This edition published in 2011 by Arcturus Publishing Limited

26/27 Bickels Yard, 151153 Bermondsey Street,

London SE1 3HA

Copyright 2002 Arcturus Publishing Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN: 978-1-84858-431-0

AD000447EN

Edited by Paul Whittle

Cover and book design by Alex Ingr

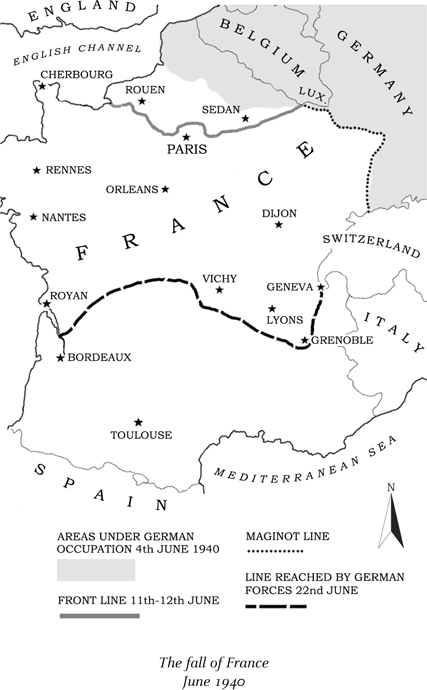

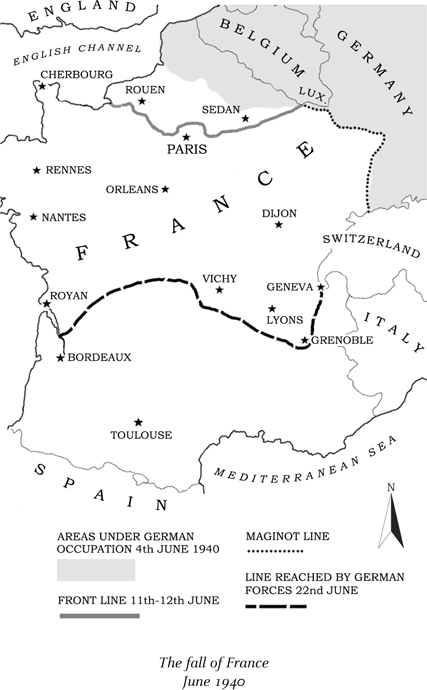

Maps by Alex Ingr and Simon Towey

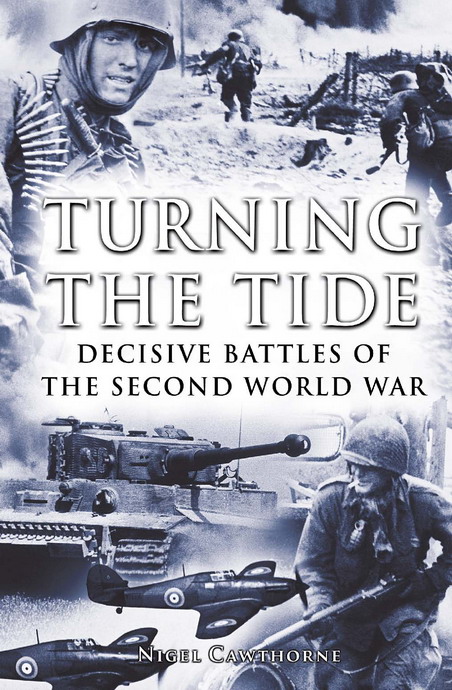

Cover images Robert Hunt Library

CONTENTS

A LTHOUGH THE SECOND WORLD WAR has been over for nearly 60 years and most of those who took part in it are no longer with us, the war remains a topic of enduring fascination. How was it that the world could be drawn into such madness, which consumed the lives of some fifteen million servicemen and women, and between twenty and forty-five million civilians? And how was it that the efficient and well-equipped armies of ruthless warlike states, who seemed initially unstoppable, could be defeated by a coalition of nations who had no desire to go to war?

The origins of the Second World War can be found in the First World War. As an ally of Britain, France and America, Italy had been on the winning side in 1918, but it did not do as well out of the peace settlement as it expected. In the period of economic instability that followed the war, the political agitator Benito Mussolini seized power. In 1922, he became the first Fascist dictator, promising his people a return to the glories of imperial Rome. His new empire did not stretch very far though. In 193536, he seized Abyssinia (now called Ethiopia) and in 1939 he occupied Albania.

