Preface to the Paperback Edition

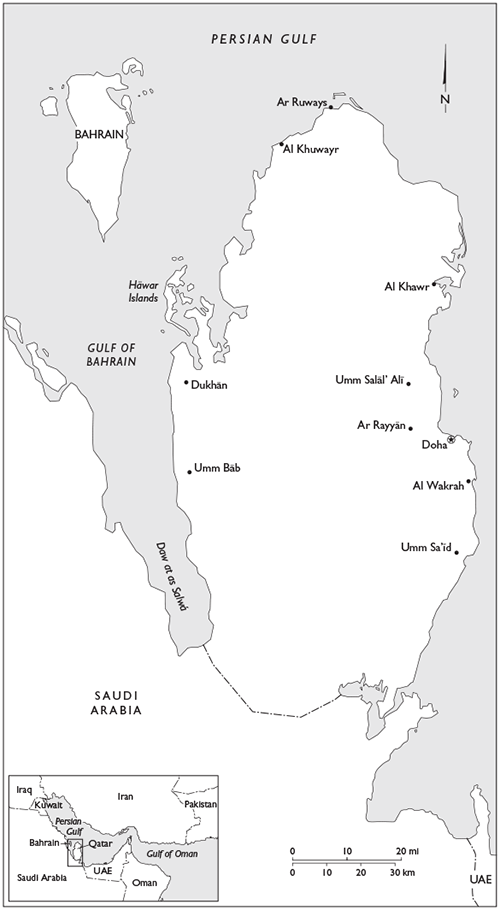

Much has changed in Qatar since this book was first released in the summer of 2013. As the book was making its way through the printing press, in June 2013, the countrys ruler, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, surprised long-time observers of Qatar, myself included, by announcing his retirement from the position of emir and passing on power to his son and heir apparent, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad. He was only sixty-one years old when the announcement was made, and Sheikh Hamads voluntary departure from office was nothing less than revolutionary in a region where leaders of all kinds, including supposedly elected presidents, seldom relinquish power voluntarily and are often forced out of office through coups or mass uprisings. Across the Middle East, in what one scholar has called a veritable kingdom of the old, Presidents-for-Life have historically competed with octogenarian kings and sultans in hanging on to power in their presidential palaces and royals compounds. The timing of Hamads retirement was particularly surprising given the continued unfolding of the consequences of the Arab Spring, and the ensuing multiple entanglements in the center of which Qatar had placed itself. In this preface, I will offer a few thoughts on the causes of some of the most consequential changes under way in Qatar since the books original publication, the shapes and processes that these changes have taken, and their consequences.

Perhaps the biggest changes in Qatar since the books initial publication have been in the areas of international relations and domestic politics. Political scientists and international relations experts have long called attention to the intimate nexus between domestic politics and foreign affairs and, as this book makes clear, at least in the contemporary Middle East, perhaps nowhere is this connection more pronounced than in Qatar. Mindful of this mutually reinforcing relationship, in this brief update I focus on four interrelated, potential areas of change that I believe have been most consequential both for Qatar itself and for the larger Persian Gulf and Middle East regions. These areas include Qatars domestic politics, its international relations, its economy, and the largely unintended consequences of its branding efforts in light of its successful bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

Domestic Politics

While the timing of the changeover came as a surprise, Sheikh Tamims ascension to power had been expected for some time, especially as he had assumed an increasingly higher public profile as early as 20092010. Significantly, 2013 marked the first time in Qatars history when there was a peaceful transition of power from one ruler to the next, a testament, as discussed in chapter 5, to the effective centralization and consolidation of power by Sheikh Hamad within his own household among the Al Thanis. Tamims on-the-job training had culminated in commanding Qatari efforts in Libya in the lead-up to Moammar Qaddafis overthrow, a task at which at the time he was generally thought to have been successful. With Qaddafis removal under his belt, Tamim in the position of emir initially steered Qatari efforts in Syria to replicate Qatars apparent Libyan success in shaping the direction of the Arab Spring. But, as we shall see shortly, this was not to be, and Syria turned out to be far more complicated than anyone, especially the Qataris, seem to have calculated. Even the Libyan success proved ephemeral, and before long Libya too was plunged into a civil war of its own, albeit one less intense than the ones raging in Syria and Iraq.

Qatars Libya and Syria policies raise the question of the degree to which the countrys change of leaders has translated into changes in policy and direction both domestically and internationally. With less than two years in office as of this writing, larger, more sweeping changes in direction under Tamim have been difficult to discern. Insofar as domestic politics are concerned, the same patterns of decision-making and policy implementation that had emerged under Hamad appear to have so far remained in place. As chapter 5 outlines, political decision making in Qatar is a highly centralized process that involves no more than a handful of individuals. With the transfer of power from father to son, the personalities involved have changed. But the largely informal structures of rule remain mostly intact. The former emirs wife, Sheikha Moza, for example, though not technically retired from public life, has adopted a much lower public profile since 2013, and is less visibly active in the countrys cultural arena, which was once perceived as her main area of concern. One of her daughters, Sheikha Mayassa, does however remain quite active and visible in cultural matters, heading the expansive Qatar Museums Authority. Also retired is Hamad bin Jassim Al Thani, the former emirs longtime prime minister and foreign minister and once perceived to be the countrys second most powerful individual. Tamim has appointed two separate individuals to each of these posts, neither of whom shares Hamad bin Jassims flare for the dramatic. In fact, with a decidedly different personality from his fathers, Tamim is himself not expected to replicate the media spectaculars his father seemed to relish.

These personality changes at the very top have not been accompanied by changes in the informal structures of high-level decision making. Nevertheless, Tamim has initiated institutional changes at other levels of the state bureaucracy. The new emir has brought with him new ministersonly a handful of his fathers ministers had retained their posts a year after the transitionand he has also centralized many offices within the ministries. Most major state industries have been undergoing shakeups in personnel and finances, chief among them the Qatar Investment Authority, the Supreme Education Council, the Qatar Foundation, the Qatar Museums Authority, and the state petrochemical company Qatar Petroleum.

In order to carry out his ambitious reform programs with minimal disruptions to institutions resistant to change, Sheikh Hamad had set up several agencies parallel to the regular state bureaucracy and had tasked them with implementing his ambitious developmental agendas. While quite an effective means of fostering change without precipitous social and political unease, this was an inherently inefficient and economically costly strategy. Tamim and his inner circle are fiscal conservatives who want to streamline the state bureaucracy without abandoning the developmental vision that had guided their immediate predecessors. One of the means of doing so has been to dismantle some of the parallel institutions, as was the case with the Qatar National Food Security Program, which was folded into the Ministries of Economy and Agriculture. Most other institutions have experienced budget cuts and even layoffs, as has been the case with the Doha Film Institute, the Qatar Museums Authority, and the Qatar Foundation. In his 2014 annual speech to the Shura Council, the emirs words of economic caution indicated the adoption of a more careful, deliberate policy on state spending:

I stress that the waste, extravagance, mishandling of State funds, lack of respect for the budget, reliance on the availability of money to cover up mistakes are all behaviors that must be disposed of, whether oil prices are high or low. Reasonable spending is an economic matter first and foremost, however, it is not only an economic matter but it is also a civilized issue related to the type of society that we want and the type of individual that we rear in the State of Qatar.