PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

The Concubines Children

DENISE CHONG, an internationally published and award-winning author, has straddled two worlds: writing and public service. Of her books, she is best known for The Concubines Children, a Globe and Mail bestseller for ninety-three weeks. The first non-fiction narrative of a Chinese family in Canada, it has been translated into a dozen languages, most recently, almost twenty years after its first publication, into Chinese. In 2004, Chongs stage adaptation, produced by TheatreOne, premiered in Nanaimo, B.C. A two-time finalist for the Governor Generals Literary Award, she has published three other works of narrative non-fiction, which all depict equally groundbreaking social histories.

Trained as an economist, Chong began her writing life after an early career in the federal Department of Finance. She went on to become senior economic advisor in the office of then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. She was forty years old when she published The Concubines Children. She continues to pursue her interest in public policy, having served on task forces on issues ranging from the modernization of the public service to the Canadian cultural presence on the internet and in her capacity as co-chair of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada. Recognized for writing books that raise our social consciousness, Chong holds four honorary doctorates, was awarded the Queens Jubilee Medal, and is an officer of the Order of Canada. Her speech Being Canadian is widely anthologized. Born in Vancouver and raised in Prince George, she is married and has two grown children. She lives in Ottawa.

Trained as a medical doctor, TESS GERRITSEN built a second career as a thriller writer. Her twenty-four novels include the Rizzoli and Isles crime series, on which the television show Rizzoli & Isles is based. Among her titles are The Surgeon, Ice Cold, The Silent Girl, and Last to Die. Her books have been translated into thirty-seven languages, and more than twenty-five million copies have been sold. Gerritsen lives in Maine.

Also by Denise Chong

The Penguin Anthology of Stories by Canadian Women (editor)

The Girl in the Picture

Egg on Mao

Lives of the Family

DENISE CHONG

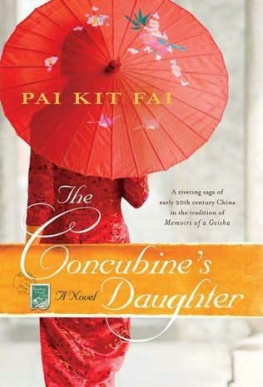

The Concubines Children

THE STORY OF A FAMILY LIVING

ON TWO SIDES OF THE GLOBE

With an Introduction by Tess Gerritsen

To the memory of my Dad

Introduction

by Tess Gerritsen

When I was a child, my family would sometimes drive up the coast from San Diego to San Francisco to visit relatives and to shop and dine in Chinatown. Id walk wide-eyed down Grant Avenue, marveling at grocery store tanks teeming with live fish and feeling overwhelmed by the crowded streets, the bright colors, and the noisy chatter of Cantonese. But amid all that bustling activity, one poignant image still haunts me: the groups of elderly Chinese men sitting in the park, playing board games. Why are there only men and no women? I asked my father. And he said, They came here a long time ago, but Chinese women couldnt come into the country, so those men could never marry or have children. Now theyre just waiting to die.

I was too young to understand how such a tragedy could have happened. I did not yet know the sad and painful history of Chinese immigrants in North America. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of Chinese men came to the United States and Canada, the vast majority of them laborers. In Canada, they came to build the Canadian Pacific Railway and later worked in mines, fish canneries, and lumber mills. In the U.S., they toiled in laundries and mines, and were 80 percent of the workforce that built the Central Pacific Railroad. By 1870, Chinese made up 9 percent of the California population and 25 percent of its workforce.

Perhaps worst of all, they were denied one of the most basic of human rights: the chance to marry and have children. The U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 shut out new immigrants from China, cutting off the entry of potential wives. With a male-to-female ratio of 26:1, Chinese men in America were doomed to live out their lives alone in grim boarding houses. They would go to their graves forgotten, condemned to an eternity in obscurity.

North of the border, similar sad stories were playing out in Canadian Chinatowns. In 1923, Canada passed the Chinese Immigration Act, its own version of the U.S. Exclusion Act. Families were often forever divided. While Chinese-Canadian men were permitted to leave Canada to visit China with restrictions on re-entry, many died without ever traveling home or being allowed to live with their wives or raise their children. For these lonely men, Chinatowns must have been sad places indeed, where the mere sight of a woman would have been a reminder of the heartbreaking void in their lives.

It is in this setting where much of Denise Chongs book The Concubines Children takes place. This luminous retelling of her familys multi-generational history is a journey through time and place and culture, from the farming village of Chang Gar Bin in south China to the Canadian city of Vancouver, from the poverty of China to the prosperity of Gold Mountain, from despised immigrants to successful citizens. Told with moving and intimate detail, The Concubines Children vividly brings to life the Chinatown of Ms. Chongs grandparents generation and the seemingly insurmountable challenges they faced.

The concubine of the title, the beautiful May-ying, travels to Canada using another womans Canadian birth certificate to join Chan Sam, a man whom she has never met. Though charming and resourceful, she is also willful and short-tempered and sometimes cruel, and as she slips into alcoholism, she causes no end of misery for their dutiful daughter, Hing. But May-ying is no villain; she is a far more complex woman than even her own family realizes. In searching for the real May-ying, Ms. Chong reveals a courageous and ultimately tragic heroine on whose small but sturdy shoulders rests the burden of keeping her family alive.

At the same time as Ms. Chongs family was setting down roots in Canada, my own family was on a similar journey in the U.S. My paternal grandparents also traced their origins to south China. After arriving in the U.S., my grandfather delivered newspapers and labored in restaurants, eventually owning a restaurant of his own on the San Diego waterfront. My father worked two jobs, as a restaurant cook in the evening and as an aircraft contract estimator during the day. My brother and I both became physicians. Like May-yings family in Canada, we too went from laborers to professionals in three generations.

So did Chinese families across North America. Recent statistics show that Chinese Americans and Chinese Canadians are now a prosperous ethnic group. In the U.S., they have one of the highest educational attainment levels and median household incomes of any racial demographic in the country. In Canada, they have entered Canadian universities in such impressive numbers that they now represent 25 percent or more of graduates from top universitiesin a country where they are only 4 percent of the population. To all appearances, ethnic Chinese have left behind their Chinatown struggles and achieved the North American dream.

While cultural respect for hard work and higher education is certainly part of the reason for their success, for Chinese in the U.S., it took a shocking historic event to accelerate their ascent. The bombing of Pearl Harbor and the entry of the U.S. into World War II led to tragic injustices against Japanese Americans, but for Chinese Americans, it opened a new era of possibility. Suddenly China was viewed as Americas ally against a common enemy, Japan, and Chinese Americans hastened to declare their allegiance to their adopted country. In 1943, the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed, opening the doors to a new surge of immigration. (In Canada, the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed in 1947.) But these new Chinese immigrants were unlike the desperately poor men who had arrived decades earlier to take the most menial of jobs. The recent arrivals included students, scholars, and businessmen from Hong Kong and Taiwan, and this brain drain of Asias educated elite to North America transformed the image of the Chinese immigrant. No longer were Chinese considered inferior coolies; now they were thought of as the smart kids in class, the computer nerds, the scientists and doctors and engineers. Based on the evidence of their economic success, one might conclude that ethnic Chinese have been fully accepted into American and Canadian society.

Next page