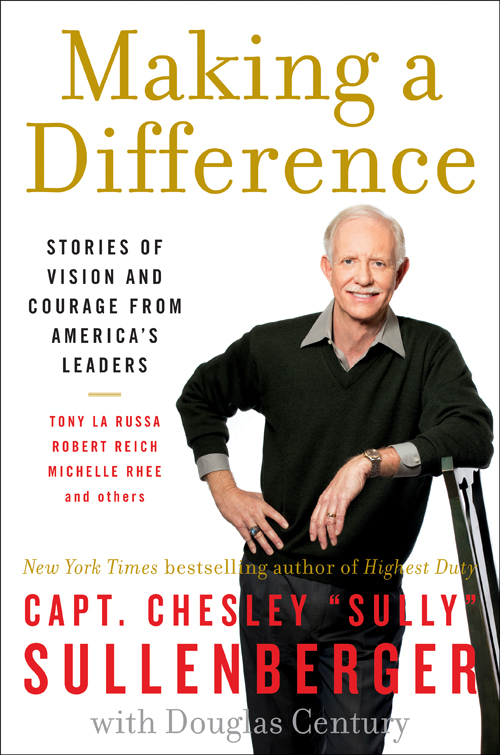

Making a Difference

Stories of Vision and Courage from Americas Leaders

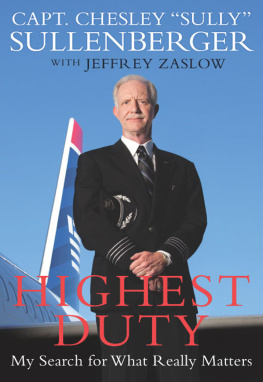

Captain Chesley Sully Sullenberger

with Douglas Century

To my wonderful wife, Lorrie, with love.

You are my inspiration.

Contents

A week after the Hudson River landing of U.S.Airways Flight 1549, on January 21, 2009, six people met in a governmentbuilding in the nations capital. The flight data recorder and cockpit voicerecorder (CVR) had just been recovered from the Airbus 320 and rushed to theNational Transportation Safety Board headquarters in Washington, D.C. There, inthe NTSBs sound lab, a windowless room with metal furniture and fluorescentlights, these six people gathered to listen to the CVR for the first time.

The cockpit recording of Flight 1549 has never beenreleased to the public. By law only the investigators and parties to theinvestigation may hear it. The only audio that has been released to the publicis the Federal Aviation Administrationss ground recording of the radiocommunications.

As these six peopletwo NTSB officials, an FAAofficial, a pilots union safety representative, and representatives from theaircraft manufacturer and the engine manufacturergathered in this closed roomin Washington, they did not know quite what to expect. All six wore headphones,concentrating intensely, often closing their eyes to better focus on everysound, every voice, in this dramatic recorded event.

My first officer, Jeff Skiles, and I had suddenlyfound ourselves in a crucible, fighting not only for the lives of our passengersand crew but also for our own. For three minutes and twenty-eight seconds thesix in the room heard two men working rapidly, urgently, and closely together.They heard a cacophony of automated alarms, alerts, warnings, synthetic voices,continuous repetitive chimes, ground proximity warning alerts, and trafficcollision avoidance system alerts, reaching a crescendo with TOO LOW, TERRAIN.TOO LOW, GEAR. CAUTION, TERRAIN. CAUTION, TERRAIN. TERRAIN, TERRAIN. PULL UP.PULL UP. PULL UP. PULL UP. PULL UP. PULL UP. PULL UP. PULL UP until therecording suddenly stopped.

The six were thunderstruck. They had never heardanything quite like this. They were overwhelmed by the suddenness, theintensity, the rapidity, and the severity of this 208-second-long event.

They sat in stunned silence until finally one ofthe six said, That guy has been training for this his entire life.

He was almost right. In fact, I believe my preparation for the events ofFlight 1549 began even before my birth. I would trace it back two moregenerations, to my grandparents, all four of whom were born in the nineteenthcentury; all four went to college, which was a remarkable thing, especially forwomen, at that time. My mother was a teacher, my father was a professional, andI grew up in an environment in which education was valued, in which ideas wereimportant, and in which striving for excellence was expected.

