I wanted the book to be accessible for a general reader and so the transliteration of Arabic has been done with an emphasis on making it easy to read rather than strict accuracy. For the sake of consistency, I have used a capital and a hyphen for the widespread Al- prefix (meaning the) in all names, places and companies. All dollar figures are US dollars.

I spoke English with everyone I met in Qatar, but very few of them were native English speakers. As far as possible I have left their own words, including idiosyncrasies, intact not to poke fun or mock, but to convey what it is like to interact with others in English in Doha.

Not everyone I spoke to was happy having their name mentioned. When an asterisk follows the first use of a name, it indicates a pseudonym.

During the course of my research, I was a visiting fellow at Qatar University an unpaid position. Aside from a one-off honorarium for taking part in a media conference at Northwestern University in Qatar, I did not receive payment from any Qatari institution. x

I have gone in the opposite direction.

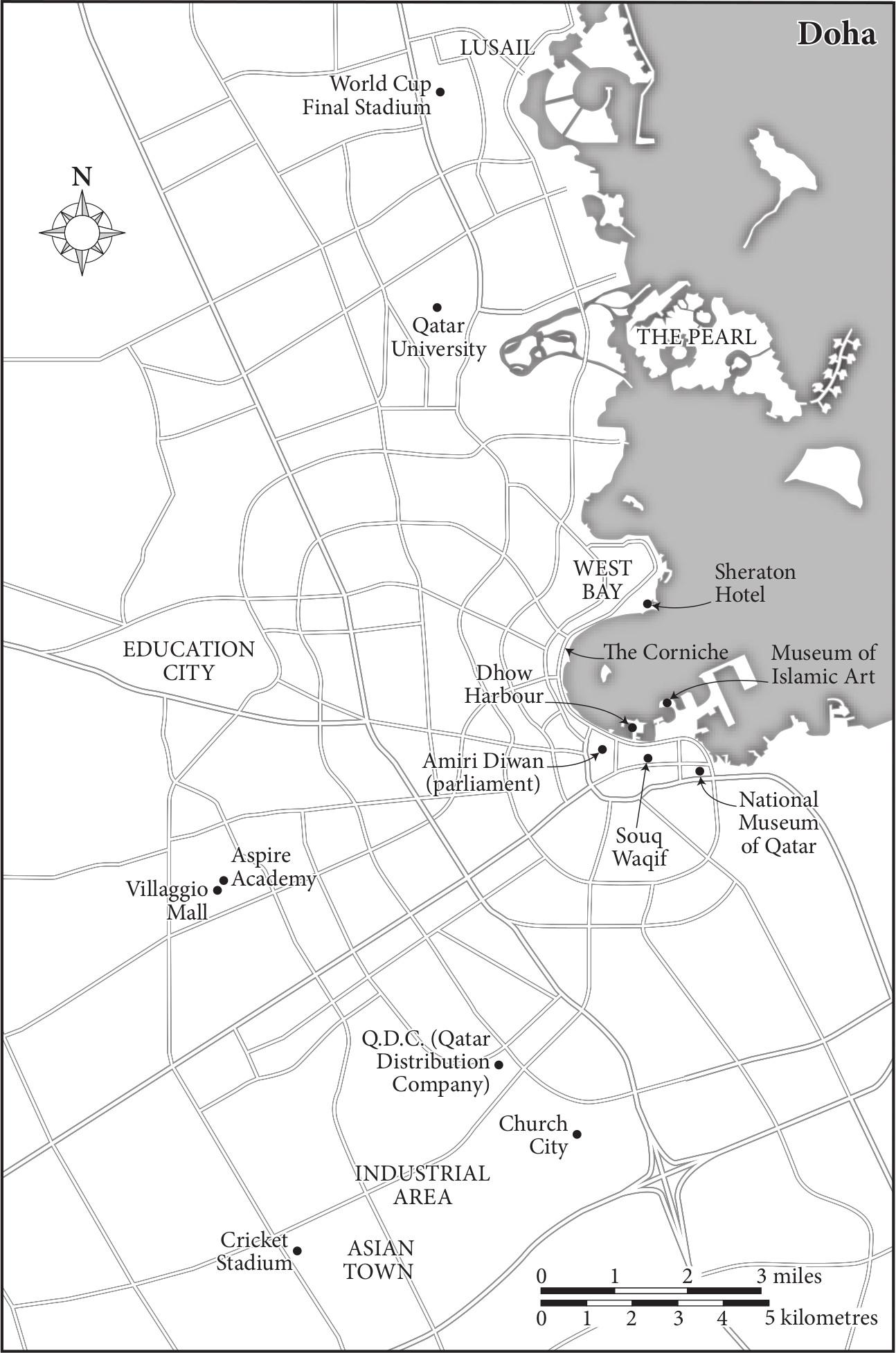

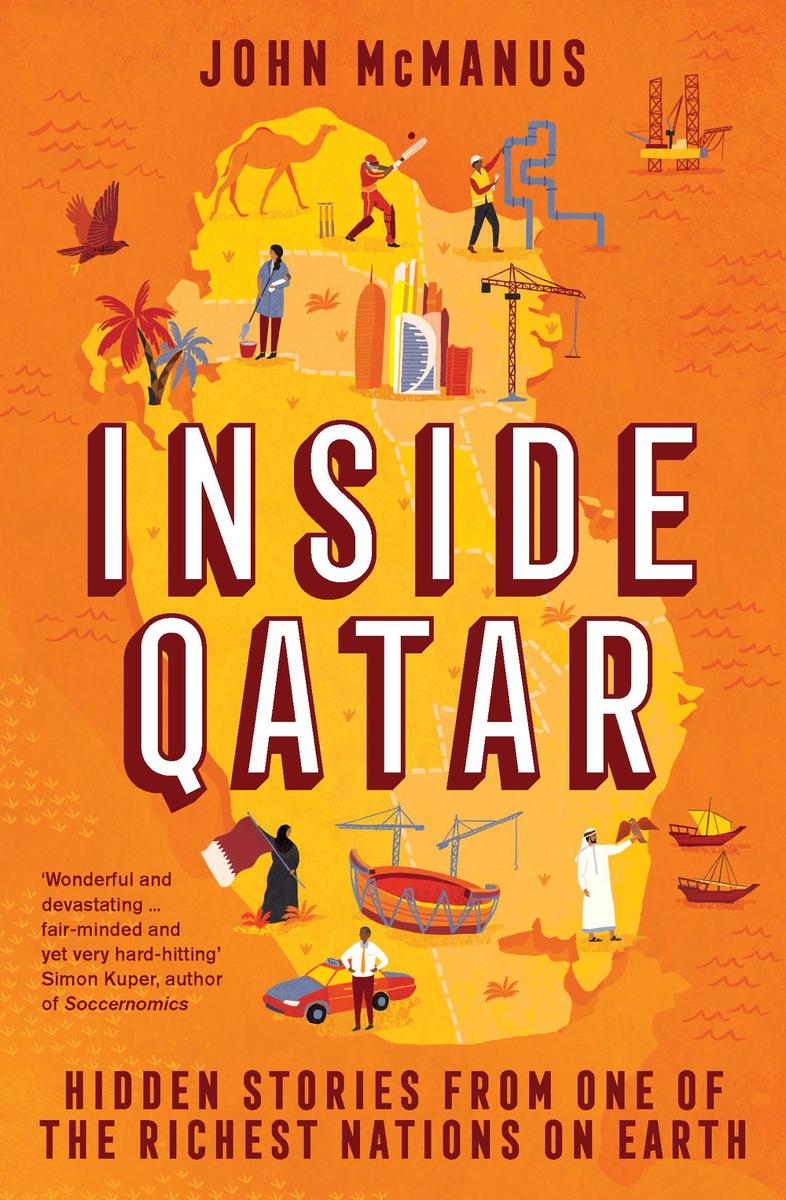

Away from the coast, the skyscrapers, the world-class museums, the traditional Souq renovated to within an inch of its life. Past the building sites of $600-million stadiums, heading south-west, in search of the answer to a question: what is Qatar like for most people who live here?

