For Ffion and Seren

CONTENTS

This book is based on a dissertation the author prepared for the award of a Master of Arts degree in naval history at Exeter University in 2002, and much of the textual primary and secondary information used then has been incorporated into this present volume, although in some instances enlarged by further research. The advice and assistance provided by Exeter University staff where that earlier volume is concerned is still fully appreciated, as is the help given by the Librarian and staff of the Naval Library at Portsmouth and the Curator and Curatorial staff of the National Maritime Museums documents section, together with staff at Bath, Bristol, and Trowbridge reference libraries.

Where all the textual information used in this book is concerned, detailed and specific reference to individual sources has been made in the appropriate section, and a comprehensive bibliography has also been included. In the case of photographic illustrations, most have been used with the kind permission of the Curator of Photographs at the National Museum of the Royal Navy at Portsmouth. The small numbers of photographic images not so owned are from the authors collection.

A number of drawings have been included in the various appendices provided, and these in most instances have been sourced from nineteenth and early twentieth century publications that are long out of print. Very few drawings exactly like these appear to exist in later publications, and because of this it was felt that in celebration of what are in essence illustrations of contemporary engineering design and function, and in deference to their originators, who used them to illustrate certain concepts and aspects they were describing at the time, these drawings could be usefully included in this volume. By so doing it was hoped that readers would be assisted in appreciating more readily some of the descriptive narrative included in the book, and notes and source information for all these drawings are mentioned as appropriate in the section on sources.

Finally my special thanks go to my wife for her ongoing encouragement and practical assistance in a number of areas, including those associated with numerous textual issues and the organisation and presentation of many of the images I have used.

It should be noted also that where copyright might have been unintentionally infringed, the author will be happy to acknowledge associated sources and copyright ownership in future editions of the book.

1

In 1814, after more than twenty long years, the wars that Great Britain and other European nations had fought, firstly with Revolutionary and then with Napoleonic France, came to an end. Where Britain was concerned its navy had been a major participant in those wars as indeed it had been in the associated war with America that had taken place in 1812, and which had resulted in that country winning its independence. During the French wars the officers and men of Britains navy had built a reputation for their ability to exert command of the sea when this proved necessary, and to fully protect their island nation from any other naval forces that might be directed against it. This enviable position had for the most part been made possible by the stoutness and sea-keeping ability of the British ships, and by sound seamanship and a tradition of victory based on the navys disciplined fighting ability using the smooth-bore cast-iron guns that formed the armament of the wooden hulled ships in the nations sailing battle fleet. The apparently unassailable position that Britain thus found herself in was clearly of advantage militarily but, in addition, the resulting control of many of the worlds shipping routes meant that the ability to freely trade with her colonies, as well as other countries, rapidly increased both Britains wealth and her standing as a world trading power.

At the end of hostilities with France the British battle fleet consisted of some 218 line-of-battle ships and around 560 frigates and smaller vessels. In practice though, some of these ships had either been in continuous commission for a long time or had been hastily built during the war years, and were now in need of major repairs. Irrespective of this Britains six naval dockyards were unable to provide on-demand refitting and repair facilities to the extent that was required, and big backlogs of such work often occurred. There were numerous reasons for this, including poor accessibility to many of the dockyards from the sea, a lack of suitable dry docks and building slipways, a general shortage of storage and undercover working space, and highly labour intensive work processes that were very traditional and often unresponsive to new ideas and technologies. The effect of this was high costs, and repair work that had to be carried out over an extended period, with the result that only a proportion of the fleet could effectively be kept in service at any one time.

But with the ending of the Napoleonic wars the position rapidly changed, for although warships were still required to control trade routes, counter piracy, hunt down slavers, and protect British interests throughout the world, the need for a large and costly battle fleet in the post-war navy no longer existed. The British economy had been sorely affected by the extended war years, which had resulted in a national debt of around 900 million, and Parliament was soon calling for the adverse affects of this to be countered by savings in public spending. As a consequence the Admiralty agreed to maintain a much-reduced peacetime fleet of 100 ships of the line with 160 smaller vessels being retained for use as cruisers and on other support duties. Such a force it was believed would be adequate in use, and in any case would still be superior to the combined forces of the next two largest naval powers, which at this time were Imperial Russia and post-Napoleonic France, a country which on the ending of hostilities still retained many of the ships of its wartime battle fleet. The unwanted British ships were either scrapped or sold, with a proportion of those retained being mothballed and laid up in ordinary rather than being commissioned on active service. The existence of this reserve meant that for the first thirty years of peace very few new ships were built within the British naval establishment. The effect of these savings on the navys manpower strength was to drastically reduce it over a period of three years from 145,000 to 19,000, a saving of close on 87 per cent.

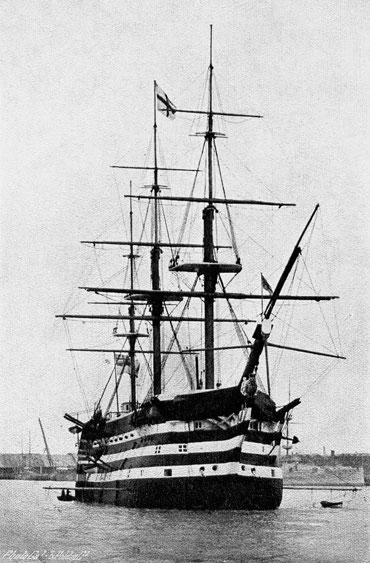

Three-decked 100-gun ship of the line Victory photographed in her old age, long after her active career had ended, but with her lower masts, topmasts, topgallant masts, and associated yards all in position. Probably taken circa 1920 when she was moored near Gosport in Hampshire. (Authors collection)

The line-of-battle ship of the early nineteenth century and the frigates, brigs, schooners, and other smaller warships that together formed the fleet, had changed little in form, construction, and function from those that configured the British navy of a hundred or more years before, and this was true of the naval forces of every nation in the world irrespective of their size, importance, or economic position. Built of wood with masts and sails for motive power and with their muzzle-loading smooth-bore guns all arranged on the broadside, these ships were of near uniform design across all navies in the western hemisphere. There was, however, some variation in classes, with the larger ships having three gun decks and three square-rigged masts that additionally carried some fore and aft sails, whilst intermediate and smaller sizes were provided with one or two decks of guns and relatively fewer masts depending on the size and type of ship. The very smallest vessels were normally rigged with fore and aft sails only, although some square sails were still carried for use, for example when running before the wind.