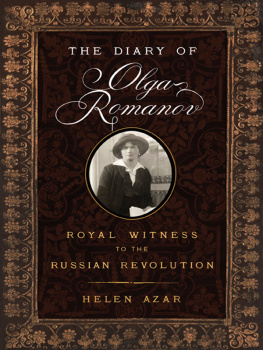

The Empress of Russia and Queen Alexandra

The Empress of Russia and Queen Alexandra

RUSSIAN MEMORIES

BY

MADAME OLGA NOVIKOFF

"O.K."

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

STEPHEN GRAHAM

AND FIFTEEN

ILLUSTRATIONS

HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED

12 ARUNDEL PLACE HAYMARKET

LONDON S.W. MCMXVII

WILLIAM BRENDON AND SON, LTD., PRINTERS, PLYMOUTH, ENGLAND

INTRODUCTION

BY STEPHEN GRAHAM

It is perhaps a little superfluous for one of my years to write an introduction for one so well known and so much esteemed and admired as Madame Novikoff. And yet it may seem just, if it does not seem vain, that a full-hearted tribute should come to her from this generation which profits by the result of her life and her workthe great new friendship between England and Russia.

She is one of the most interesting women in European diplomatic circles. She is a picturesque personality, but more than that she is one who has really done a great deal in her life. You cannot say of her, as of so many brilliant women, "She was born, she was admired, she passed!" Destiny used her to accomplish great ends.

For many in our society life, she stood for Russia, was Russia. For the poor people of England Russia was represented by the filth of the Ghetto and the crimes of the so-called "political" refugees; for the middle classes who read Seton Merriman, Russia was a fantastic country of revolutionaries and bloodthirsty police; but fortunately the ruling and upper classes always have had some better vision, they have had the means of travel, they have seen real representative Russians in their midst. "They are barbarians, these Russians!" says someone to his friend. But the friend turns a deaf ear. "I happen to know one of them," says he.

A beautiful and clever woman always charms, whatever her nationality may be, and it is possible for her to make conquests that predicate nothing of the nation to which she belongs. That is true, and therein lay the true grace and genius of Madame Novikoff. She was not merely a clever and charming woman, she was Russia herself. Russia lent her charm. Thus her friends were drawn from serious and vital England.

Gladstone learned from her what Russia was. The great Liberal, the man who, whatever his virtues, and despite his high religious fervour, yet committed Liberalism to anti-clericalism and secularism, learned from her to pronounce the phrase, "Holy Russia." He esteemed her. With his whole spiritual nature he exalted her. She was his Beatrice, and to her more than to anyone in his life he brought flowers. Morley has somehow omitted this in his biography of Gladstone. Like so many intellectual Radicals he is afraid of idealism. But in truth the key to the more beautiful side of Gladstone's character might have been found in his relationship to Madame Novikoff. And possibly that friendship laid the real foundation of the understanding between the two nations.

Incidentally let me remark the growing friendliness towards Russia which is noticeable in the work of Carlyle at that time. A tendency towards friendship came thus into the air far back in the Victorian era.

Another most intimate friendship was that of Kinglake and Madame Novikoff, where again was real appreciation of a fine woman. Anthony Froude worshipped at the same shrine, and W. T. Stead with many another in whose heart and hand was the making of modern England.

A marvellously generous and unselfish nature, incapacity to be dull or feel dull or think that life is dulla delicious sense of the humorous, an ingenious mind, a courtliness, and with all this something of the goddess. She had a presence into which people came. And then she had a visible Russian soul. There was in her features that unfamiliar gleam which we are all pursuing now, through opera, literature and artthe Russian genius.

Madame Novikoff was useful to Russia, it has been reproachfully said. Yes, she was useful in promoting peace between the two Empires, she was worth an army in the field to Russia. Yes, and now it may be said she has been worth an army in the field to us.

When Stead went down on the Titanic one of the last of the great men who worshipped at her shrine had died. Be it remarked how great was Stead's faith in Russia, and especially in the Russia of the Tsar and the Church. And it is well to remember that Madame Novikoff belongs to orthodox Russia and has never had any sympathy whatever with revolutionary Russia. This has obtained for her not a few enemies. There are many Russians with strong political views, estimable but misguided men, who have issued in the past such harmful rubbish as Darkest Russia, journals and pamphlets wherein systematically everything to the discredit of the Tsar and his Government, every ugly scandal or enigmatical happening in Russian contemporary life was written up and then sent post free to our clergy, etc. To them Madame Novikoff is naturally distasteful. But as English people we ask, who has helped us to understand "Brightest Russia"the Russia in arms to-day? And the praise and the thanks are to her.

STEPHEN GRAHAM.

Moscow,

27th August, 1916.

EDITOR'S PREFACE

The late W. T. Stead in saying to Madame Novikoff, "When you die, what an obituary I will write of you," was paying her a great compliment; just as was Disraeli, although unconsciously, in referring to her as "the M.P. for Russia in England." With that consummate tact which never fails her, Madame Novikoff has evaded the compliment and justified the sarcasm. Disraeli might with justice have added that she was also "M.P. for England in Russia"; for if she has appeared pro-Russian in England, she has many times been reproached in Russia as pro-English.

Of few women have such contradictory things been said and written, things that clearly show the gradual change in the political barometer; but her most severe critics indirectly paid tribute to her remarkable personality by fearing the influence she possessed. In the dark days when Great Britain and Russia were thinking of each other only as potential antagonists, she was regarded in this country as a Russian agent, whose every action was a subject for suspicious speculation, a national danger, a syren whose object it was to entice British politicians from their allegiance. Wherever she went it was, according to public opinion, with some fell purpose in view. If she came to London for the simple purpose of improving her English, it meant to a certain section of the Press Russian "diplomatic activity." The Tsar was told by an English journalist that he ought to "be very proud of her," as she succeeded where "Russian papers, Ambassadors and Envoys failed"; another said that she was "worth an army of 100,000 men to her country"; a third that she was a "stormy petrel." She was, in fact, everything from a Russian agent to a national danger, everything in short but the one thing she professed to be, a Russian woman anxious for her country's peace and progress.

In Serbia there is a little village whose name commemorates the death of a Russian hero, Nicolas Kiref, Madame Novikoff's brother. In his death lay the seed of the Anglo-Russian Alliance. Distraught with grief, Madame Novikoff blamed Great Britain for her loss. She argued that, had this country refused to countenance the unspeakableness of the Turk in 1876, there would have been no atrocities, no Russian Volunteers, and no war. From that date she determined to do everything that lay in her power to bring about a better understanding between Great Britain and Russia. For years she has never relaxed her efforts, and she has lived to see what is perhaps the greatest monument ever erected by a sister to a brother's memorythe Anglo-Russian Alliance.

![Sophie Law [Sophie Law] - Olga’s Egg](/uploads/posts/book/141435/thumbs/sophie-law-sophie-law-olga-s-egg.jpg)