2018 by Joseph Tartakovsky

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

First American edition published in 2018 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

All images sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Tartakovsky, Joseph, 1981

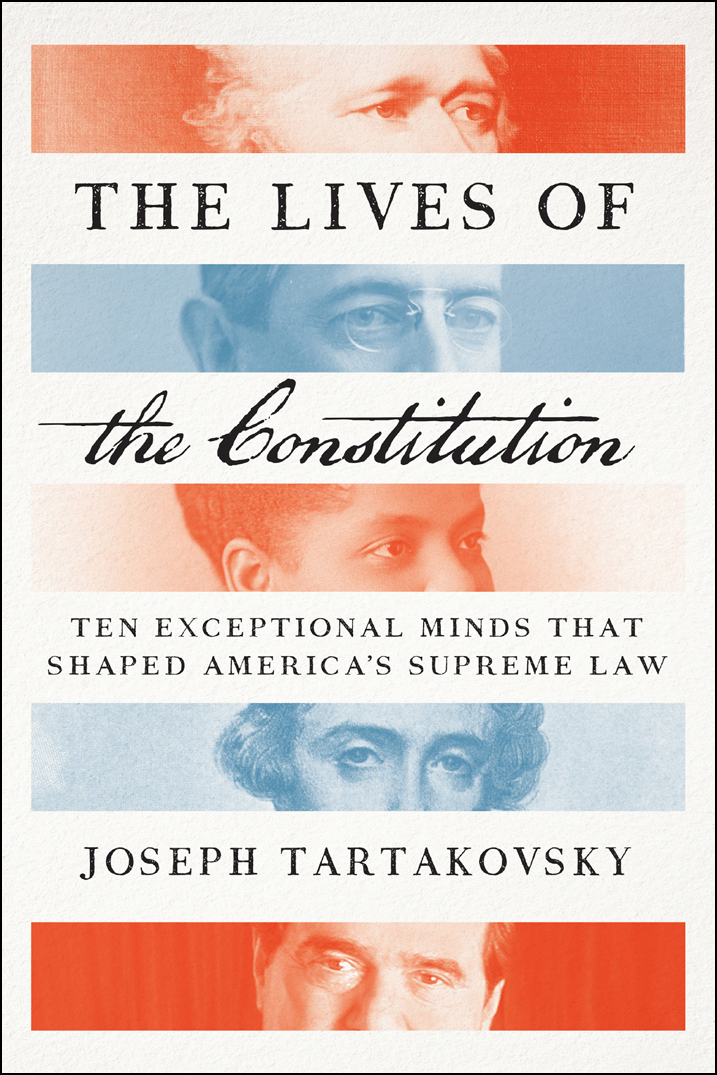

Title: The lives of the constitution: ten exceptional minds that shaped Americas supreme law / by Joseph Tartakovsky.

Description: New York: Encounter Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039034 (print) | LCCN 2017039283 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594039867 (Ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Constitutional lawUnited States. | Constitutional historyUnited States. | United States--Politics and governmentHistory.

Classification: LCC KF4550 (ebook) | LCC KF4550 .T37 2018 (print) | DDC 342.73--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039034

Interior page design and composition by BooksByBruce.com

To my parents,

Dr. Anita Friedman and Igor Tartakovsky,

who constituted me in every respect.

CONTENTS

Table of Contents

Guide

E very nation has a founding myth. The Bushmen of Africa claim they emerged from a hole in the earth; the Iroquois of America say they descended from a gap in the sky. The Romans had Romulus and Remus; the Israelites a covenant in the Sinai desert. Other foundings involve monsters, gods, floods, and planetary prodigies. The American story, then, at first glance, is not very promising: its a bunch of legal documents. Yet our tale has the compensating virtue of emerging not out of mysterious antiquity, but out of provable fact. We have something rarer even than the supernatural: the documentary record of a nation rationally created. We have it in our power to begin the world over again, wrote Thomas Paine, an early enthusiast for the task. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The Founding Fathers, the time-tested carpenters of our ark, were great enough for myths to gather around them. But the truth of our origin remains a matter of recollection, not imagination.