As I turn off the expressway, proportions seem to stretch and grow. Roads become longer and straighter. Kilometres of highway unfold without a kink, flanked on the right by a strip mall and then on the left, across scrubby desert, by the squat forms of labour camps.

It is Friday, the one day a week that most people (but not all) have off in Qatar. I now start to see some of them male workers coming and going. Some are in T-shirts and jeans, others shalwar kameez, a few in blazers.

I pull off the main road and into a large car park full of people and vehicles. I open the door and Im hit by the dusty, humid air. There are car horns and chatter and a restless, tense energy.

What is this place? Who are these people?

In a sense I can answer these questions easily: this is the Industrial Area, the district of Doha reserved for its most numerous residents the men working low-income jobs. More specifically, this is Asian Town, the newly built complex of malls, an amphitheatre and a cricket stadium that is designed to keep them amused and away from the rest of the population.

But in another way I cant answer these questions at all. Having arrived in Doha only days previously, I know nothing of years living apart from your partner and children; of being drawn by the lure of salaries many times what you could earn at home; of feeling disappointed, or worse exploited, broken by the ceaseless rotation of camp, bus and building site.

I leave the car and go into the small, covered arcade closest to me. I pass mobile phone vendors, jewellers, shops selling shoes, bags, consumer electronics even oil-filled radiators, a puzzling sight on a hot spring day but one I would later come to understand after experiencing a Qatari winter. The noise is cacophonous, with passers-by chatting to each other as they promenade and shop assistants shouting at them as they go past.

Hello my friend!

The use of English signifies this comment is aimed at me. I spin to see a young man, five-foot-five, beckoning to me from the entrance of his shop.

You want watch? Hublot. 240 rials [$65]. With nothing better to do, I follow him inside. The shop seems to have a lot of everything. Overflowing shelves rise up to the low ceiling. There is a waist-high glass cabinet, and the man is gesturing manically at items laid out on its top. You want scent? Or mobile? Orthis is Kuwaiti scent. Very special.

I shake my head. I dont use cologne.

No, me neither, says the man in agreement. You want sex ring?

Sorry, what?

Sex ring. You can go for two hours.

My mind cycles through the few things I know about Qatar. The population is overwhelmingly comprised of men, most of whom work six- or seven-day weeks and live in labour camps. Their contact with the opposite sex comes mainly in the form of the occasional interaction with a shop assistant or administrator. Workers have more opportunity for intimacy with each other, of course. But living four to eight people in a dormitory room does not exactly offer a lot of privacy.

I dont want to go for two hours! Ten minutes is enough, I say, attempting to defuse the awkwardness with a joke.

The guy looks at me and shrugs.

OK, so you go for 30 minutes then you pull it off.

I leave the shop and continue walking. There is a row of currency shops, their posters imploring me to send cash to loved ones in Africa and India. There are cafs selling Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Indian, Nepali and Filipino fare. One shop has a scrum unfolding inside. I watch as people tussle and shout to purchase various bulky, fluorescent suitcases. And everywhere there are men. They sit in clusters on the faded grass and stand in the arcades. They wander in twos and threes, arms round each others shoulders. They survey posters advertising music concerts and line up in huge queues at cash machines.

These are the men who have built Qatar. It is their tales that fill reports by human rights organisations and draw outrage in the West. It is on their backs that this peninsula the size of Devon and Cornwall, a place that even 30 years ago was a backwater, has become a country of villas, skyscrapers and football stadiums.

xii

xii