For

John S. Monagan

and

Morton S. Jaffe

Craftsmen of the Law

Keepers of the Flame

Preface

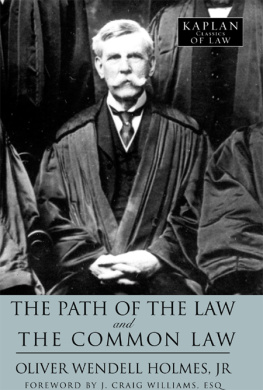

In 1921, William Howard Taft became Chief Justice of The United States. One of his fellow justices, a veteran of nearly twenty years on the bench, was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Despite differences in judging the law the two became good friends, whose mutual esteem was one of the features of the 1920s court. For both men their justiceships were the capstones of their careers in public service from which they gained immediate personal satisfaction as well as national acclaim.

Historians and biographers have yet to treat Taft and Holmes as cut from the same bolt of cloth. Ordinarily, Taft is remembered as both a judicial conservative and a court activist. For his part, Holmes has been celebrated as a court liberal and an advocate of judicial restraint. Such characterizations are accurate enough, as far as they go. Taft, however, gave clear indications that legal realism had a place in American jurisprudence, and from time to time Holmes was heard to speak in less than liberal tones.

This study delivers more than its title appears to promise, yet the title remains appropriate. It is an account not only of the decade of their common court membership but an explanation as well how Taft and Holmes arrived at the summit of their public vocations. It reveals their common heritage and traces their divergence in jurisprudential matters. They derived from like backgrounds in family and fortune and grew to manhood when scientific materialism was the persuasive philosophy. It was as knights-errant they entered the legal lists, bent on doing justice. Yet in the fulness of their years there had emerged two justices and two different meanings which they gave to the great law, the Constitution.

What was it about themnatural or instinctive, studied or acquiredthat denied them a common philosophy of the law? And, when evidence can be advanced to explain their diversity, were Taft and Holmes merely representive of the variations common to individual reactions to and interpretations of the intellectual forces at work in society? Or were they competing symbols for the spirit of an age?

The method employed to get at these and other questions is dual quasi-biographical. Much biographical detail is presumed. Life experiences are treated to the extent necessary to convey comparative and contrasting elements in their growth and development, in their thought and work. Take, for example, their educational careers at Yale and Harvard, making allowances for the sixteen years' difference in their ages. Or again, consider the early Washington days when they were important men in the capital of the emerging American colossus. Can Taft's entry into political life offer some indication of his later judicial opinions, in contrast to Holmes's sequestered years on the high court?

There are paths to follow, friendships to be evaluated (including their own), and writings to be examined as their lives resembled one another, running on parallel but widely divided lines that finally merged in the 1920s court. There a final contest between opposing visions took place, one with unanticipated results. Analysis of their work on the 1920s court, building up from the early chapters, promises to render the results more understandable.

In prefacing this study, it is important to note that Taft and Holmes are treated as important men of the law, and beyond that, as equally important public servants. Although Holmes was senior in age, Taft had attained the two highest offices provided in the Constitution. By reference to formalities, Taft, as president and later as chief justice, outranked Holmes by a goodly measure. In contrast, Holmes enjoys the greater historical reputation without impugning Taft's ability as a legal thinker. By cutting across the grainin other words, by writing about Taft and Holmes rather than Holmes and Taft, and given the aim of this study (namely, an analysis of the 1920s court, a Taft court)I am asking the reader to put aside the image of Holmes as the grand panjandrum of the law. In fact, to do so requires little more than reading history and biography forward, not backward, always the best way to proceed. The pertinence of this caveat is made more explicit by pointing out in the year Taft was Solicitor General of the United States, Holmes was best known for his scholarly book, The Common Law, not for his interpretations of the Constitution of the United States. Or again, when Holmes was a member of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, William Howard Taft was serving as a federal circuit court judge in Ohio. The reader must be reminded of such considerations to explain, if not to justify, the emphases that obtain in approaching Taft, Holmes and the 1920s court.

Both individuals and institutions merit thanks for helping me in the research and writing of this book. Saint Joseph's University has extended support in various ways and the Earhart Foundation provided a generous and timely grant, thereby aiding in the completion of the work. My colleague, Professor Graham Lee, has been a wise counselor and generous friend to the project from its very inception. Chris Dixon of the staff of Drexel Library, Saint Joseph's University, has been a ready and reliable source of advice and help. I allow the dedication of this volume to speak to the role played by two esteemed men of letters and the law.

Introduction

At the midpoint of the nineteenth century, the American mind was basically traditional. The values that society honored and lived by looked mostly to the past. This was the intellectual and moral milieu into which William Howard Taft and Oliver Wendell Holmes were born. If their own particular home environment was not as typical as the conventions of the time dictated nevertheless the larger world in which they were to move, and take exception to, must be identified and grounded in inherited and long-maintained principles. Taft and Holmes were of that generation which was to challenge old ways of thinking and acting as they helped in singular fashion to recast the American outlook. Because the changes brought about by the scientific revolution were not all-inclusive, because there occurred a synthesis in which old ideas were wedded to new ideas to produce new truth, some account of the nature of those old ideas is appropriate. By touching on American religion and philosophy, law and government, and economic theory and practice, the adaptations made by both Taft and Holmes may be more readily understood.

A reminder of where America stood in 1850 is my purpose in this introduction. The most critical development in American thought in the last third of the nineteenth century, the formative decades for Taft and Holmes as men of the law, was that supernaturalism was undercut by new findings in the physical and natural sciences. The dramatic and seemingly irresistible triumph of science is warrant enough to direct attention to the traditional elements that were carried forward into the next century. Such ideas, evident in the legal philosophies of Taft and Holmes, would influence many of their most important court opinions.