I was born in 1951, in the heart of the postwarbaby boom. My father, whod been a naval officer in World War II, returned fromhis tours of duty carrying oversize reference books filled with specifications,drawings, and armaments of ships from all the navies of the world.

I devoured those military books, as well as storiesabout men like Churchill and Eisenhower, those larger-than-life figures, culledfrom the copies of Life and Look magazines that my grandparents had lovingly collected duringthe war years. This idea of genuine leadershipofintense preparation, rising to the occasion, meeting a specific challenge,setting clear objectiveswas deeply internalized, burned into and ingrained inmy young mind....

I became a captain fairly rapidlyrelative to most airline pilots careers. After eight years with theairlinesstarting as second officer, then first officerI made captain. Thismeant I had a lot of timetwenty-two yearsleading a team, trying to inspirepeople every week, urging them to be vigilant and give their best efforts onevery flight. I observed the way even the most routine actions and the smallestwords could resonate and have an impact on the morale of a team. I saw that fewinteractions with my coworkers or the public went unnoticed or were completelywithout consequence.

Living ones life by the highest professionalstandards is one of the lessons I learned very early in my career. Id comestraight from the structured, disciplined environment of military aviation,specifically tactical aviation, where the margins for error are much slimmer andit is absolutely essential to strive for excellence daily. In the Air Force,when youre flying in a formation of four jet fighters, one hundred feet off theground, at six hundred knots, covering a nautical mile every six seconds, or tenmiles per minute, success and failure, life and death, can be measured inseconds and in feet.

In that kind of environment, where the higheststandards are taught and enforced, even the slightest deviation is immediatelycorrected because it is potentially catastrophic. In the airline world, thingsare slightly more complicated: there are many different life experiences,motivations, and concerns. Pilots meet the same professional standards; but ifthere are, say, a million ways to get from Point A to Point B, eight hundredthousand of them may be right. Or, I should say, rightenough. So there is a wide range of possible effective choices. Whilewe face many of the same risks as in military aviation, these risks may not seemas apparent.

I can describe what worked for me in my years as acaptain and team leader, but I saw many pilots doing good work, leadingeffective teams, with vastly different skill sets, personality types, andoutlooks.

I think most would agree that personal andprofessional reputations ultimately are based upon our daily actions andinteractions. For thirty years, I exercised vigilance and avoided complacency oneach flightbecause I never knew when, or even if, I might one day face someultimate challenge. Or, put another way, I never knew upon which three and ahalf minutes my entire career might be judged.

What does this mean in practice? How does thistranslate into other domains? Perhaps it means engaging in a lifelong commitmentto learning, to expanding ones mind, and to viewing each day as a cumulativeprocess of preparation.

This dedication to continuous preparation wasinvaluable to me during the events of Flight 1549. I had so deeply internalizedthe fundamental lessons that even in this novel and unanticipated situation, onefor which wed never specifically trained, I was able to set clear prioritiesbased on what we did know. In seconds, I managed to synthesize a lifetime ofexperience and training to solve a problem Id never seen before.

Given the rapid rate of change intodays culture and the constant state of flux in our industries, in oureconomic system, and in this worldwide marketplace of ideas, it is essentialthat we try to understand what it means to be an effective leader in the modernworld. For me, there is no effective way to cope with the ambiguity andcomplexity so prevalent today unless one has a clear set of values. But do allour leaders share this view?

Ive often felt that one of the most underratedaspects of leadership is the ability to create a shared sense of responsibilityfor the outcome: to inspire those around you to make tomorrow better than today,to constantly strive for excellence, and to refuse to accept anything thatsbarely adequate.

This means giving of oneself, rising to theoccasion, instilling a sense of group confidence that yes, together we canaccomplish what we might never achieve as individuals. It means setting thecourse, charting the path, giving your team the tools, encouraging them to dotheir best, then stepping aside and allowing them to accomplish the goal.

![Captain Chesley B. Sullenberger III - Sully [Movie Tie-In] UK: My Search for What Really Matters](/uploads/posts/book/404353/thumbs/captain-chesley-b-sullenberger-iii-sully-movie.jpg)