Americas greatest contribution to world civilization has been in the art of establishing and preserving free republican government. By now weve had the longest practice on earth. Our national regime has operated uninterrupted since 1789, through even a civil war. During that time, France, a country that, like us, makes bold claims about having lofted the banner of world liberty, has advanced from its First to its now Fifth Republic, with two Napoleonic empires, a monarchy, and a Vichy puppet regime in between. I think that the United States Constitution has endured, I should say right up front, because it is the finest ever written. It is terse enough to fold into a paper airplane. It is rigid enough to restrain excesses and flexible enough to accommodate innovations. And it is based on principles true in theory and workable in practice.

But the story of our Constitution cannot be told merely as an account of a legal charter. It must be told as a story of human beings. I try to follow, humbly, the biographical method of Plutarch on the Greeks and Romans, Samuel Johnson on the English poets, or Lytton Strachey on the Victorians, all of whom proved that you could best capture a civilization by following some of its prominent members in their adventures through it.

I chose ten individuals whose large thoughts and unafraid deeds all teach something crucial about the American Constitution. The first two figures in this book, Alexander Hamilton and James Wilson, began their services to the Constitution while it was still a glimmer in their far-sighted eyes. Hamilton, an island orphan, led the drive for a new Constitution, then breathed life into it as Washingtons most trusted advisor in its shaky first years. James Wilson was a Scottish immigrant whose blazing intellect made him a philosopher in thought and a colossus in debate at the Constitutions drafting and ratification in 1787 and 1788. The heavy-browed Daniel Webster defended the Constitution as a politician in the first generation to follow the framers, though the generation after him would wade through rivers of gore to vindicate the cause he championed.

Stephen Field, a Gold Rush lawyer who became a fiery Supreme Court Justice, presided in the heady days when postCivil War America first flexed its industrial might. I call in two Europeansboth lofty Viscounts, no less, in their peeragesto examine us and our Constitution in the searching way that only foreigners can: Alexis de Tocqueville, in the first half of the 19th century, and James Bryce, in the second. Woodrow Wilson, hard-driving and prolific, took the White House in 1912 at the height of a reordering of American law now called the Progressive Era. Ida Wells-Barnett was a one-woman army who fought a lonely moral and journalistic war against anti-black violence and misogyny between Reconstruction and the Jazz Age. Robert Jackson was a dapper and quite deadly lawyer who offered the most enduring defenses of President Franklin Delano Roosevelts crisis powers during the Great Depression and Second World War. And the late Antonin Scalia, son of a Sicilian immigrant, was a Supreme Court Justice whose feisty brilliance defined todays battle lines over the Constitution.

Each of them had a hand in conceiving, drafting, and ratifying the Constitution, or in interpreting, challenging, amending, preserving, or applying it to radically new conditions. They are linked to one another, and to us, by the fact that we, too, in our peculiar circumstances, continue to have the necessity and opportunity to make for ourselves a more perfect Union. There are crucial differences between the founding lawmakers and those who followed, but all ages require the same spirit. The historian Clinton Rossiter put this too perfectly to paraphrase:

The one clear intent of the Framers was that each generation of Americans should pursue its destiny as a community of free men. We honor them most faithfully, and do our best to make certain that other generations of free men will come after us, by cherishing the same spirit of constitutionalism that carried them through their history-making adventure. The spirit of the Framers was a blend of prudence and imagination, of caution and creativity, of principle and practicality, of idealism and realism about the governing and self-governing of men. In the constant regeneration of this spirit of 1787 in American public life rests the promise of a future in which our power is the servant of justice and our glory a reflection of moral grandeur.

![Blackstone Audio Inc. - The politically incorrect guide to the presidents: [from Wilson to Obama]](/uploads/posts/book/167736/thumbs/blackstone-audio-inc-the-politically-incorrect.jpg)