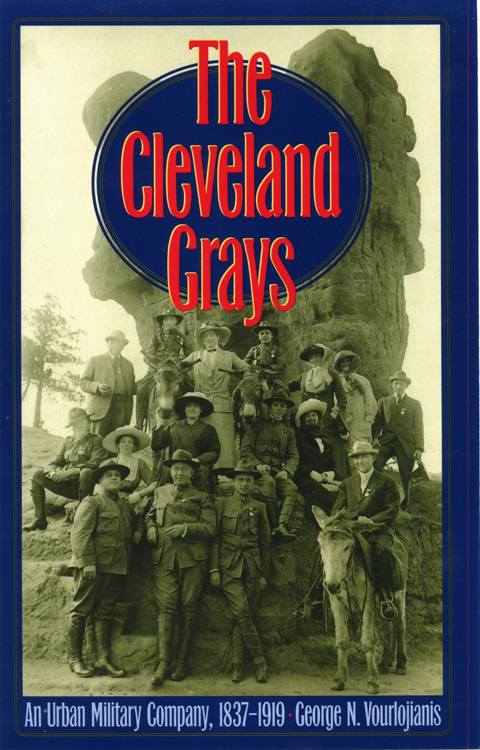

The

An Urban Military Company, 18371919

Cleveland

George N. Vourlojianis

Grays

THE KENT STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

KENT & LONDON

2002 by The Kent State University Press,

Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2001038315

ISBN 0-87338-678-7

Manufactured in the United States of America

06 05 04 03 02 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vourlojianis, George N., 1947

The Cleveland Grays: an urban military company, 18371919 /

George N. Vourlojianis.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-678-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Cleveland Grays (Militia unit)History.

2. OhioMilitiaHistory. I. Title.

UA398.C54 V68 2002

3553'7'0977132dc21

2001038315

British Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

To the memory of my father,

a U.S. infantryman of the Second World War

THIS WORK on a bit of Cleveland history began as a graduate Civil War seminar paper and developed into a dissertation under the direction of Dr. Frank Byrne, whose sagacious criticisms, never-failing encouragement, and limitless patience helped steer the work to completion. I owe a special debt of thanks to my old mentor at John Carroll University, Dr. George Prpic, and to Professors John Hubbell and S. Victor Papacosma of Kent State University for their wise advice and encouragement. Frank Tesch and Leslie Graham read through the manuscript on more than one occasion and offered sound organizational advice.

Next, I must thank Joanna Hildebrand Craig, Erin Holman, Perry Sundberg, Will Underwood, and the rest of the staff of the Kent State University Press for their professionalism and editorial acumen. I particularly thank Kirsten Lavell, who spent much time and effort working with the books many photographs. And Im grateful to the willing, helpful reference librarians and archivists at the City of Cleveland Archives; the Cuyahoga County Archives; the Ohio Historical Society Archives, Columbus, Ohio, the National Archives, Washington, D.C.; and the Western Reserve Historical Society of Cleveland, Ohio.

Finally, and especially, I offer tremendous gratitude to the Cleveland Grays, who graciously opened their archives and historic holdings to me. Grays archivist William Stark was especially generous with his time and advice. And members George Woodling, William Smrekar, John Jenkins, William Billy Hirsh, and a host of others contributed significantly to the writing of this book, offering moral support and other much valued help.

Semper Paratus!

AMERICANS HAVE never liked the idea of maintaining a large standing army or the thought of being forced into military service. However, despite this antimilitary bent in our national psyche, an army had to be organized and manned.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution recognized the militia, and the Militia Act of 1792 gave it its legal teeth. The Constitution placed the responsibility of appointing officers and prescribing training for the militia squarely upon the shoulders of the states, which often were unhappy about these new mandatory responsibilities. The organized or common militia had to be effectively administered, trained, and equipped. The procurement of arms and equipment was not only a time-consuming enterprise but also an expensive one. Service in the militia was also, generally, unpopular. Consequently, local politicians had no qualms about underfunding the militia or turning a blind eye to the enforcement of the law. The constitutionally mandated militia existed only on paper. As a consequence, in order to protect themselves from foreign invaders and bolster undermanned local police, groups of concerned, patriotic citizens in towns and cities throughout the country joined together and formed independent volunteer military companies.

The independent militia received no state or public support. State legislatures extended them statutory recognition. They purchased arms and equipped themselves with money from their own pockets. Because of this, membership tended to be drawn from the monied classes of the socioeconomic strata, the same group which owned property that might be at risk. Extra monies were donated by established members of the community. Leading local mercantilists became honorary captains in the independent militia. New members were screened and voted upon, thus adding to the social exclusivity of the membership. The style of their uniforms was inspired by European fashion, as were the names they chose: Cincinnati Rover Guards; Bostons Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company; Boston Fusiliers; Savannahs Chatham Artillery Company; New York Fire Zouaves; and Cleveland Grays.

The independent militia drew from the same pool of men from which the volunteer constabulary and the fire departments drew their prime movers and members. Their manly exercises fulfilled an assumed obligation of community stewardship, of Protestant noblesse oblige.

Independent militia companies were not, however, the exclusive domain of wealthy Yankees and Southern Cavaliers. During the first half of the nineteenth century, as part of an effort to combat nativistic sentiment, German and Irish Catholic immigrants banded together and formed independent military companies of their own. The main purpose of these units was to prove to their antagonists that they, too, were patriotic and loyal Americans. For many, military service helped open the door to respectability.

During times of national emergency, such as the Civil War or Spanish-American War, the independent companies lowered their stringent membership requirements substantially, so that their ranks could be expanded to meet the manpower needs of the conflict. After the crisis had passed and men returned to more peaceful pursuits, membership again became more selective. Still, egalitarianism would not be denied: the rosters now contained the names of a few Irish and Germans who had proved their worth in the company, perhaps under fire, and were now accepted as members. Also, these few were moving up the economic ladder and had the money to contribute to company military and social activities.

The independent companies had a social side that made membership in them attractive. These gentlemens military social clubs sponsored lavish balls, extravagant trips and grand outings for themselves and their guests. On patriotic holidays they sponsored band concerts and paraded through the city streets.

The decades following the Civil War were a double-edged sword for the independent militia. The era of urban unrest and violence unleashed by the burgeoning labor movement increased the militias role as urban police reserves. The local police were neither numerous enough nor strong enough to restore order and protect property. Many units of the ordinary militiaor National Guard, as they were now calledwere sympathetic to the strikers and were not trusted by those in authority. Hence the government turned to the independent companies, who had not only a moral but a material stake in preserving order and protecting property. In many instances the businesses and property being threatened by the disorderly belonged to them.