Table of Contents

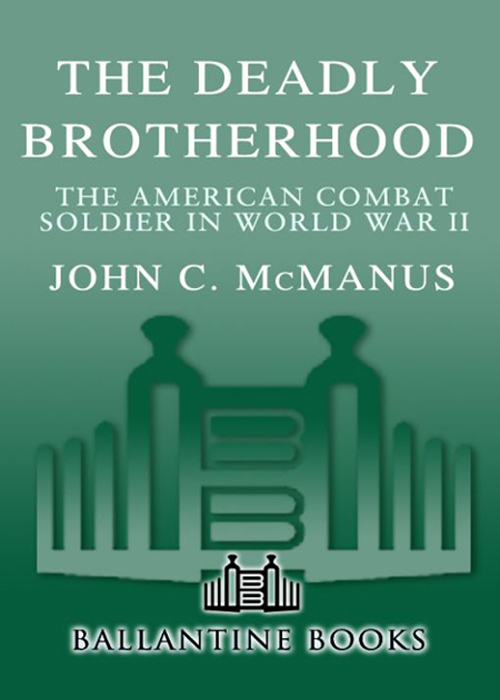

In his book Men Against Fire, [historian S. L. A.] Marshall asserted that only 15 to 25 percent of American soldiers ever fired their weapons in combat in World War II....

Shooting at the enemy made a man part of the team, or brotherhood. There were, of course, many times when soldiers did not want to shoot, such as at night when they did not want to give away a position or on reconnaissance patrols. But, in the main, no combat soldier in his right mind would have deliberately sought to go through the entire war without ever firing his weapon, not only because he would have been excluded from the brotherhood but also because it would have been detrimental to his own survival. One of [rifle company commander Harold] Leinbaughs NCOs summed it up best when discussing Marshall: Did the SOB think we clubbed the Germans to death?

Books published by The Random House Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000.

The rifleman fights without the promise of either reward or relief. Behind every river theres another hilland behind that hill, another river. After weeks or months in the line only a wound can offer him the comfort of safety, shelter and a bed. Those who are left to fight, fight on, evading death, but knowing each day of evasion they have exhausted one more chance of survival. Sooner or later, unless victory comes, this chase must end on the litter or in the grave.

OMAR BRADLEY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Without the time and effort of many dedicated people, this book would not have been written. The staff at the Special Collections Library at the University of Tennessee, especially Bill Eigelesbach and Nick Wyman, were always patient and accommodating. Thanks to them I was able to glean a remarkable archive of World War II primary sources, which have been compiled over the last two decades by the universitys Center for the Study of War and Society. The same was true for Richard Sommers, Pam Cheney, and Dave Keough at the U.S. Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. They and the rest of the staff in the archives branch never failed to point me in the right direction in my research. In addition, they worked tirelessly to assure that I received all the assistance and resources I needed. The staff at the Western Historical Manuscript Collection in Columbia, Missouri, also provided valuable help in navigating their extensive archive of World War II letters.

The History Department at the University of Tennessee and the Center for the Study of War and Society provided much needed financial assistance for my research. The centers World War II Veterans Project constituted the bedrock upon which this book was built. Credit goes to Dr. Russell Buhite, who gave unselfishly of his time and provided me with valuable insights. He has strengthened this work immeasurably. Thanks go to my mentor and dear friend Dr. Charles Johnson. He generously lent me his considerable guidance and expertise. His efforts in creating the World War II Veterans Project provided the necessary sources that made it possible to write this book. His knowledge and ideas about Americans in World War II have earned him a well deserved reputation of excellence in his field of study. He has provided wisdom, mentorship, insight, and, most importantly, friendship. He is the best teacher I have ever had. Without him, the following pages would not exist.

I would be remiss if I did not convey a word of thanks to the combat soldiers themselves. Rarely does the historian get to interact so intimately with his or her historical subjects. Throughout my work, the veterans whom I have interviewed or with whom I have corresponded have never failed to be accommodating and helpful no matter how foolish my questions might have seemed to them. Their courage and sacrifice were the original inspiration for this book.

The last word of thanks goes to my family. My wife, Nancy, has never failed to lend me her time and interest. It would be difficult to convey to her how much inspiration I draw from her love and from her belief in me. The greatest debt of gratitude belongs to my parents, Mike and Mary Jane McManus. Without their love and support this book would never have come to fruition. To them I am eternally grateful.

INTRODUCTION

Somewhere in the Ardennes Forest in a snowy, muddy hole with a small pool of slushy water at the bottom, an American soldier paused and collected his thoughts for a moment. Then he hoisted his weapon, left the dubious comfort and safety of his hole, and advanced toward his enemy while enduring machine-gun, small-arms, mortar, and artillery fire. He moved forward as he had dozens of times before and would dozens of times again if he wasnt killed or wounded. The reality for him was this: he had little or no hope of rotation out of his surroundings or transfer to a unit in safer circumstances. Combat was his world and he could hope to escape it only through death, wounding, capture, mental breakdown, desertion, orif he even dared imaginethe end of the war. To make matters worse, the law of averages stated with certainty that sooner or later he would become a casualty. It was not a matter of if, but when. Yet, in spite of his nightmarish existence, he continued, with dogged frequency and regularity, to fight and fight well, grimly moving forward to attack his enemy.

This drama was repeated millions of times, not just in the Ardennes Forest in the winter of 194445 but in other parts the world. In fact, at the same moment that the Ardennes GI moved forward, chances were very good that another GI was prowling through the mountainous, rocky terrain of Italy and yet another was doing the same thing in a steamy, forbidding jungle somewhere in the Pacific. What did they have in common? They carried out the same dirty, monotonous, dangerous job day after day and did it successfully. Yet not only did they do it in radically different circumstances against different enemies, but often they themselves came from completely different regional or ethnic backgrounds.

Ultimately the most basic question is why they did it. Why did these World War II American combat soldiers endure what should have been unendurable? What made them perform effectively and cohesively and draw on reserves of courage that they probably thought they did not possess? The answer is surprisingly simple. To a great extent they fought for one another; to an even greater extent they fought because of one another. The bond among American combat soldiers was so tight that it can be accurately termed a brotherhood. The GI leaving his foxhole in the Ardennes did it primarily because the next soldier was doing it too. He might not have even liked the soldier next to him, but he would do almost anything to help him. The same was true for his counterpart in Italy and in the Pacific. This bond was the single most important sustaining and motivating force for the American combat soldier in World War II. Although some individual units were more cohesive than others, the brotherhood was not unique to any one unit, sector, or theater. Rather it was pervasive among the troops who fought the war.

It is with those few who actually did the fightingthose at the so-called Sharp End, as historian John Ellis has termed itthat this book is exclusively concerned. Surprisingly little has been written on the American ground combat soldier in World War II. Of course there is no shortage of books on Americans in World War II, and often they include some discussion on the combat soldier. Good examples of this are Lee Kennetts

Next page