Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2020 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Richmond, Virginia, and the Valentine Museum, Richmond. Maps by Dick Gilbreath, independent cartographer.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-7925-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7928-5 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7927-8 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of University Presses |

Prologue

Death of a Nation

Died: Confederacy, Southern.at the late residence of his father, J. Davis, Richmond, Virginia, Southern Confederacy, aged 4 years. Death caused by strangulation. No funeral.

Richmond Whig, evening ed., April 7, 1865

The Confederate death certificate given as this chapters epigraph was published shortly after General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. Confederate president Jefferson Davis and members of his cabinet were on the run, attempting to make their way to the Trans-Mississippi theater.

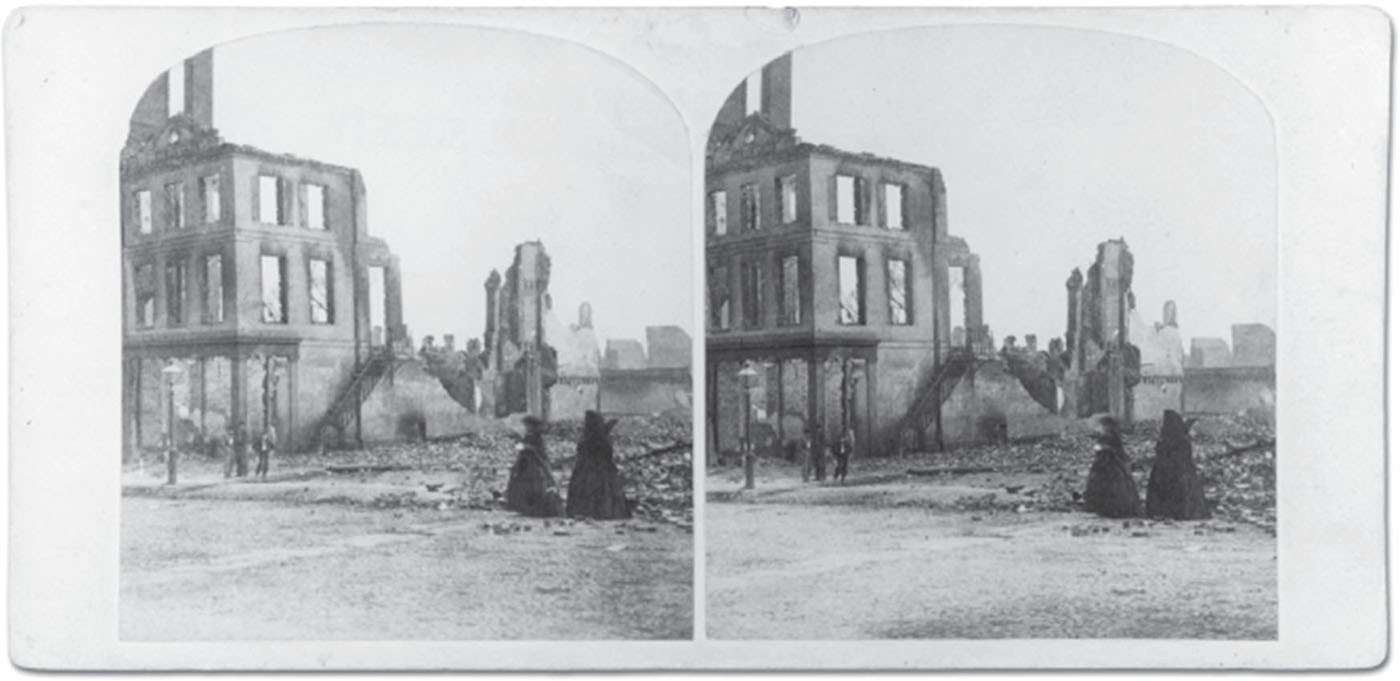

Davis and his cabinet left behind a capital city that was a shadow of its former self. As the Confederates evacuated Richmond, they put tobacco to the torch. A south wind whipped the flames out of control, and as the Federal army marched in, the business district was ablaze. Working to put out the fire, many of those in Union blue must have wondered if the loss of more than 300,000 Federal troops over the past four years was worth the cost of this victory; others probably questioned how such an upstart, largely overgrown town could have assumed such importance.

