My thanks to my old friend Robin OConnor for his patience and research. It would have taken so much longer otherwise.

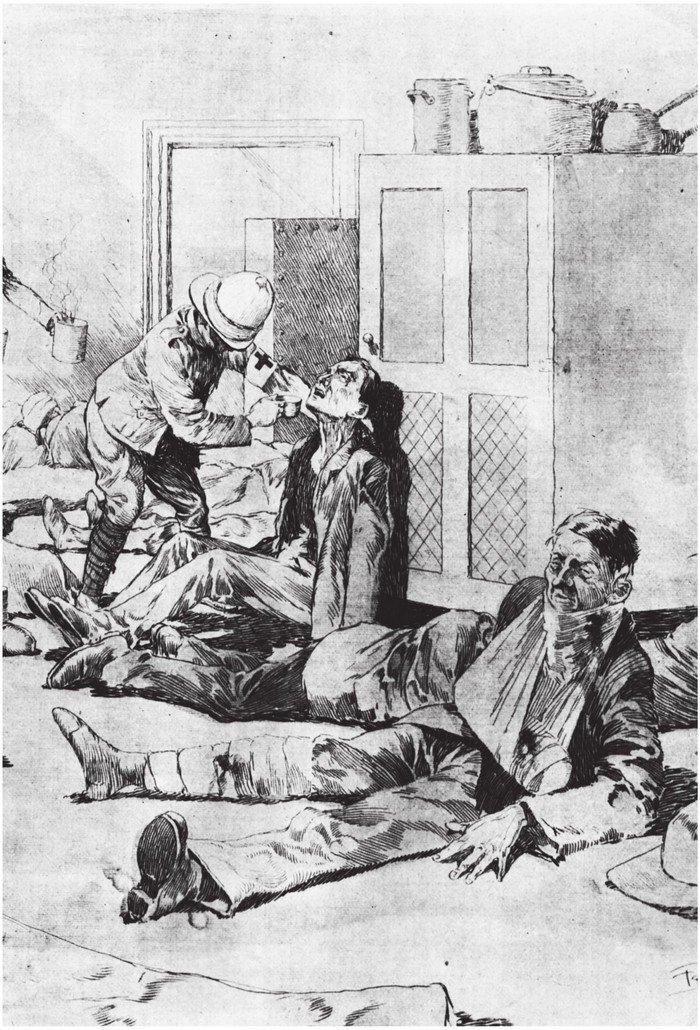

T his is a book about the trade, the art, the business of war reporting and some of its greatest practitioners. But as the title might suggest, it is not only about reporting war but the parallel war relentlessly waged against correspondents by those who would prefer, and even demand, that only their own versions of events are published: the military, the establishment and the many and various fighting factions.

From the Crimea and the Somme to Iraq and Afghanistan, war reporters fight on many fronts. It has always been so.

The war reporters I have chosen have no special placing in the league of the Greats. They are simply my favourites, paragons if you like. You probably have your own listing.

I went to my first war, or rather it came to me, when I was only three years old. My family lived in Essex, about three miles from the Thames, which meant we were directly under the Luftwaffes nightly bombing runs into the London docks. Our nights were spent in an underground Anderson shelter at the bottom of the garden, dank and smelly and lit by a single paraffin lamp when there was paraffin, and by a single candle when there was not. My mother would sing Bing Crosbys You Are My Sunshine and pause and hold a finger to her lips as we listened to the distant explosions. When we dared, which was not often, we would peek out to see the orange pink of fires over London and the criss-crossing beams of searchlights, like immaculate white marble columns, as they probed the blackness for the invaders. In the park, less than half a mile away, the ack-ack guns, the anti-aircraft batteries, followed their beams, hoping to hit something all those thousands of feet up.

My mornings were spent with the other boys in the street collecting bomb shrapnel and shell splinters and, just the once, a jagged piece of grey-painted aluminium, part of a German bomber that had been hit by our guns. I still have it. One morning, as my mother was hanging out her washing, a Dornier flew over so low I swear I saw the Luftwaffe Iron Crosses on its wings.

