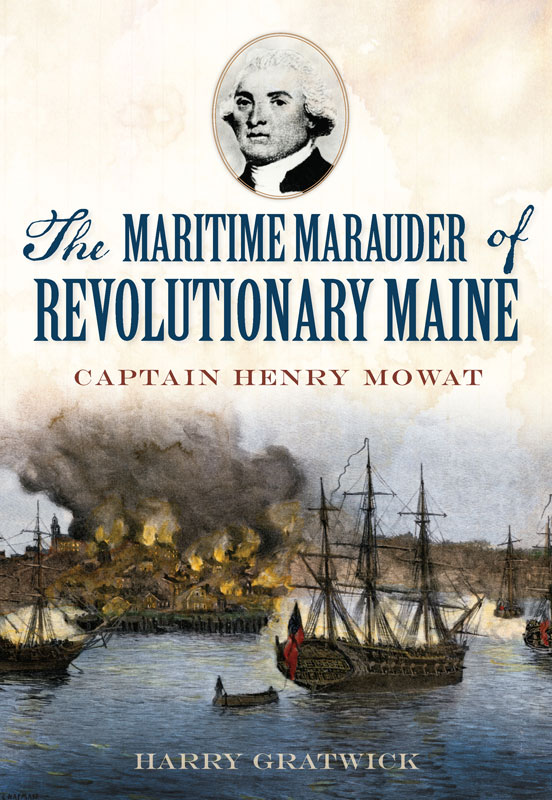

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Harry Gratwick

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.053.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955493

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.518.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to Captain John Flint, a resident of Cushing, Maine, who died in 2013. Without his encouragement and support the book would not have been possible.

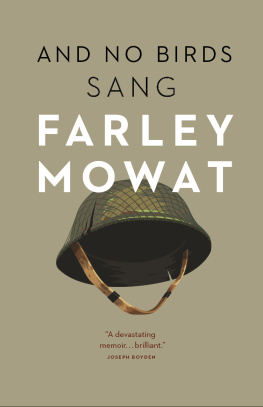

The author is indebted to John Flint for sharing his research on the life of Henry Mowat. Authors collection.

THE MOWAT CONTROVERSY

An outrage exceeding in Barbarity & Cruelty every hostile Act practiced among civilized nations.

George Washington, when informed of the burning of Falmouth Neck (Portland).

Was Henry Mowat a vengeful miscreant, or a duty-bound naval officer operating within a narrow range of choice? Either way, his role in the history of Revolutionary Maine is significant.

Louis Arthur Norton, professor emeritus, University of Connecticut.

An execrable scoundrel, infamous incendiary and monster of ingratitude.

Reverend Samuel Dean, pastor, First Parish Church, Portland, Maine.

It is sufficient for us to say that Henry Mowat ruthlessly and needlessly destroyed a thriving and well ordered town peopled with men and women of his own race scattered them abroad exposed to suffering and death form want hardship and exposure.

James Phinney Baxter, mayor of Portland and Maine historian.

His name lives to be execrated, and his dark deeds are portrayed to teach base men, what indelible infamy shall cleave to their memories.

William D. Williamson, nineteenth century Maine politician and historian.

No objective historian would attribute ultimate responsibility for the destruction of Hiroshima to the crew of the Enola Gay. Likewise, Lieutenant Mowat as commander of the flotilla had orders, which he carried out.

William Barry, archivist, Maine Historical Society.

Contents

Foreword

Harry Gratwicks insightful, beautifully rendered portrait of British naval officer Henry Mowat gives us for the first time a clear picture of one of the more important but, until now, dimly understood figures in Americas early history. On October 18, 1775, Mowat was the commanding officer of a four-ship squadron that, without provocation, conducted a massive bombardment of Falmouth (now Portland), Maine, wreaking havoc on its citizens, destroying their city and forcing them to flee from their homes just as winter was approaching.

Reaction to what can only be described, even from the perspective of 240 years, as a shocking war crime was instantaneous. The merciless destruction of the most important seaport in the Maine District of Massachusetts spread horror and anger throughout America, uniting the thirteen colonies as never before. Calls for independence multiplied, making the sacrifices necessary to fight the greatest military power of the age much easier to make. More than ever, Americans were determined not to become second-class citizens in an empire dominated by a small elite of landed aristocrats who could inflict such atrocities from three thousand miles away.

On hearing of the extreme reaction to the pitiless treatment of Falmouth, wiser heads in London soon realized that Mowats raid was counterproductive, and they quickly distanced themselves from him and his superior in Boston, Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, claiming they had gone too far. But, as Harry Gratwick deftly explains, this was not the case. Mowat was carrying out a policy that the hardliners who ruled Britain had been advocating for months, indeed years. A few smart blows, they believed, would frighten provincials into submission. Graves and Mowat were simply following the dictates of their superiors.

Regardless of who was ultimately responsible, however, Graves and Mowat became convenient scapegoats. Mowat suffered the most because he had a long career. No matter how well he performed his dutiesand by any measure he performed them well, as Harry Gratwick showsMowats contemporaries were promoted while he languished in the same rank year after year. Understandably, he became bitter. But American patriots, who knew nothing of his difficulties, would have been pleased to learn of his treatment by the very people who were responsible for the orders that got him into trouble. Working up sympathy for the man who had destroyed Falmouth and inflicted so much pain in pursuit of a military strategy that had the exact opposite effect from the one intended was impossible.

George Daughan was the recipient of the 2008 Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature for his book If By Sea.

Acknowledgements

Writing a book about an obscure eighteenth-century British sea captain presented a number of challenges, not the least of which was to locate sufficient sources dealing with his career. In addition to John Flint, I would like to thank the following people for their encouragement in helping me research the life of Henry Mowat: Linda Hall at the Williams College Library; Desire Butterfield-Nagy, archivist and special collections librarian at the Fogler Library, University of MaineOrono; Gail Judge at Public Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Paige Lilly at the Castine Historical Society; Bill Barry, Sofia Yauloris and Nicholas Noyes at the Maine Historical Society, Portland, Maine; Terry Cole Ranger at Fort Point State Park; and Nina Coffin, graduate assistant at LaSalle University.

In addition, I am grateful to historians George Daughan, Jim Leamon and Charles Bracelen Flood for their suggestions in my pursuit of the often-elusive life of Henry Mowat.

Finally, a salute to my wife, Tita, for her editorial expertise, her love and her cheerful support.

Introduction

Henry Mowat was descended from a family of Scottish seafarers. Legend has it that one of his ancestors was a nobleman who survived the Spanish Armada and settled on the Orkney Islands, which is where Henry was born. This makes a good story, though there is compelling evidence that the founder of the Mowat clan in England was a member of the 1066 Norman Conquest whose descendants later moved to Scotland.

William Barry, archivist at the Maine Historical Society, likens Mowat to C.S. Foresters fictitious British naval hero Horatio Hornblower. Both men were capable and daring Royal Navy officers whose actions were often handicapped by unimaginative, plodding superiors. The chief difference between the two was that, unlike the successful and well-connected Hornblower, Mowats career was long and mostly undistinguished. As we shall see, it was also highly controversial.

![Farley Mowat - People of the Deer [Paperback]](/uploads/posts/book/52958/thumbs/farley-mowat-people-of-the-deer-paperback.jpg)