O ver five thousand years ago, a man braced himself against the bitter cold as he ascended a mountain in the Alps. He was badly hurt. An attack in the valley below had left him with a deep stab wound between the thumb and index finger of his right hand. Now he was far from home, at least one or two days walk through the ice and forest. This was not a journey for the faint of heartor for the unprepared. The man wore a coat, leggings, hat, shoes, backpack, and other attire that had been stitched together from the skins of several different animals. In a pouch on his belt he held stone tools for cutting, scraping, and boring, as well as chunks of pyrite he could strike to make fire. Threaded onto a leather strap were two chewy lumps of antiparasitic birch fungus fruituseful when youre suffering from whipworm. He had a copper axe, bow and arrows, and a dagger made of chert. The dagger had been painstakingly sharpened many times. He might need it. Was he being followed, even up here in the snow at the top of the mountain?

The mans frozen, mummified corpse was found in 1991 preserved in an Alpine glacier, surrounded by his extensive equipment. He came to be known as tzi, after the tztal Alps where he was found, or simply as the

The human mind is a virtual time machine. With it we can relive past events and imagine future situations, even if we have never experienced similar situations before. Humans do this incessantly, daydreaming about summer vacations, savoring the thought of upcoming dinner dates, and brooding over test results. Because humans are mental time travelers, we can prepare for opportunities and threats well in advance, as tzi did, trying to shape the future to our own design. Foresight, our ability to anticipate events and act accordingly, is perhaps the most powerful tool at our disposal. This book is about the nature and evolution of this ability and its role in the human story.

Of course, just because we can imagine the future does not mean we actually know what will happen. In the end, tzi probably didnt foresee the arrow that hit him in the back and put him on ice for five thousand years. Much of what comes to pass we do not anticipate, and much of what we anticipate does not come to pass. Even professionals specializing in prediction, such as stockbrokers and meteorologists, often struggle to forecast the price of gold next quarter or whether it will rain next Tuesday. Human foresight can fail spectacularly. You may have heard of backyard engineers attaching helium balloons or rockets to their chairs in eager anticipation of flight or speed but without adequate contemplation of how they might suddenly drop or stop.

Human history is littered with anecdotes of poor planning with catastrophic consequences, such as when Queensland government officials brought cane toads to Australia to kill the pesky cane beetle, only for the toads to reproduce out of control and ravage the local ecosystems. So this book is also about the many limits of human foresight, and how people deal with them.

Throughout history, humans have conjured up audacious strategies to help them peek ahead in time. An entire alphabets worth of fortune-telling methods abounds, from abacomancy, reading the future in dirt, sand, smoke, or ashes, to zoomancy, reading it from the behavior of birds, ants, goats, or asses. What these -mancies have in common, of course, is that they do not work as advertised. Nonetheless, they are among the many products of a fundamental human quest: to grapple with an uncertain future and figure out the best way forward.