After the First World War, many former members of the German army, including the Austrian corporal Adolf Hitler, were disaffected. They felt that they had been defeated not on the battlefield, but by Communist agitation at home, a feeling encouraged by the Dolchstoss legend (the 'stab-in-the-back'). Many prominent German Communists at that time were Jewish. Those who opposed them played on the long tradition of anti-Semitism in Germany. The $33 billion in reparations demanded by the victors in the First World War at the Versailles Conference of 1919 bankrupted Germany and brought political infighting to the streets. The result was the rise to power of the Nazi Party and its demagogic leader Adolf Hitler, who became Chancellor in 1933. In 1936, he signed an agreement with Mussolini, forming an anti-Communist 'Axis'.

Hitler made no secret of his ambitions. In his political manifesto, Mein Kampf ('My Struggle') published in two volumes in 1925 and 1927, he makes no attempt to hide his anti-Semitism. He also makes clear that he intends to make Germany a mighty empire on the Continent with its borders extending to include European Russia, where the Slav peoples would be dominated by the Teutonic master race.

Hitler made his first gains by diplomacy, arguing for the return of territory taken from Germany by the Versailles agreement. He got the Saarland back from France in 1935, reoccupied the Rhineland in 1936, against the advice of his generals, and took his native Austria into his Third Reich in 1938. (The First Reich or realm had been the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806; the Second Reich was the German Empire under the Prussian Hohenzollerns from 1871 to 1918.) After the Anschluss (joining) with Austria, Hitler demanded the Sudetenland, part of Czechoslovakia, and threatened war. A peace conference in Munich in September 1938 dismembered Czechoslovakia, giving Hitler the territory he wanted. In March 1939, however, he seized the rest of Czechoslovakia. What Hitler really wanted was to go to war. He had progressively defied the Versailles agreement that had also disarmed Germany. He rearmed and soon had a powerful army, air force and navy. The Western Allies, particularly Britain and France, had suffered huge losses in the First World War and they had no desire to go to war with Germany again. Their armed forces were ill-prepared for a modern war so they had little choice but to appease the demands of the dictator.

Japan had also been on the winning side in the First World War and, again, was disappointed in the territorial gains it was awarded in the peace settlement. However, the Versailles Conference awarded Japan former German concessions in China. The Japanese had long coveted an Empire like the ones Britain, France and the Netherlands had established in the Far East. In 1910, it had annexed Korea and, during the First World War, had established a toehold in Manchuria. In 1931, the Japanese consolidated their hold on Manchuria and, when the Chinese objected, fire-bombed Shanghai. The Chinese appealed to the League of Nations, which found in China's favour. Japan promptly withdrew from the League. When China was further weakened by the fall of the last Emperor of the Manchu Dynasty, Japan swallowed up Mongolia and parts of China's Hebei province.

Up until this time, the Japanese military had been constrained by a civilian government at home. But in 1936, the military seized power in Tokyo and signed the anti-Communist 'Axis' pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. In 1937, the Japanese commanders in Manchuria decided to 'solve the Chinese question once and for all' and launched a full-scale invasion. The United States insisted that Japan be 'quarantined' for this aggression.

On 23 August 1939, the staunchly anti-Communist Hitler signed a Non-Aggression Pact with the leader of the Soviet Union Communist Russia and its satellites Joseph Stalin. Everything was set for a war that would engulf the whole world.

Over the six years of war that followed, there were hundreds of battles. Unfortunately there is not the space to cover them all here. Indeed whole campaigns are missing, such as the heroic fight by British and Dominion troops against the Japanese in Burma. It has also not been possible to include such decisive action as the Battle of the Atlantic, which maintained the British lifeline from America against German submarines and warships, or the RAF and USAAF the United States Army Air Force, as the American air force was then known bombing campaign against Germany. But these actions went on day-after-day for years and are not battles in the conventional sense.

However, the decisive battles we have picked here do cover the main scenes of action. Taken together, they explain how the war progressed and how the use of improved technology, the harnessing of industrial might, the development of well co-ordinated combined operations and the willingness of individuals to sacrifice their own lives for what they thought to be right finally brought victory to the Allies.

THE ROAD TO DUNKIRK

THE SECOND WORLD WAR began on 1 September 1939. At dawn, a huge German army rolled across the 1,250-mile Polish border. Immediately Britain and France ordered a general mobilisation. Their ambassadors in Berlin delivered identical messages to the German Foreign Ministry saying that if Germany did not withdraw her troops from Poland, Britain and France would 'fulfil their obligations to Poland without hesitation'. France had had a military treaty with Poland since 1921 and Britain had pledged its assistance to Poland, if its independence was threatened, on 31 March 1939, marking an end to the policy of appeasement.

Next page