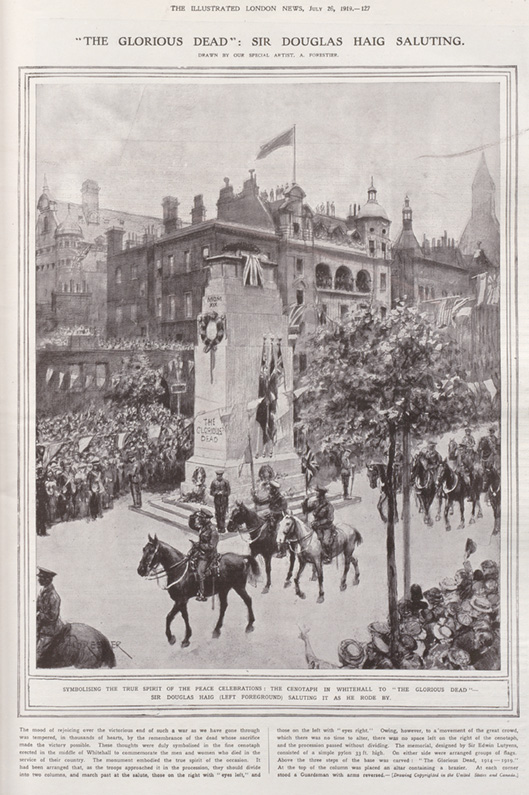

Like the Cenotaph, the empty tomb designed by Edwin Lutyens, a larger absent presence broods over the years between wars, the time aptly defined as the twenty-year truce: the fifty-one months and three days of severance, loss and bewildered suffering that, already in 1920, had been called the First World War. Any address, familial, local, national, must rest on some awareness of this massive collective bereavement, and the efforts to come to terms with it. Language stumbles; some broader avenue of purpose, longer and firmer, demands itself. Within and along words surfaces the idea of an older nature, shared within a visionary company, now yearned for through ideals and desires of the present.

The sheer physical nature of the Cenotaph, insistent in its emptiness, is just as revealing about patterns of idea, thought and belief. It is not its massive structure alone, or the presence or absence of inscriptions, its location, nor even its very existence. What makes it such a powerful entity is the way in which it melds together its use of language and its imposing visible form. That elements from each medium work for many without their being recognized in any way does not diminish them; we might just as well try to diagnose the power of great music or an ancient cathedral.

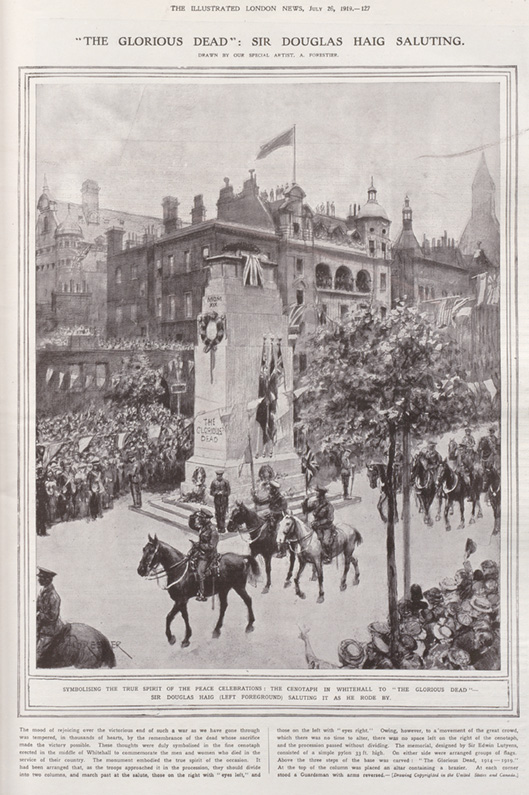

First constructed out of wood, intended as a temporary structure as part of the Peace Day parade on 19 July 1919 (), the Cenotaph instantly affected public opinion: after parliamentary debate, it was transformed into a permanent structure of Portland Stone. Like the original, its large vertical plinth reached its climax in a horizontal structure resembling a coffin. On two sides it bore the Union Flag and those of the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. Three stone wreaths were its only ornament: there was no cross or religious symbol. While at first glance defined by right angles, all of its seemingly straight lines are either curved or angled. The verticals have a batter, an architectural term for a rearward slant: their lines taper to meet at a thousand feet above ground. All the horizontals use an architectural principle known to the Greeks as entasis; they are very slightly convex, in an arc with a centre 900 feet below. The structures mass rests on regular patterns, the base of three equal cubes, the vertical form of three equal squares. Outlines give a sense of the organic, in place of something merely mechanical; the balanced masses suggest a rhythmic symmetry. The use of Portland Stone, one of the most commonly used English sculptural materials, and prominent in the buildings of Whitehall, adds a further sense of rightness. Like the use of local materials, a common practice in buildings of all kinds, it perpetuates a link between the land and its people. Perhaps, too, the thrusting verticals have a faint echo of the nineteenth-century ecclesiastical architect Augustus Pugins idea that church steeples should be as tall as possible, to manifest a yearning towards heaven. Their more immediate destination is the empty tomb itself; but beyond it there is a suggestion of something beyond words, but not beyond some sense of feeling.

Figure 1. The Cenotaph and the Victory Parade, 1919, Illustrated London News 26 July 1919. Via Humanities Library, University of Bergen

While these are physical elements of design, visual yet not visible, they are matched by the structures use of language. Where earlier memorials carry lengthy inscriptions, the Cenotaph has only three words: The Glorious Dead. With the absence of a cross, this avoids any particular belief, instead embracing all, and none. The image presented in the Illustrated London News included the words four times, once in the drawing itself and three times in the accompanying caption. Already, they have assumed the importance of a mantra, enshrined both in the monument itself and in accompanying discussions. Yet the words have a larger, unacknowledged and for many unrecognized, reference:

May the souls of the faithful departed rest in peace and rise again in glory.

The words, known as the Vestry Prayer, are traditionally spoken by the priest to the choir before processing into the church before many Church of England services. For generations, then and still, they are part of a ritual turned almost to an instinct: it is hard to believe that, for many at that time, even those of sorely tried belief, they did not resonate somehow in the words of the Cenotaph. Another ritual developed in the habit, begun soon after the Cenotaphs unveiling, for men to remove their hats when passing. At the centre of an irregular circle linking Downing Street, Whitehall, and Westminster, the Cenotaphs location is almost the pivot of the State itself, suggesting that death in battle is mourned by those in authority.

Few of these elements would be absorbed consciously. Instead, they are subsumed into larger feelings of impalpable loss, displacement, perhaps consolation, the rightness of memorial made physical through something seen, and made part of a longer process of mourning. In the coming together of word and structure, neither explicit yet each powerful through design and reference, something of great power has been made. This text is balanced in ritual by another: words from Laurence Binyons poem For the Fallen. First published in The Times in 1914, part of its text soon took on a larger function, ceremonial yet personal, when spoken in countless acts of remembrance and still used as such today. Priest, vicar, or celebrant would say the words At the going down of the sun, and in the morning/ We will remember them. The congregation would reply We will remember them. Their deep personal, as well as communal, resonance is shown in another text of word and image from the