But it was in the rubble that locals and other curious onlookers could perceive Richmonds legacy. The burned-out business district bespoke of a diversified, developed commercial entrept. The hulking silhouette of the Tredegar Iron Works, saved by its workforce from an angry mob, testified to Richmonds singular importance as an industrial powerhouse within the Confederate nation. Indeed, the citys detritus spoke in mute testimony to the reality that it had transcended its symbolism as the Confederate capital.

From the time Virginia seceded from the Union and the Confederacy made the fateful decision to relocate the capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to the City on the James, politicians, the Northern public, and the Federal high command clamored, On to Richmond. The New York Times captured the prevalent spirit in the spring of 1861: Let us make quick work. The rebellion, as some people designate it, is an unborn tadpole. We have only to send a column of twenty-five thousand men across the Potomac to Richmond, and burn out the rats there.1 Sadly for those in both the North and the South expecting a quick and glorious victory, the rebellion would become a long, drawn-out, very bloody affair. It is not off the mark to argue that the war lasted four years because of the contributions the city and the people of Richmond made to the Confederate cause.

Women and ruins, 1865. Stereocard.

Previous studies of Richmond during the war have focused primarily on the city and have argued it was a place enamored of its past. A venerable city, it was laid out in the eighteenth century and over the years became intimately associated with the revolutionary legacy. One only had to wander to Capitol Square to see the imprimatur of the author of the Declaration of Independence: the imposing capitol building patterned after the Maison Carre in the south of France. Richmonders were proud of the role they played in Americas fight for independence and were quick to associate the First Families of Virginia with major milestones in the early republics history.

But declining economic fortunes and a rising tide of sectional politics jolted Richmonders and other Virginians out of their lethargy and spurred them to diversify the economy and to develop railroads. The result was a vibrant commercial, urban, and industrial complex by 1860. That renaissance laid the foundation for the citys remarkable wartime contributions. As locals mobilized and fought, they created a capital that transcended its symbolism as the center of the rebellion. Richmond and its people became the keystone of the Confederacy, the Southern nations impenetrable citadel. Once that keystone cracked under the pressure of war in April 1865, the Confederate citadel collapsed, and Robert E. Lee would surrender the Army of Northern Virginia one week later.

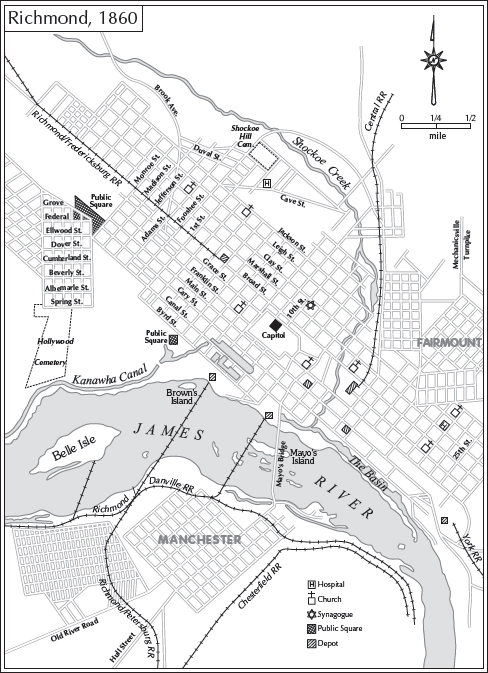

Richmond, Virginia, 1860.

In many ways, Richmond was an anomaly in the antebellum South. It stood as the future Confederacys second-largest city, and it had developed a very diversified economy by the 1850s. Indeed, in 1860 Richmond ranked thirteenth in the United States in manufacturing.2 The city enjoyed extensive trade relationships with the border South and with the Mid-Atlantic region. Richmond was heavily dominated by the Whig Party, although the national Whigs had died slowly during the increasing sectional conflict of the 1850s. The capital of Virginia also had a diverse population of Irish and German immigrants, Jews, free people of color, and slaves. As the war approached, Richmonds bondsmen played a critical role in the citys tobacco and iron industries.