Copyright Peter Dorey 2019

The right of Peter Dorey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN978 1 5261 3828 6hardback

First published 2019

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

In writing this book, I have made extensive use of archival sources, some of which have only been made available to scholars relatively recently, while others have largely been neglected or overlooked, not least because the topic examined by this book has received only limited academic attention. I am therefore extremely grateful to the following individuals and organisations who very kindly and efficiently made sundry archives from 19689 available to me: Colin Harris and his colleagues at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, where I examined the papers of James Callaghan, Barbara Castle and Harold Wilson; the staff at the National People's Museum in Manchester, who provided me with the minutes of meetings of the (backbench) Parliamentary Labour Party, as well as the records of Tribune Group meetings; Mike Parker, who provided me with digitalised back issues of Tribune, the weekly paper published by the Tribune Group; James King and his colleagues at the Modern Records Centre, Warwick University, for providing me with the minutes of meetings both of the TUC's General Council, and its Finance and General Purposes Committee; the staff at the National Archives, Kew, for retrieving or photocopying Cabinet papers, correspondence between Ministers, minutes of a crucial weekend seminar held at the (then) civil service training college in mid-November 1968, and policy advice and proposals written by senior civil servants, as well as papers detailing the drafting of the 1968 Donovan Report.

Pete Dorey

Bath

May 2018

It was fifty years ago, in 1969, that a Labour Government sought to introduce legislation to reform industrial relations, and place Britain's trade unions within a clear legal framework. The proposals, enshrined in a White Paper entitled In Place of Strife, aimed both to imbue the unions and workers with various statutory rights and to impose particular responsibilities on them. The purported objective overall was to foster more orderly and responsible industrial relations, primarily in order to reduce the incidence of unofficial strikes, but also, ostensibly, as part of Labour's professed objective of establishing a Socialist society. A core component of this latter objective was much greater planning and regulation of the economy, coupled with the goal of establishing a fairer, more egalitarian, society. These objectives and goals were deemed to be seriously impeded by an apparently anarchic industrial relations system, and the readiness with which many trade unions used their industrial muscle, via strike action, to pursue short-term economic goals for their members, without regard for the longer-term material interests of British society overall.

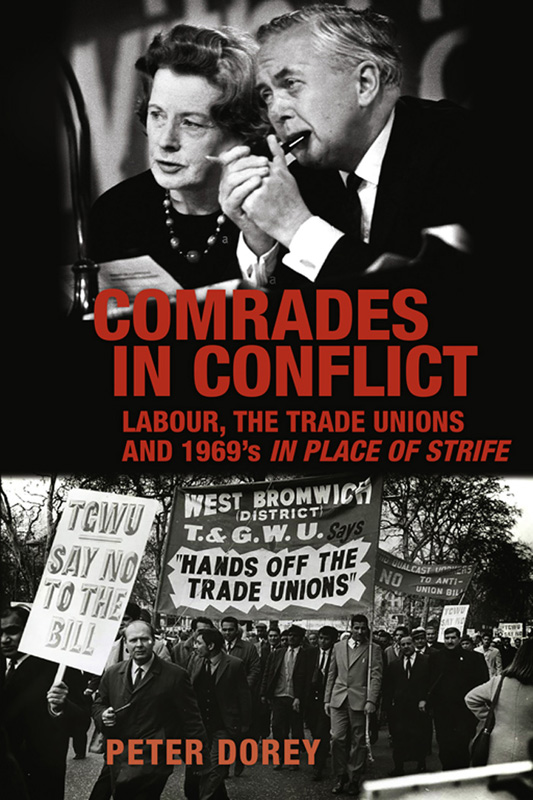

The two senior Ministers most closely involved in pursuing industrial relations reform via In Place of Strife, Prime Minister Harold Wilson and his Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity, Barbara Castle, were convinced that their legislative proposals were fair and equitable, in that they aimed to establish a balance between the rights of workers and trade unions on one hand, and the interests of the community on the other. They were adamant that their proposed legislation would not and was not intended to prevent or ban the trade unions from engaging in strikes in connection with disputes with employers, but that certain conditions should be met, and procedures adhered to, before strike action was embarked upon; it was about improving organisational processes, not imposing outright prohibition.

Yet while In Place of Strife appeared eminently reasonable to its political advocates, it aroused strong opposition from key sections of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP), a prominent Cabinet Minister, the Home Secretary James Callaghan, and from the trade unions themselves. Some of this antipathy had been anticipated by Castle and Wilson, but what surprised them, and ultimately proved fatal to In Place of Strife, was the scale of the opposition which it aroused, and the extent to which this increased during the first half of 1969. Castle and Wilson had envisaged that initial opposition would dissipate once opponents of In Place of Strife were persuaded of its alleged virtues, most notably the number of provisions it proposed to strengthen the trade unions and workers rights. In this regard, Castle had immense faith in her skills of persuasion, linked to a strong belief in the capacity of rational, reasoned argument to win over initial opponents.

Instead, the opposition aroused by In Place of Strife increased during the next few months, and was exacerbated both by the mid-April announcement of an interim Industrial Relations Bill (as a prelude to more comprehensive legislation planned for the next parliamentary session), and the appointment of a new Chief Whip, the supposedly disciplinarian Bob Mellish, who was widely expected to ensure the compliance of rebellious Labour MPs. Instead, his appointment inadvertently fuelled further anger among sundry Labour backbenchers.

Meanwhile, Castle and Wilson encountered implacable opposition from the trade unions, whose leadership, via the Trades Union Congress (TUC), bitterly resented statutory intervention in their internal affairs, and legal regulation of activities pursued in connection with collective bargaining. Some of the proposals enshrined in the White Paper and interim Bill offended against the unions long-standing commitment to voluntarism, whereby the State mostly maintained a non-interventionist stance towards industrial relations, thereby permitting unions and employers to negotiate terms and conditions of employment with a high degree of autonomy.