THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1956 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1956

Paperback edition 1958

Printed in the United States of America

02 01 15 16 17 18

ISBN: 978-0-226-22919-5 (e-book)

ISBN: 0-226-16779-8 (paper)

LCN: 56-13050

This book is printed on acid-free paper

He that hewed timber afore out of the thick trees: was known to bring it to an excellent work. Psalm 74, verse 6: Book of Common Prayer

Foreword

THIS IS A VERY simple book. It is offered to thoseand, of course, they are many in these busy dayswho, if they were suddenly asked just what the name of Alfred the Great meant to them, would promptly answer with one or more of the following: He conquered the Danes, whoever they were in those times. Wasnt he the king who burned some cakes in some womans cottage? He dressed up as a minstrel and spied upon the enemys camp. He cut out White Horses in the hills to celebrate his victories. The tower in the park, the tearoom in the village, the statues in some towns, and the daffodils in my garden are named after him. Didnt he translate some old books? Was he the king who started Englands navy? Did he invent trial by jury? All these answers are honored by tradition; they rest, some on truth, some on romanticism; and all are dealt with here in their proper places.

In the late nineteenth century the historian John Richard Green wrote of this king of Wessex: The love which he won a thousand years ago has lingered round his name from that day to this. While every other name of those earlier times has all but faded from the recollection of Englishmen, that of lfred remains familiar to every English child. I doubt whether Greens statement is true of today.

Anglo-Saxon England, the England before, during, and after Alfreds time, has been splendidly described within recent years. One has only to mention, among those known for the revealing of its history, the names of Sir Frank Stenton, of R. H. Hodgkin, of Sir Arthur Bryant, of Dorothy Whitelock, of Peter Hunter Blair, of D. J. V. Fisher, and of John Pope.

There are also many Lives of Alfred in our libraries. But the best of these biographies were written many years ago, before the writers mentioned above had given us their views based upon their research. Perhaps, then, this book, which gladly acknowledges its debt to them, will not be out of place among those who grew up, or did not grow up, with the legends of Alfred the Great at school. It has three aims: to do what it may in spreading among us the knowledge of this king who did so much for his England and his world; to place him in his settingSaxon, Celtic, and Continental; and to build his story on simple lines, which rest nevertheless upon a foundation suggested by the sources given at its close.

As with my former books on Anglo-Saxon life and personalities, many friends and scholars on both sides of the Atlantic have here once more given me that help and encouragement for which I am deeply grateful. For invaluable criticism of this book in typescript I wish to thank especially Bruce Dickins, Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge.

E. S. D.

CHAPTER ONE

Wessex BEFORE THE TIME OF ALFRED

THE NINTH CENTURY in all its course was the century of Alfred the Great. Its first half, from 800 to 849 A.D., saw, as it were, the preparation of the theater, the gradual building of the background, in England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, in France, in Germany, in Scandinavia. Against this background, of invasion and of war, of destruction and of lawlessness, of constant struggle on English soil between the foreign intruder and the native-born, of ignorance deep and universal, ignorance concerning the things of God and of man, this king played his leading part, and for the high manner of his playing stands alone among the rulers of English land.

