SI 81896

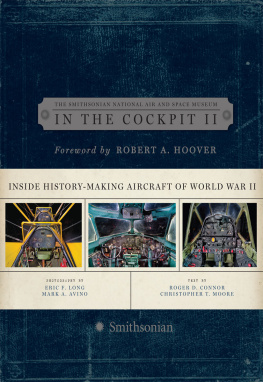

This book is dedicated to Donald S. Lopez* and those aircrew, ground crew, and engineers who supported the air war against the Axis tyrannies that threatened freedom in the terrifyingly tumultuous years from 1939 to 1945. The images presented here are a testament to the skill and fortitude of these extraordinary people and their opponents.

*Lieutenant Colonel Lopez (USAF, Ret.) was an ace with the Twenty-third Fighter Group, Fourteenth Air Force in China and served as deputy director of the National Air and Space Museum until his passing in 2008. He is sorely missed.

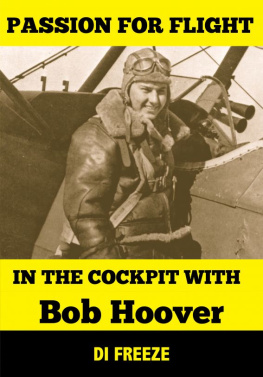

SI 200912321 Courtesy of R. A. Bob Hoover

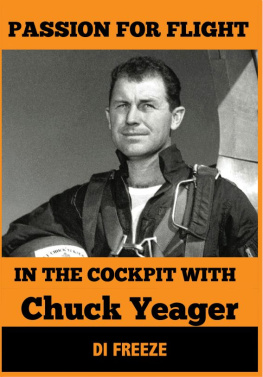

From the first storm clouds over Europe to the surrender of Japan, military cockpits saw dramatic improvements, yet by present-day comparisons they seem primitive. Having flown many of the planes depicted in this book, including most of the captured enemy aircraft, evaluating them on speed, altitude, range, and turning radius, I am often asked, Which was the best fighter over Europe?

This very same question was posed to a gathering of World War II fighter aces, and each pilot responded with the name of the aircraft type he flew in his Fighter Group. Colonel Hubert Hub Zemke, one of the most renowned P47 aces, was the last pilot to be questioned, and his remarks surprised everyone. He asked his fellow aces how many of them had been in combat in two or more types of fighter types. Only two responded. Hub then stated, Gentlemen, I have flown combat with all of your fighters and commanded each type of Fighter Group and I can assure you the P51, with its ideal balance of maneuverability, performance, firepower, and range, was the best of them all. This is my answer as well.

I wish to extend my appreciation to Gen. Jack Dailey (USMC, Ret.), Eric Long, Mark Avino, Chris Moore, and Roger Connor for this pictorial history of fading, but not forgotten, memories of yesteryear.

R OBERT A. B OB H OOVER

A s we enter our third book of cockpit interiors, we do so with large megabyte digital capture replacing large format film. This is due in part to the difficulty of getting film processed, the demise of Polaroid Instant proofing film, and to some degree, the difficulty of working with a film camera inside the cockpit. We advanced from shooting 4 x 5 films to working on the same Cambo Wide DS camera format, but adapted for a Phase One P-45 digital back, producing a 112 megabyte file size. The camera is supplied with a 24mm XL lens and center grade filter, giving the equivalent coverage of a 17mm lens on a 35mm camera.

Digital enabled us to view the image immediately on a laptop to check composition, lighting and focus. Due to the lack of a dedicated system, the camera and lens operated separately from the digital back, which needed a prestart before capturing an image. This required extra-long cabling attached to and from the computer and digital back and a cable release to the camera. The computer would not fire the camera, thus the shutter had to be manually cocked and fired. This could be accomplished by the person at the computer, or by someone inside the plane.

The digital files are shot in a RAW format. This allowed us the capabilities of working from one file to maintain shadow and highlight detail. It is to some degree like bracketing exposures on film. I prefer lighting as if we were shooting film, believing that digital manipulation should be a last resort. There are two downsides to digital. First, it is virtually impossible to enlarge a cropped area within a file to reproduction quality. Second, there is the issue of archiving the digital file. With film, it can be viewed years from now to determine what it is. With digital capture, it remains to be seen what media the image will be stored on and how it will eventually be viewed by future generations.

E RIC F. L ONG

PHOTOGRAPHER MARK A. AVINO, USING A LAPTOP TO CAPTURE THE EXPOSURE DIRECTLY FROM THE CAMERA, THEN CHECKS FOR DENSITY AND SHARPNESS.

SI 200931374

W orld War II occurred as aeronautical technology was undergoing a significant transformation. Though many new technologies, such as jet and rocket propulsion, radar, and helicopters were emerging before the outbreak of war, the unprecedented flow of government funds for research, development, testing, and production resulted in a dizzying transformation of the pilots environment in just a few years. The following pages reveal a wide range of complexity and ingenuity as seen on 34 aircraft operated by the major combatants during World War II. These aircraft reside today in the collection of the Smithsonians National Air and Space Museum. Some examples, such as the Aichi Seiran, have seen at least a decade of meticulous restoration to overcome the ravages of time. Others, such as the Bell Kingcobra, have weathered the years well with no intervention whatsoever. The Kyushu Shinden illustrates another group that is in desperate need of restoration and looks it. While several aircraft, like the Enola Gay , have been restored to a specific wartime moment (August 6, 1945), the Northrop Black Widow and Martin Mariner represent aircraft that continued their service well beyond the war years and whose cockpits reflect postwar modifications.

Many of the aircraft seen herein are on display, either at the Smithsonians flagship museum complex on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., or at the spectacular Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center located in Chantilly, Virginia. A number of the aircraft are in storage awaiting restoration at the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland. Several examples are on loan to other museums around the nation. These aircraft represent only a portion of the extensive World War II collection at the National Air and Space Museum. Some examples were excluded because of their inclusion in the previous volume of In the Cockpit or because of condition or lack of accessibility.

For many years, we have had the privilege to work around the exteriors of these aircraft. Preparing this book has given us a new appreciation for those who designed, built, and flew these incredible machines. We hope that beyond enjoying the sheer artistry of Eric and Marks photographs, you will come away with just a little more understanding of what it was like to fly in those turbulent times.

R OGER D. C ONNOR AND C HRISTOPHER T. M OORE

SI 2001127

S ituated half a world away from the United States, Japans geographic isolation influenced its war-fighting approach and led to the pursuit of unorthodox naval technologies, including a series of submarine-launched combat aircraft. The Seiran (Clear Sky Storm) was the final and most capable of these designs but was never used in combat. In the aftermath of the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo and subsequent losses during the Battle of Midway, the value of a submarine aircraft carrier with strike aircraft became more apparent. Japan already had extensive experience with submarine-launched aircraft, but in spite of a notable (if unsuccessful) 1942 bombing raid against the Oregon coast, these planes were designed for scouting, not bombing. By late 1942, the Aichi Company was developing the M6A1 as a true strike aircraft with a bomb or torpedo load of 800 kilograms. Accommodating several Seiran aircraft required construction of new submarines of unprecedented size. Work began on the I400 class submarine with a cruising range of 20,000 miles and the capacity to accommodate three M6A1s in a special 12-foot diameter watertight hangar tube. The similar I13 class could accommodate two Seirans.

Next page