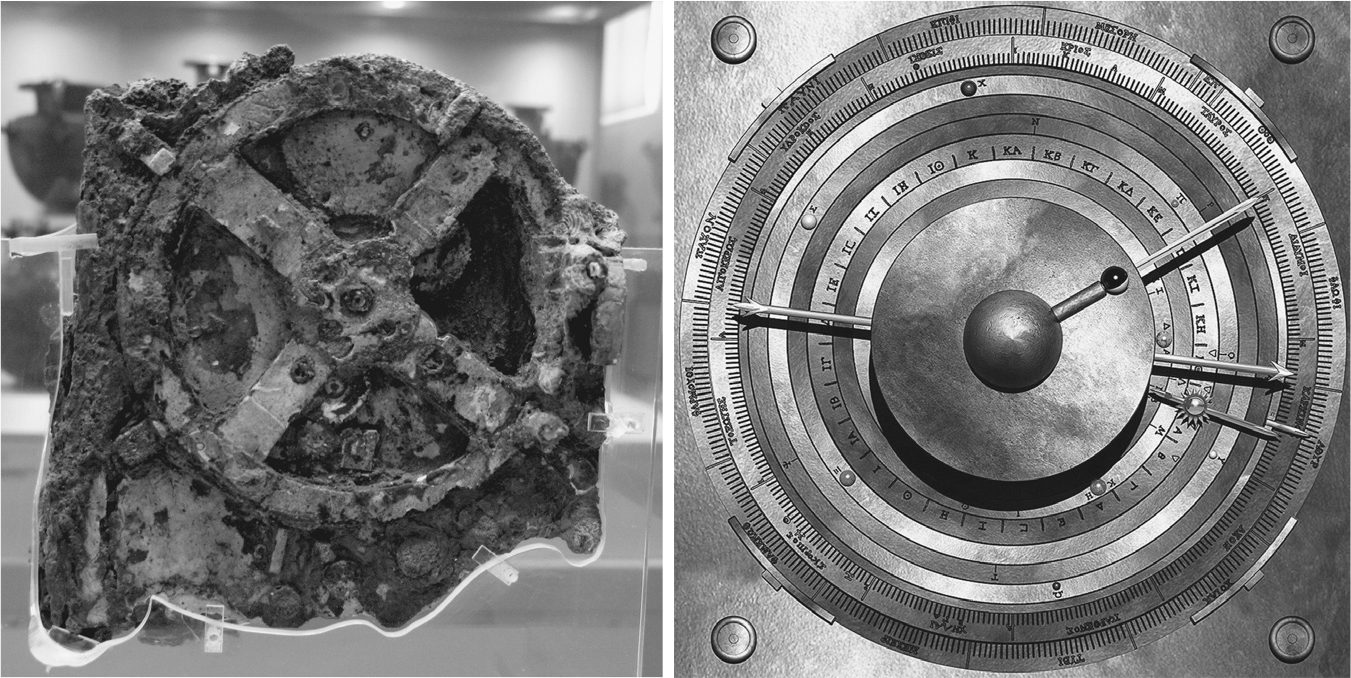

While the future cannot be found in entrails or tea leaves, there are some patterns in nature that can help us predict and prepare. The ancient Greeks, though they would routinely consult the oracle before embarking on a major venture, also created remarkably effective forecasting tools. A room in the Greek National Archaeological Museum in Athens is dedicated to one particularly enigmatic artifact used for this purpose. Pulled from the Aegean Sea in 1901 by sponge divers off the island of Antikythera, the unassuming lump of mangled wood and corroded metal would only many decades later be identified as the worlds earliest-known analog computer. It is over two thousand years old.

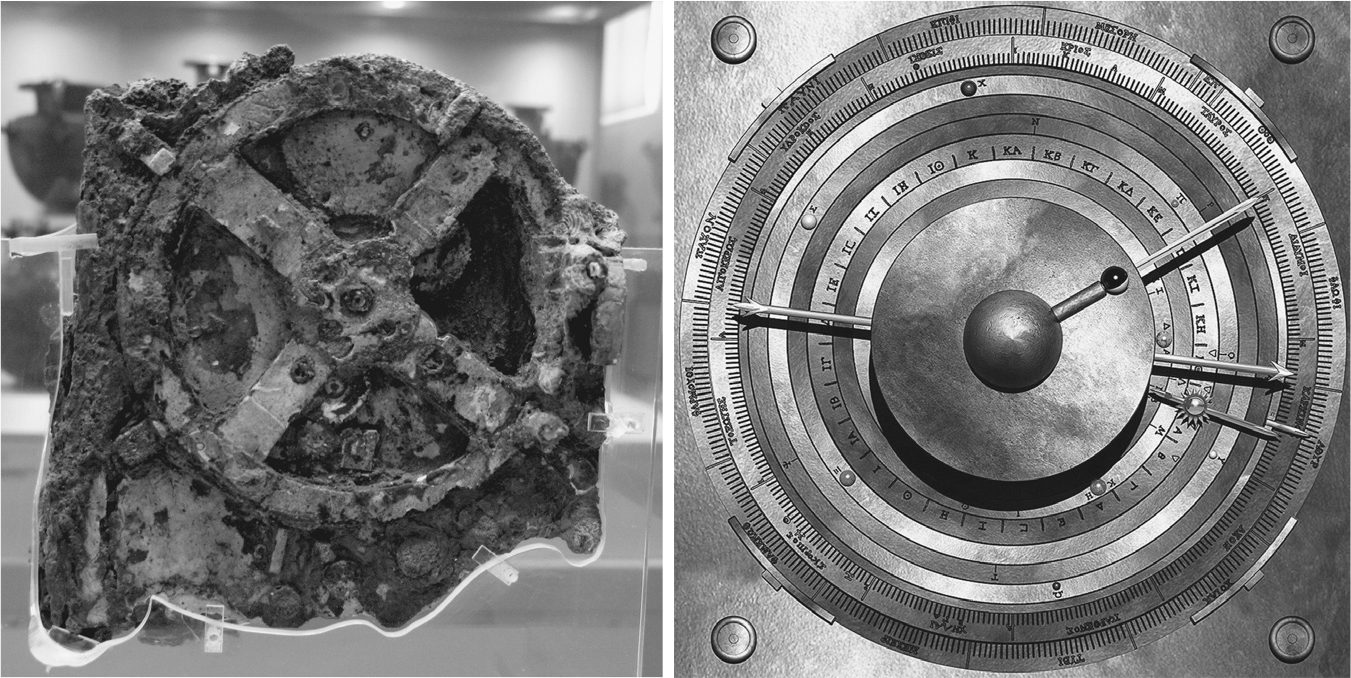

The Antikythera mechanism is a relic of astonishing technological complexity, featuring dozens of interlocking bronze gears and faded, arcane inscriptions. By turning a hand crank, its operator could select a calendar day on a front dial and predict the future of celestial bodies: the movement of the planets, phases of the moon, and eclipses of the sun. The Roman statesman Cicero enthused that by contemplating the predictable regularities of the heavens, the mind extracts the knowledge of the Gods.

Figure 1.1. The Antikythera mechanism as it looks today (left) and a model of what the cosmos display would have looked like (right).

Modern humans have extracted ever more knowledge about nature and how to predict its course. Though we might struggle to conduct any of the required calculations ourselves, today we can precisely forecast the time of high tide or the passage of celestial events by consulting devices that fit into our pockets. A quick look at Wikipedia tells us that Venus will transit the sun on March 27and Mercury will do the same a day laterin the year 224,508 AD. Closer to home, our everyday lives are increasingly built on shared schedules and models of the future that guide human cooperation. We clock into our nine-to-fives, meet for weekly book clubs, and toil towards important deadlines.