INTRODUCTION

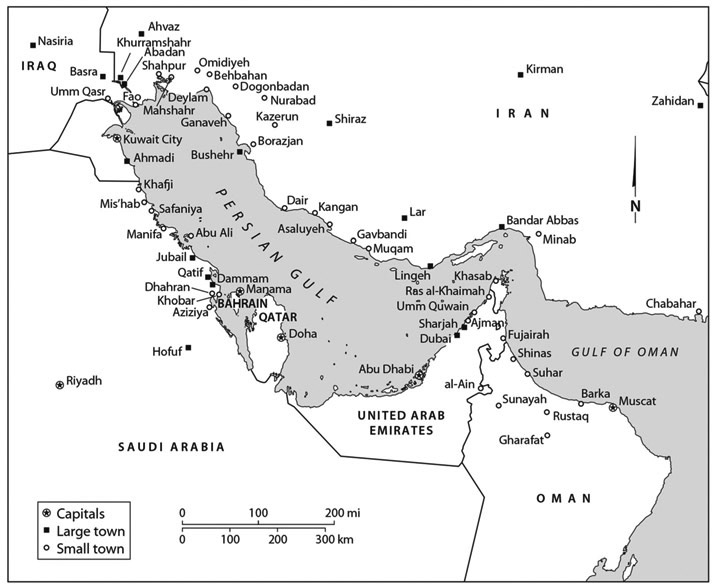

Why is the Persian Gulf so chronically insecure? This is the central question guiding this book. Today, the Persian Gulf remains one of the most heavily militarized and insecure regions in the world. This book examines, individually and collectively, the causes and consequences of these dynamics, which have made this small waterway and its surrounding areas one of the most volatile and tension-filled regions in the world. This pervasive insecurity, the book argues, is largely a product of four interrelated developments, the examination of which forms the central basis around which the books arguments are organized. Briefly, the four developments are preoccupation with conventional security threats at the expense of pervasive, though largely intangible, nonconventional critical security issues; the flawed nature of the prevailing security architecture, which, ironically, perpetuates regional insecurity; the deliberate actions and policies of the regional and extraregional actors involved in the Persian Gulf; and the self-reinforcing nature of the regions security dilemma.

First, I argue here that security threats in the Persian Gulf emanate from two complementary sets of sources. One set may be broadly labeled as conventional security threats, arising out of actual physical and military challenges to states. Some of the primary ingredients of these sorts of threats involve armaments and weaponry, high politics, interstate tensions, international intrigue, proxy wars, and cross-border conflicts. Just as pervasive, though perhaps harder to grasp and to quantify, is another set of security threats, namely, those arising from the consequences of perceived threats to culture and identity. It is precisely these challenges to what are broadly defined as human security that in the post-2011 context have fanned the flames of sectarianism across the region. For the most part, discussions of human security, or what has also been more broadly called a critical security perspective, have largely been academic in nature. But in the post-2011 period, the Persian Gulf offers a paradigmatic example of the concrete consequences of perceived threats to human security. The nature of security threats, and perceptions of such threats, are fluid and tend to change over time. In the post-2011 Persian Gulf, I maintain, focusing on one category of threats and ignoring other threats, which may be out of sync with our conventional notions of security, only gives us an incomplete picture.

The research for this book took me to several regional capitals, where I would typically meet with fellow academics and whoever in the various government ministries was willing to talk to me. In addition to learning that the waiting halls of foreign ministries must all have the same decorator, or at least have their furniture delivered from the same store, I was particularly struck by two exchanges I had with two of the regions most prominent policymakers. In my interviews I always included the same question in my list of inquiries: What is the biggest security threat your country faces today? Most often, I would get the answer I expected. In Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, for example, the answer was always Iran. In Tehran, it was The Gulf Cooperation Council and its American backers. But on two occasions the responses surprised me, not so much for the answer itself but for the honesty and foresight of my respondents. In Muscat, asked to identify the biggest security threat to Oman, without even a pause Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi bin Abdullah shot back, Unemployment. When I asked the question again, thinking it might have been misunderstood, he repeated his answer.

Something similar happened in another regional capital, where in a confidential interview with the minister of defense I asked for reasons behind the recent introduction of compulsory military service in the country. The response: to prevent boredom. Our young are easily bored, the defense minister explained, and they can fall prey to Daesh and its propaganda. Our goal is to keep them busy, give them discipline, and to instill in them a sense of hope in the future. The minister went on to confirm what those of us who live in the region feel viscerally, that there is a palpable sense of unease among many strata of society arising from perceived threats to cultural authenticity and to identity. If left unaddressed, such feelings have the potential of growing into serious threats to the state. That these worries were being expressed by no less than a defense minister, rather than by a sociologist or a social worker, was all the more interesting.

In the chapters to come, I place the importance of pervasive military threats in the Persian Gulf within the context of a broader array of security challenges that also include elements of human security. The prevailing security architecture of the Persian Gulf, I argue, has neglected some of the more pervasive security threats the region faces while exaggerating others for seemingly political and ideological reasons. Neglect of human security concerns, in particular, has given rise to issues of identity politics and sectarianism, which have in turn been manipulated by states for instrumentalist purposes.

A second, central argument of the book points to the role of agency in general, and individual policymaking and initiatives in particular, as one of the primary causes of the Persian Gulfs pervasive insecurity. Studying security in the Gulf reminds us of that simple truism in political science, that agency matters. Institutions may limit the range of choices available to policymakers, but not during critical junctures, as in the Arab Spring, or when leaders retain their supremacy over institutions, as is often the case in the Middle East. Much of the pervasive insecurity in the Persian Gulf, I argue, is not only the product of larger structural dynamics built into the regions security architecture. It is also a result of deliberate policies followed by regional actors, in collusion with their foreign backers, meant deliberately to identify and to undermine opponents. Many regional actors, I maintain, are willful belligerents.