188-2 hardback

ISBN 978-1-84545-596-5 paperback

ISBN 978-0-85745-572-7 ebook

Contents

Nick Stanley

Lissant Bolton

Sean Kingston

Diane Losche

Tate LeFevre

Anita Herle, Jude Philp and Leilani Bin Juda

Eric Venbrux

Haus Tumbuna Sebastian Haraha

Alison Dundon

Christin Kocher Schmid

Nick Stanley

Robert L. Welsch

Christina Kreps

List of Figures

2.1 Moro figure captured by MEF forces, July 2000.

(Photo: Robert Irogo. Permission: Solomon Star.)

2.2 MEF forces with Moro figure, July 2000.

(Photo: Robert Irogo. Permission: Solomon Star.)

3.1 The mother tubuan: the most dangerous, and most ramifying, presentation of heritage in southern New Ireland.

(Photo: the author.)

3.2 Dancers wearing kabut: these are lesser incarnations of tubuan, which evoke correspondingly smaller segments of the past.

(Photo: the author.)

3.3 Some tonger readied for the exchange of pigs and the dismantlement of the social relations they visualize.

(Photo: the author.)

3.4 A lalamar, shell-money body of the deceased, prior to its disassembly and the finishing of thoughts of the departed. Note the small photograph of the deceased tied to it.

(Photo: the author.)

6.1 Opening ceremonies outside the Gab Titui Cultural Centre. Church leaders, elders, community and visitors all joined in to bless Gab Titui.

(Photo: George Serras, National Museum of Australia, 2004.)

6.2 Biship Mabo blesses the Gallery in anticipation of its first visitors.

(Photo: George Serras, National Museum of Australia, 2004.)

6.3 Badu Goigal Pudhai Dancers with aeroplane headdress depict Second World War air attacks over Torres Strait.

(Photo: George Serras, National Museum of Australia, 2004.)

9.6 Iniwa Sakema, the Kini Cultural Centre, in 2000.

(Photo: the author.)

10.3 Mr Otali Amot receives money from the Australian High Commissioner for handing in his luluais hat, 1994.

(Photo: the author.)

Editorial Preface

I am pleased that my article Indigenous Models of Museums in Oceania (Museum (1983) 138: 98101) has had such a long-term impact. When I wrote that essay I argued that there was a distinctive difference between indigenous models and Western exemplars. Over the past twenty years this divergence has become more apparent as people in the Pacific have been reassessing and accessing indigenous culture.

There are now two forms of indigenous museums. The first is a single-purpose building. I saw a good example in Taiwan of an indigenous museum for the Atayal Tribe. It consisted of a three-storey structure to tell their story from prehistory to modern times. The other form of indigenous museum is a multifunction tribal culture centre that includes a variety of functions and purposes according to the needs of the particular groups. Here in New Zealand several tribal groups are planning to build tribal culture centres. Our tribe, Ngati Awa, is one of them. We intend to have a museum to tell our story and to house some of the tribal heirlooms and icons that we still have in our possession. In addition, however, we intend to include a photographic section, an audio section, a library, a research facility, a whakapapa section, a lecture room, a modern art section and some art workshop areas. The government is taking an interest in tribal culture centres and so we might see some actually taking shape. An important requirement is that indigenous people should be the guardians, protectors and advocates of their own cultures and their own cultural heritages. A variety of cultural centres, small and large, run by indigenous people meets this need. Tribal groups here in New Zealand are excited by the idea and by the challenge. One group has managed to find the required funding for their culture centre. The rest of us look to government funding to assist us. As yet it is unclear whether the government will fund at a level that will enable us to make a start.

I fully support this project to publish a volume of papers that explore the notion of indigenous museums.

Hirini Mead

Ngati Awa Research

New Zealand

Introduction: Indigeneity and Museum Practice in the Southwest Pacific

Nick Stanley

Over the past decade or more the Southwest Pacific has provided a type of laboratory for new cultural developments. For the study of culture, particularly in material form displayed in museums, the region has, as in the eighteenth century, offered novel perspectives to scholars and the public both in the region as well as elsewhere in the world. This book examines the growth of cultural centres in the area and seeks reasons both for their genesis and their continued popularity. In so doing the authors here are following up a landmark publication, Soroi Eoe and Pamela Swadlings 1991 study entitled Museums and Cultural Centres in the Pacific. Eoe and Swadling solicited contributions from over forty different locations across the Pacific. Each provided a pithy account of the salient features of their respective centre. Eoe and Swadling have provided the region with a benchmark against which to measure subsequent developments. This volume studies many of the same locations as the earlier study but with some notable differences. Firstly, the field of study is narrower: the focus is on Melanesia, excluding Micronesia and Polynesia. The study also includes three groups to the west of Melanesia, around the Arafura Sea: the Tiwi of Melville and Bathurst Islands in the Australian Northern Territory, the Torres Strait Islanders, and the Asmat of West Papua. The intention is to provide greater space for authors to develop the theme of the growth of indigenous museums and cultural centres in a more geographically specific region, and thereby, hopefully, to indicate the linked thinking and practice that unites them.