ALSO BY STEPHANIE WILLIAMS

Hongkong Bank: The Building of

Norman Fosters Masterpiece

Docklands

Copyright 2005 Stephanie Williams

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Williams, Stephanie, 1948

Olgas story : three continents, two world wars and revolution : one womans

epic journey through the 20th century / Stephanie Williams.

eISBN: 978-0-385-67346-4

1. Edney, Olga, 19001974. 2. RefugeesRussiaBiography.

3. RefugeesChinaBiography. 4. World War, 19391945Biography.

5. Soviet UnionHistoryRevolution, 19171921Biography. I. Title.

D413.E35W54 2005 909.82092 C2005-901223-4

Excerpt by Osip Mandelstam from Osip Mandelstam: 50 Poems. Translated by Bernard Meares. Translation copyright 1977 by Bernard Meares. Reprinted by permission of Persea Books, Inc., New York.

Excerpt by Anna Akhmatova from The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova. Edited and translated by Judith Hemschemeyer. First published in 1993 in Great Britain by Canongate Books Ltd., High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE.

Permission for worldwide photo publication of Kyakhta and Troitskosavsk ca. 1891 granted by the Archive of the Russian Geographical Society, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Fur skins at Irbot Fair by permission of the British Library, YA.2001.A.7732.

Any photos not otherwise credited are from the authors collection.

Published in Canada by

Doubleday Canada, a division of

Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limiteds website: www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For my family

in England, America, Canada, and Russia

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Place Names

This story is set in a vanished world. One of my greatest difficulties in getting started on my research was that virtually every place name mentioned in the text has since been changed. The name of Troitskosavsk, where Olga grew up, was abolished in 1934, and the town became subsumed into Kyakhta. Cathedral Street, where the Yunter family lived, is now Moscow Street. Verkhneudinsk is now known as Ulan-Ude, the capital of the Independent Republic of Buryatia. Russian Turkestan is now Kazakhstan.

Place names in Mongolia were changed after the Soviet takeover in 1922. Urga, the capital, became Ulan Bator. Today Mai-mai chen is Altan Bulag.

In China, I have used the British Post Office system of transliteration used in Olgas time. In Pinyin today, Peking is known as Beijing; Tientsin as Tianjin. Other less obvious changes to place names are indicated in the text.

Dates

Until February 1, 1918, Russia followed the Julian calendar of the Russian Orthodox Church, thirteen days behind the Western Gregorian calendar. All dates until February 1, 1918, are therefore according to the old Julian calendar. Thus, until 1918, Olgas birthday is given as July 10; afterward as July 23.

Measurements

1 verst equals 1.06 kilometers or 0.6 of a mile.

The population of Troitskosavsk/Kyakhta in 1917 was about eleven thousand. The names of some minor characters have been changed.

Give me your hands, listen carefully.

I am warning you: Go away.

And let me not know where you are.

Anna Akhmatova,

St. Petersburg, August 1921

some

stamp coins with lions,

others

with heads;

All kinds of copper, bronze and gold wafers,

Equally honoured, lie in the earth.

The age has tried to chew them and left

on each the clench of its teeth.

Time clips me like a coin,

And there isnt enough of me left for myself.

Osip Mandehtam,

Moscow, 1923

CONTENTS

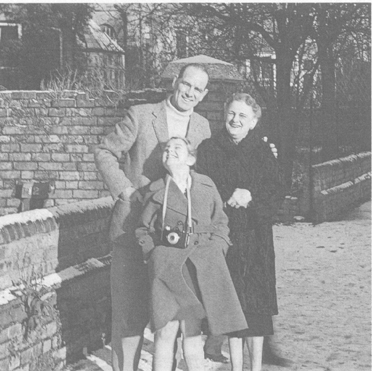

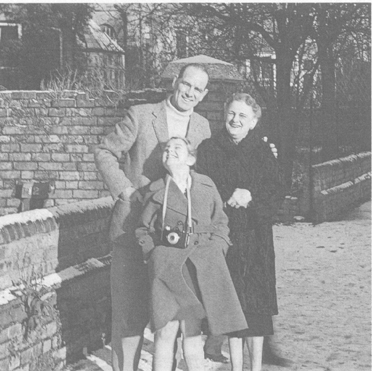

The author with Olga and Fred, Oxford, 1958

PROLOGUE

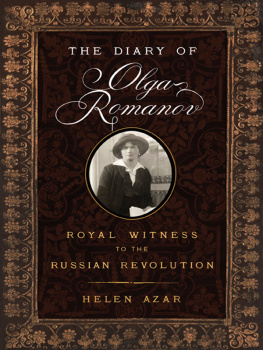

I used to have a picture of my grandmother taken in Shanghai in 1939. Olga is standing on a stage in mens evening clothes, telling jokes, one hand on her hip, the other holding a long cigarette holder, one foot raised and resting on a stool. With her thick, dark hair and tiny frame, she looked faintly exotic, Spanish perhaps, and sounded, with her deeply accented English, even more so to my young ears.

Olga loved people, loved to joke and gossip with good company. She had too much of a sense of humor to be described as grand. Yet when I was growing up she had a formidable presence. There was an invisible cordon, like a ring fence around her, as if she was aware of playing a part in some kind of higher agenda, one that was somehow beyond the rest of us. There was a sense that things were not in her power, that fate was in control. This gave her an air of authority, a confidence in her own judgment, a certain imperiousness.

Her aura served to reinforce the myths about her. Olga Yunter was the youngest child of a large family, a household with an assortment of servants, ranging from a superstitious peasant housekeeper to a bodyguard of Cossacks. She talked of attending a girls gymnasium; of going to the park, the cathedral, the opera, and the theater; of rarely sitting down to a meal with fewer than a dozen around the table. She had beautiful manners, spoke French and English fluently, and was widely read. A Russian migr of fine family, we thought. Wealthy, cultured, and well connected. Yet she came from Siberia.

She used to talk about Irkutsk, the capital of Siberia, far to the east of the Urals, its French architecture and its fine wooden houses, its cultured and sophisticated society. It sounded grand. She also talked about Kyakhta. There we pictured a small country estatelike those of other Russian migrswhere she would spend the summers, picnicking in the shade of a riverbank, playing games of lawn tennis and croquet, taking tea around the samovar under the birch trees while peasants harvested rolling fields of grain. We imagined Olga and her sister in starched white dresses like the daughters of the last Emperor, her brothers going hunting, wild troika rides across the snow in winter.

In fact, we knew virtually nothing concrete about her. We knew that her brothers had fought in the service of the Tsar; that her older sister had been educated in St. Petersburg. We knew that her family had been caught up in the Russian Civil War, that her brothers had been on the wrong side of the Russian Revolution as White Guard officers, and that she had made a dramatic escape from Russia into China. We suspected also that she still had reason to fear for her life, fifty years later, while living safely in England. These were the headlines. What lay behind them was a mystery.

![Sophie Law [Sophie Law] - Olga’s Egg](/uploads/posts/book/141435/thumbs/sophie-law-sophie-law-olga-s-egg.jpg)