BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Autobiographical

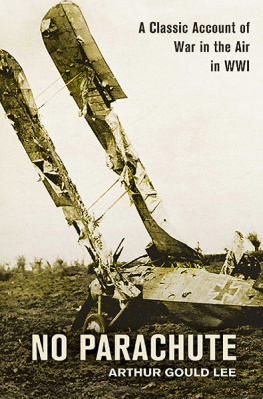

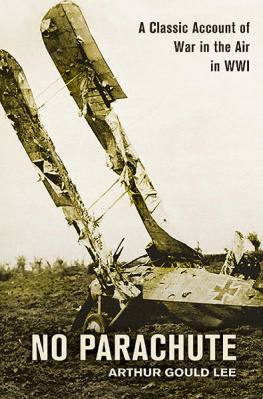

No Parachute: a fighter pilot in World War I

Special Duties in the Balkans and Near East

Biographical

The Flying Cathedral (Samuel Franklin Cody)

The Son of Leicester (Sir Robert Dudley)

Crown Against Sickle (King Michael of Rumania)

Helen, Queen Mother of Rumania

The Royal House of Greece

The Empress Frederick Writes to Sophie (LettersEdited)

Fiction

(under the pseudonym A. L. Gould)

An Airplane in the Arabian Nights

Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London SW11 6SS

First published 1969 by Jarrolds Publishers (London) Ltd

Arthur Gould Lee 1969

This edition first published 2012

Grub Street 2012

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Lee, Arthur Stanley Gould.

Open cockpit.

1. Lee, Arthur Stanley Gould. 2. World War, 1914-1918-

Aerial operations, British. 3. World War, 1914-1918-

Personal narratives, British.

I. Title

940.4'4941'092-dc23

ISBN-13: 9781908117250

EPUB ISBN: 9781909808836

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright

owner.

Cover design and book formatting by Sarah Driver

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall

Grub Street Publishing only uses FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper for its

books.

THE PUBLISHERWOULD PARTICULARLY LIKE TO THANK ANTHONY SAVELL

AND SAM GOWER FOR THEIR HELP IN BRINGING THIS PUBLICATION TO FRUITION.

CONTENTS

To David

my grandson

a subaltern of the Blues and Royals and a fledgling flyer too

One crowded hour of glorious life

Is worth an age without a name

Thomas O. Mordaunt 1791

AUTHORS NOTE

In my book No Parachute I described eight months flying in France on Sopwith Pups and Camels with No. 46 Fighter Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, from May 1917 to January 1918. Open Cockpit covers a longer period, from the time I learned to fly in 1916 until, my active service spell completed, I taught others to fly Camels up to and just after the end of the war.

The aeroplanes which I flew, additional to Pups and Camels, included the Maurice Farman and Avro on which I did my initial flying training, and the range of B.E.s on which I carried out the first phase of my so-called advanced training. All these machines were, by modern standards, about as primitive as bows and arrows. Not only were they fragile in constructionwooden, wire-braced frameworks and wings, covered with doped fabricbut rudimentary in their layout and equipment.

Every aeroplane of the day had an open cockpit in which one sat swathed in layers of woollen underclothing, fleece-lined leather great-coats and sheepskin thigh-boots, with which to resist the petrifying cold three or four miles up. There was no heating, no oxygen for high flying, no retractable undercarriage, no engine starter, no radio links with air or ground, no brakes to help with landing and taxiing, and, most vital of all, no parachutes. And there were no instruments worth the name. But we did carry a hammer to correct simple machine-gun stoppages!

Open Cockpit tells how the fighter pilots of the First World War flew and fought and instructed on these elementary early planes. So far as the chapters on combat flying are concerned, I have drawn on descriptions written on the spot at the time, mostly in letters. The sections on learning to fly, and on teaching others to fly, are recollections prompted largely by the entries in my flying log-books and other contemporary records.

Grateful acknowledgements are rendered to the following: Mr Gerald Austin of Jarrolds for his helpful promptings and suggestions during the planning of this book; Group Captain Guy M. Knocker for reawakening dormant memories of Joyce Green; and Mrs Frank R. Senn, of Florida, U.S.A., for alerting me to the active interest taken today in the United States in First World War aviation, and particularly in the knightly figure of Manfred von Richtofen.

I wish also to express my deep thanks to the following for their valuable assistance in providing me with some of the more notable photographs in this book: John Harris, G. Denham Jenkins, M. P. Marsh, H. A. Oxley, Alex Revell, L. A. Rogers, D. J. Stephens and W. J. (Jack) Wales; and particularly W. J. (Bill) Evans and Alex Imrie for their rare selection of in flight pictures of German World War I aircraft, and H. G. W. Debenham (the only flyer to serve in 46 Squadron first as an observer and later as a pilot) for his equally rare pictures of British 1917 aeroplanes in flight, with especial mention of the probably unique shot of a Nieuport under archie fire. I should add that to the best of my knowledge, these in flight photographs, as well as the majority of the others, have never been published previously.

Acknowledgement is also paid to the following publications which have been consulted for factual detail: The War in the Air, Vols iii and iv, by H. A. Jones, Sixty Squadron, R.A.F., by Group Captain A.J.L. Scott, C.B., M.C., A.F.E., and three of the Harleyford Publications.

Air Aces of the 191418 War, Fighter Aircraft of the 191418 War, and Richtofen and the Flying Circus.

A.G.L.

1969

FOREWORD

I brought the car to a halt, for I recognised the brick-built shrine, half smothered in ivy, that stood at the side of the track leading to Beaupr Farm, and to the encampment that had clustered by it during most of the First World War. The shrine, with its protecting glass-panelled doors, was a little dilapidated now, but someone had placed fresh flowers in a jar before the figure of the Virgin Mary.

Ahead of us should have been the line of canvas hangars backing on to the cobbled road that ran between La Gorgue and the larger town of Merville to the west, but they were no longer there. And the fields stretching north to the River Lys, that had once been our aerodrome, were now a vast plain of corn. In the burning July afternoon the heat shimmered over the flat expanse in quivering waves, just as it had done years before, in 1917, when I was young and a fledgling fighter pilot.

I turned the car off the road, and drove slowly towards the farm, a customary, one-story quadrilateral centred by a midden. The farm was exactly as I had known it in the past, even to the smell of the midden, but the wooden hutments had gone, save for a few of the largest, among them the long black-painted shed that had been the Officers Mess, and a smaller one which I had shared with three other pilots.

Nobody came from the farm to ask our business, for everyone was at work in the fields. Fifty yards in front of us was the line of poplars along the banks of the River Lys, or, as we usually called it, the canal, for such in fact it was, giving passage to giant barges, some under their own steam, some towed by horses on the towpath.

I left the car and walked to the bank of the river. And as I stood there, gazing at its turbid waters flowing sluggishly westwards, just as they had always done, nostalgia suddenly flooded over me. I closed my eyes, and out of the mists of time came voices long since stilled. I heard shouts and laughter, and the splashing of swimmers and divers, sounds that echoed here so many years ago. I heard again the voices of those who were to die within the year, sometimes of youngsters who frolicked in these waters only a few hours before they met their fate in the air.

Next page