ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS:

HISTORY OF CHINA

Volume 3

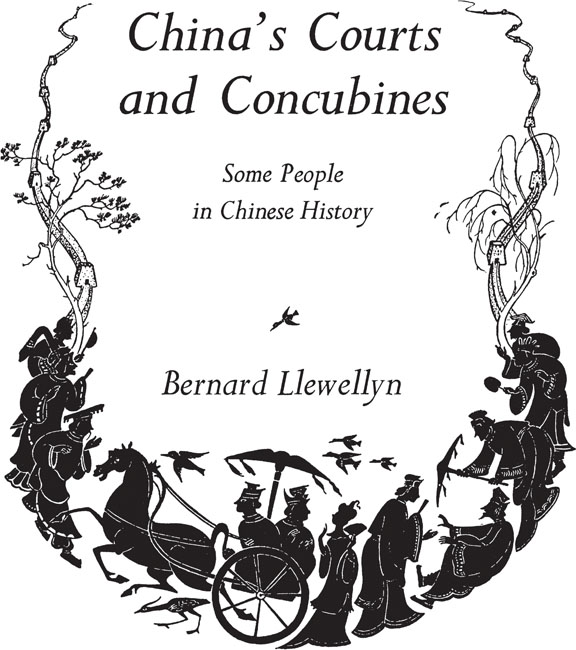

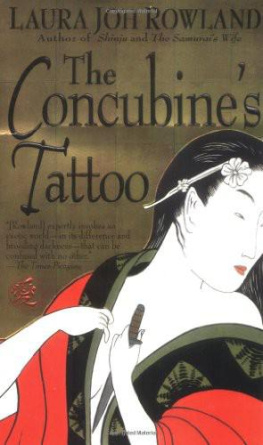

CHINAS COURTS

AND CONCUBINES

CHINAS COURTS

AND CONCUBINES

Some People in Chinese History

BERNARD LLEWELLYN

First published in 1956 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1956 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-48273-9 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-45536-0 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-57999-6 (Volume 3) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-46402-7 (Volume 3) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Illustrated by Pauline Diana Baynes

LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD

CONTENTS

First published in 1956

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1911, no portion may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiry should be made to the publishers

Printed in Great Britain

in 13 point Perpetua type

by Simson Shand Ltd.

London, Hertford and Harlow

NO one can write a book of this kind without being conscious of the great debt he owes to the research and scholarship of many men and women. Often their work lies neglected on the shelves of our great libraries gathering the dust; but it is there. And because it is there, others can use it for their own purposes.

No sinologue who may chance to turn over these pages will have any doubtespecially if he looks at the Notes and Sources at the end of the bookthat this volume is not for him. These potted biographies have no academic pretensions. Indeed, I hesitated at first to include references lest it should seem to the ordinary reader that I was aspiring to a scholarship I do not possess. But since I owe every scrap of this material to the patient researches of so many people, I thought it better to take the risk of appearing a little pretentious and make my obligations to others quite clear. Thus I have gathered together the references at the end of the book. There they will not bother the reader who is not interested in such matters; while they may encourage others to dig for themselves in these rich mines of history and legend.

To all the authors and publishers whose joint labours have put me in their debt, I offer my grateful thanks.

Thanks are also due to the editors and publishers of Everybodys, Eastern World, Chamberss Journal and The Malayan Monthly in whose pages I first told some of these stories; and to my friend John Cowan who, during my absence in the Far East, agreed to undertake the preparation of the Index.

Shirley, Surrey BERNARD LLEWELLYN

WHEN Du Haldes The General History of China appeared in four volumes before the British public in 1736, the translator felt able to make a bold statement in his Preface. After reviewing the extraordinary Precautions taken by the author to check his facts, he went on to say that the Publick may rest satisfied that what is here advanced is strictly true, which cannot be said of anything of this kind that has been hitherto publishd.

I wish I could repeat such brave words here, and assure my readers that everything they read in the following pages is strictly true. The men and women whose lives are written of in this book were real people: that much is certain. It is the details of their lives that may be disputed now and again.

Most of them lived so long ago that the events which made up their lives are buried as deep below the rubble of the years as were the walls of Troy beneath the earth at Hissarlik. That past is gone for ever. We cannot resurrect it to look at it again with our own eyes. We can only try to remember it; and inevitably, in that process of remembering, peoplesome of whom are far more credulous than othersrecall different things. It is true of our own past. How much truer is it of Chinas past!

It is the stuff of other peoples memories that makes up these pages. I cannot swear that their memories have never played them tricks when my own has failed me more than once. Thus you will read of magicians and immortals; of dragons and pills of eternal life; of generals and eunuchs; of emperors and poets; of palaces and concubines. And some of you who do not like the limits of the possible to range too far from the familiar and everyday may feel that occasionally truth has taken flight into the realms of fancy. It may be so. Who am I to decide such grave issues?

All I will say is that I have made nothing up. If there are liars along the route, they were there before I came along. If I mislead now and again it is without malice, and without much hope of doing better.

Of some of the people I have tried to bring to life for a little while in these pages many conflicting accounts have been written. Fact and legend have grown up together on the friendliest terms and, though I am no sinologue, I think it useless to pretend that the truth can ever be known in any detail at all. Over half the people mentioned here lived and died before Harold lost his eye and his life on the field at Senlac.

Rumours, stories, ballads, play-cycles, novels have not ceased to embroider the bare accounts in the old records. Let the scholars dig and probe as they will, the raw materials on which they must work can never, after all these years, be made the foundation for the kind of certainty some people demand. Even, as we shall see, those final decades of the nineteenth century are clothed in so much obsurity that, had I felt so inclined, I could have given the Grand Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi a character with which she would have been better pleased.

Such a word of warning is only fair to the reader who wants to know exactly where he stands. All colourful history and biography is an interpretation, nothing more. We try to interpret events so that they become intelligible to us. The Confucian scholars used the past as a mirror to reflect the vices and virtues of their own times. The lives of notable men and women were used to illustrate the lessons taught by the great sages. Who can doubt that sometimes the lives of the good were embellished still more, and the lives of the wicked painted blacker than they were?