For my mother, Elaine, who taught me to think critically and that history turns like a kaleidoscope; and for my father, Joseph, who taught me to embrace every day with hope and purpose and to love the meanings, sounds, and rhythms of words.

Contents

Janet Yellen followed her routine on the way to Washington, DC. She packed her bags carefully and arrived at the San Francisco airport early. She didnt like mishaps and she wasnt one to hurry while traveling, so she always left hours in advance to be the first person at the gate. There she sat, waiting for her long-haul flight to the East Coast while thumbing through briefing books prepared by her staff and playing Brick Breaker on her phone.

Yellen was a worrier, and she moved methodically. Her approach to life was to plan and prepare for all contingencies. For a woman making her way in a mans business, preparation was especially important. She worked details over in her head, reading up, thinking through scenarios, calculating probabilities for different outcomes, and sizing up strategies for how to respond should worst-case scenarios become actual problems.

She had picked up an exacting attention to detail from her mother, Ruth. When Yellen was a girl growing up in Brooklyn in the 1950s, Ruth often sent Yellens older brother, John, down the street to fetch the days newspaper. Then the children watched their mother sit with the paper, in a dress with her feet up on a couch, meticulously writing down daily stock prices she tracked on the back of envelopes in neat square handwriting.

Do your homework, Yellen learned. Dont be caught off guard by outcomes you could have foreseen. Eliminate worries. Reduce unnecessary risk. Prepare.

In December 2009 the United States was emerging from more than two years of shocking financial crisis. The economy was growing again. Janet Yellen, however, still had a great many worries.

Yellen was a central banker, sixty-three years old, one of twelve presidents of Federal Reserve banks spread around the country, two of which were run by women. Their job was to monitor the economy and the banking system, look out for problems like inflation or banks struggling with bad loans, and then work with the powerful Federal Reserve Board in Washington to figure out how to respond. When banks were failing, the Fed was called in to help sort their problems out. When the economy careened toward recession, the Fed had to rescue it.

The San Francisco Fed, which Yellen ran, was mandated to monitor a vast piece of the US economy covering 1.4 million square miles, from frigid mountain peaks in northern Oregon to dusty Native American tribal lands in the Arizona desert. In between were the nations hotbed tech market in Silicon Valley and pockets of some of its most unstable real estate markets, including Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and Phoenix. In all it had a greater land mass than India and was home to sixty-nine million people and thirty-one million workers, about a fifth of the nations population and a large part of the national economy.

During the preceding two years, a succession of big financial institutions had teetered or collapsed. Their top executives, typically the most confident of men, spent long weekends begging competitors and the Fed to save them during fraught rescue negotiations as frightened investors and depositors in their institutions fled for safety from the storm.

The list of casualties was long, diverse, and astonishing: Countrywide Financial, Bear Stearns, Fannie Mae, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, American International Group (AIG), Citigroup, General Electric, and many others.

Their problem was a mortgage meltdown. Americans had binged on mortgage debt in an era of low interest rates and financial innovation. They took out loans with unusual terms and used the cash to bid up the prices of homes, to pay for vacations and cars, or simply to cover their regular bills. Wall Street encouraged the frenzy, buying many of these mortgages and selling them to investors around the world in complicated financial packages. For a while this boosted profits and executive pay. Then overburdened households delayed or defaulted on debts. When mortgage delinquencies piled up, the financial system was starved of funds and nearly collapsed.

Some of the most aggressive mortgage writing happened in the West, which Yellen was monitoring. That meant she saw problems brewing early, though not early enough nor with the authority in a diffuse regulatory system to stop it.

As mortgages went bad, lenders panicked for funds, which in turn set off a frenzy inside the Fed to stop a potentially catastrophic crisis. The Feds healing medicine was money. It provided loans to banks when funds were nowhere else to be found. It tried to work in an orderly manner. In this case it administered its medicine as slews of patients crashed at its doors, convulsing and near death.

Yellen foresaw the panic before many of her colleagues at the Fed and urged them to move swiftly to stamp it out. The Feds responses prevented a financial collapse, but the nation was still left with something terrible. After two years of exhausting bank rescues, a recession had cascaded out of the canyons of Wall Street to communities across America, leaving more than fifteen million people unemployed.

In December 2009, Yellen didnt think jobs would be coming back anytime soon. As she saw it, this was the next crisis.

It all seemed so unfair. Wall Street got bailouts, and for good reason; the crisis revealed that the economy couldnt work if banks stopped making loans. But while the banks got support, millions of Americans were left behind to pick up the pieces of their lives with part-time jobs, food stamps, and disability claims. Two Princeton professors would later use the term deaths of despair to describe lives lost to depression, drug addiction, alcoholism, and suicide, a long-running trend that further signaled a nation where elites and everyone else were on two different tracks.

After landing in Washington, DC, that December evening, Yellen gathered with the eleven other regional bank presidents for an informal dinner in a hotel a few blocks from the Feds austere Depression-era building on Constitution Avenue. The next day the regional bank presidents met formally with five Washington-based Fed board governors and an army of PhD-trained staff to discuss the grim economic outlook and what to do about it. Technically economic output was growing again, which meant a recovery had started. Yet the unemployment rate had recently risen to 10 percent.

They sat in a cavernous boardroom with two-story-high ceilings, its tall windows decorated with elegant light drapes. Above the large mahogany table at its center hung a dark, pointed chandelier that hovered above their heads like the tip of a missile that had crashed through the building, poised to detonate.

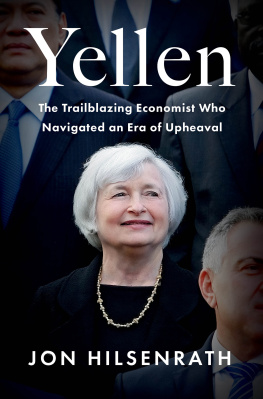

Yellen, who stood around five feet tall, wore modest dark pantsuits to meetings, sometimes dressed up with a silk scarf. Ben Bernanke, an introverted and socially awkward genius who had written books on the Great Depression, conducted the proceedings as the Feds chairman. As a young academic, Bernanke had concluded that the Feds hesitation to act had made the Great Depression much worse than it needed to be. He was a quiet man with bold views and the burden of orchestrating the Feds response. Bernanke had been in the job less than four years, having taken over from Alan Greenspan, a legendary central banker who led the institution through nearly two decades of rising prosperity and then retired just before the cracks in the economy were becoming apparent.

Fed staff sat along walls in a periphery of stiff chairs around the boardroom table, deciphering results from computer models they used to track the economy and predict where it would go next. One model had its own odd-sounding name: Ferbus, for FRB/US. This model had been created in the 1990s with great ambition and internal fanfare to simulate how the economy would behave under different scenarios. Punch in an oil price jump, and Ferbus would estimate how much less consumers, hit by higher gasoline costs, would spend, say, on cars or restaurant meals. Punch in a stock price boom, and Ferbus would say how many jobs would be created.

Next page