In between, we children went to war with our little lead toy soldiers, the British painted khaki, fighting the enemy in grey, the garden our battlefield. Mounds of earth became our mini-fortresses as entire battalions were slaughtered. We Brits always won; that was the rule.

Then, like thousands of other children from the cities of Britain, I was suddenly without a home or a mother. That autumn morning in 1940 she took me to Paddington station, settled me in the carriage of my first train and tied a manila label around my neck with my name and registration number scrawled on it. With my gas mask on my lap and jam sandwiches in my jacket pocket, she left me without a hug or kiss goodbye. I saw only the back of her as she hurried away sprayed by the locomotives steam; a mother, like so many, returning to an empty Anderson shelter and the lonely nights of fear, sans children, sans husband, sans everything. None of us cried. I seem to remember only laughter. We must have thought we were simply off on holiday.

I was an evacuee on my way to a farm in Somerset, one of the youngest in Operation Pied Piper, and it would be three years before I saw my mother again.

Many of us were returned home before the war ended and, for some, it was too soon. The bombing was less frequent but we were not safe, night or day. The air raid sirens were not silenced. In 1944 the Germans sent us something new, the V1 flying bomb; we nicknamed it the Doodlebug. We could hear it coming, a low growl, growing louder until it was overhead. Then, as the last of its rocket fuel was burnt, silence. We held our breath for a minute or more, praying. Would it drop like a stone and hit us or glide to end others lives? It was a hateful wait.

I remember our end of war street party, the commotion and the banter and the painted banners strung across the lamp-posts. I did not know then what the initials V.E. meant except that they were making everybody happy and drunk. Within a month my father came back but not for long. He was a major in the Royal Engineers and had been one of the first to land in Normandy. Now he was part of what was called the C.C.G., the Control Commission of Germany, and he was in charge of repairing and regenerating a section of the DortmundEms Canal. When he returned to Germany in the winter of 1946 we went with him, the first British family to arrive in Emden, Westphalia.

A nine-year-old English boy was suddenly in the country of the people who only six months before had been the feared and hated enemy. In the years that followed, he saw things that are indelible and remain the most prominent in a grown mans lockerful of memories. Emden, a city the size of Leicester or Canterbury, flattened by Allied bombing from horizon to horizon, so that not one building stood intact. That winter, the survivors lived among the ruins, the more fortunate in their cellars. There were makeshift crosses in the rubble and every so often, along the verges of the country roads, an upturned rifle, the barrel dug into the ground with a German helmet on the butt, which marked a soldiers shallow grave; signposts of the dead.

One day, my father was supervising the exhumation of the British dead who had been hastily buried in a mass grave. I cannot remember why I was with him; we must have been en route to somewhere else. He forbade me to leave the car but a small boys curiosity edged me closer to a place to watch. It was the smell that overwhelmed me and I vomited then and for some days afterwards. The doctor said it was mild dysentery but my father knew it was not.

My boarding school, Prince Rupert in Wilhelmshaven for the children of servicemen, had been a training base for U-boat officers . The Royal Air Force had attacked and sunk every submarine in their pens and at lunchtimes we schoolboys, quite nonchalantly, watched Royal Navy divers, in their brass helmets and lead boots, bring up the bodies of those who had been trapped for so long inside their metal coffins.

A few childhood memories of war.

And war has remained with me all my life. Exactly thirty years ago, at the end of that very bloody conflict, I left the Falklands and did not expect ever to return.

I should have known better. How many times in over forty years of a reporting career have I said that about so many places only to be contradicted by events.

Returning to a war zone is the oddest mix of excitement and sadness, and I have been back to many. But nostalgia can be a very assorted package and in the Falklands it is especially so.

All the other wars I have covered have been wars in foreign places, other peoples wars. But in 1982, in those ten weeks of a Falklands spring, I was reporting a war among my own people, British soldiers fighting on behalf of those who were defiantly, obstinately, British.

Last Christmas I went back to the Islands to take part in an ITV documentary to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the war. I found them in good health and booming and not at all fussed by the distant sound of rattling sabres.