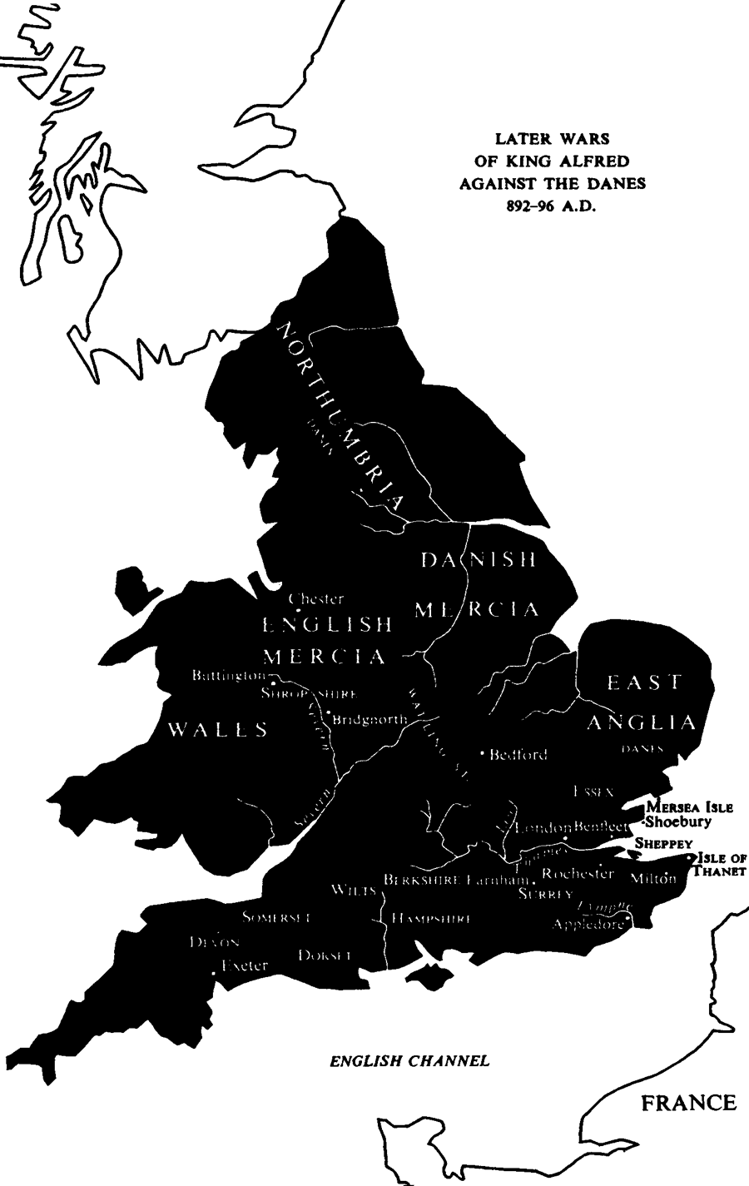

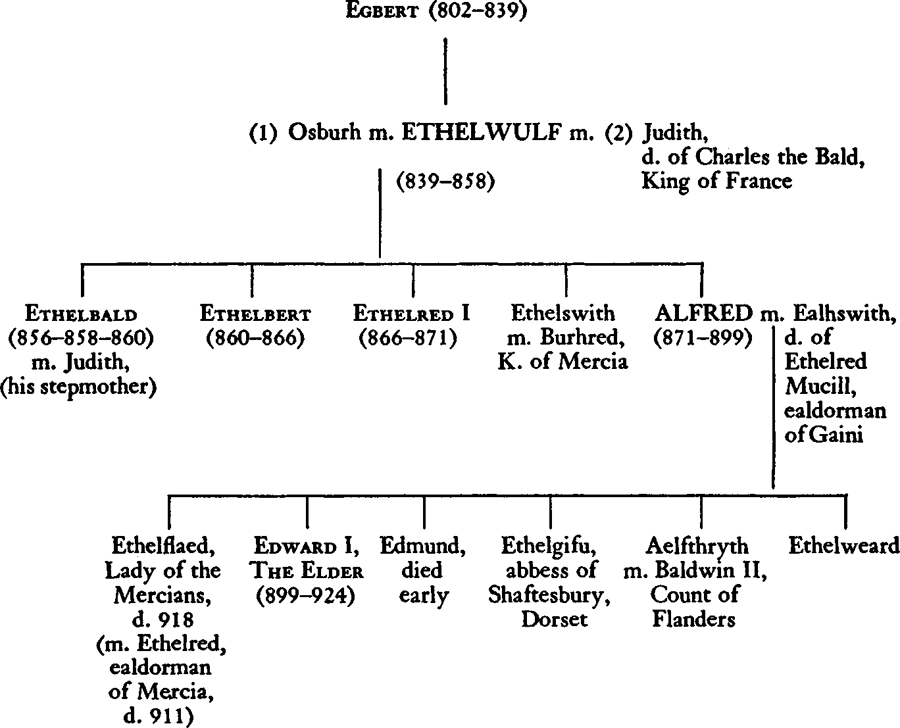

We begin our story, then, in the first years of this ninth century: in 802, to be exact, the year in which Egbert, Alfreds grandfather, came on the scene as ruler of Wessex, the kingdom of the West Saxons. As its king he governed in the south and west of England the shires of Somerset, Dorset, and Devon, Wiltshire and Hampshire. In Cornwall the Celtic British were still holding out against West Saxon conquest, and Berkshire was a debatable region, swaying between West Saxon and Mercian control.

In these years, indeed, the word Mercian meant much to Wessex, for the kings of Wessex, one after another, acknowledged the supremacy of Mercia, the Midland kingdom of the Trent Valley. This power of overlordship had been won during the previous, the eighth, century by those great rulers of Mercia, Ethelbald and his more famous successor, Offa. Offa, as king of Mercia, at his death in 796 had been not only lord of Mercia proper, in the lands of Stafford, Derby, Nottingham, Warwick, Worcester, and Leicester. His power as supreme head was also acknowledged among all peoples south of the river Humber; from what is now Lincolnshire to the Middle and the East Anglians, to the border peoples of Cheshire, Shropshire, and Hereford, to the men who dwelt about the Severn, to the Angles of Kent, to the Saxons of the east, the middle, the south, and the west. London itself was a Mercian city.

Such was still the position of Wessex when Egbert, Alfreds grandfather, came to its throne. The history of his coming holds interest for us. Sixteen years before this time, in 786, he had laid claim to this throne as one of direct descent in the royal House of Wessex as well as a prince of Kent. His claim was strong. But it had met a stronger force. In this same year of 786 the crown of Wessex was gained by one named Beorhtric, a man of obscure ancestry but fortunate in the support of Offa himself, king of Mercia and overlord of Wessex. Offa had sealed this alliance in 789 by giving to Beorhtric his daughter, Eadburh, in marriage. Promptly Egbert fled from England to find refuge among the Franks at the court of Charles the Great, and Beorhtric remained king of Wessex for these sixteen years.

In 802 Beorhtric suddenly died. The manner of his dying, strange and violent, if we may believe the gossip down the years of West Country tradition, brings King Alfred into our story. Long afterward Alfred told all that he himself had heard about it to his friend and counselor, Asser of Wales, and we still have Assers reporting of the tale. Alfred told, and Asser must have hung upon his words, that the Lady Eadburh, after her marriage to Beorhtric, had become so haughty and overbearing toward her husband at the Wessex court that she did everything in her power to injure anyone for whom he cared. She also accused of evil in his presence all who had in any way offended her, hoping to deprive them of influence or even of life. If her efforts failed, men declared, she slipped poison into their drink; and one day her husband, King Beorhtric, drank by mistake of the cup which she had poisoned for another and so came to his end.