Contents

Guide

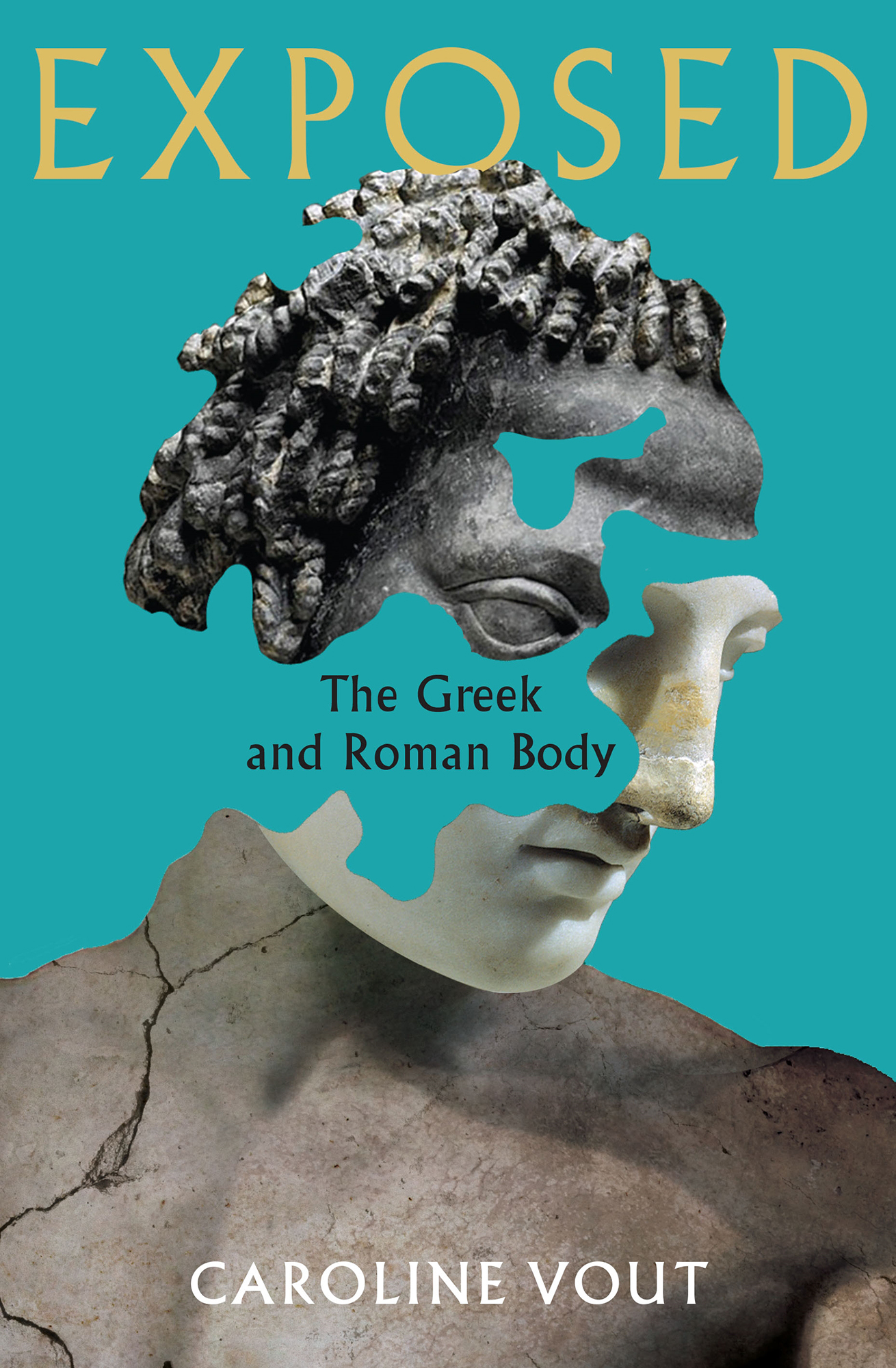

EXPOSED

EXPOSED

The Greek and Roman Body

CAROLINE VOUT

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Profile Books Ltd

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Published in association with the Wellcome Collection

183 Euston Road

London NW1 2BE

www.wellcomecollection.org

Copyright Caroline Vout, 2022

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 178816 2906

eISBN 978 178283 5738

For my father, Colin Vout

(25 September 1931 17 January 2020)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

W RITING a book takes its toll on the body not just the strained eyes, and the feet itchy to escape, but the soaring spirit when the words spill onto the page, and the fevered brow when there is a blockage. Lockdown intensified these feelings, as it did everything else our relationships with our bodies, and the bodies of our loved ones, these bodies relationship with society. Never has our temperature, our breathing, our sense of smell, our proximity to others been so freighted. I have tried to channel this.

This would have been impossible without my extraordinary colleagues, friends and family. I thank Gavin Francis, Kirty Topiwala and Andrew Franklin for giving me this opportunity, and everyone at Profile and the Wellcome Collection for helping me to see it to completion. Profiles Cecily Gayford has been the most exceptional editor and I cannot praise her enough: her instincts are always spot on, her feedback as brilliant as it is sensitive. Excellent too has been my copy editor, Susanne Hillen.

I also thank the University of Cambridge and Christs College for granting me the sabbatical leave to write this, and Leiden University and the Byvanck family for giving me formal links with a third august institution. Mary Beard, Alastair Blanshard, Rebecca Flemming, Simon Goldhill and David Sedley helped me hugely with feedback on the proposal or on individual chapters, and Ingo Gildenhard, Kathryn Stephens and James Warren by discussing some of the literary, historical and philosophical aspects.

I owe my lockdown sanity to Satyam Yoga, and its amazing teachers, to all of my friends, especially Ned Allen, Emily Gowers, Dai Jones, Rosanna Omitowoju, Maryam Parisaei, Helen Pfeifer, Amit Shah, Henry Spelman, Natasha Tanna and last but not least to the awesome graveyard crew, Nick Gay, Torsten Krude and Harriet Lyon. Harriet deserves special thanks for reading the typescript in its entirety. And I thank my husband, Robin Osborne, who read the typescript more than once, and jogged beside me every step of the way. I would be a lesser person without him.

Still, the last two years have taken their toll on all of us. I reach out in particular to my mum, Ann, and my sister, Sue, and remember those who are no longer with us at the end of this journey not only my darling dad, to whom this book is dedicated, but my colleagues Chris Abell, Neil Hopkinson, Ian Jenkins, Peter Lachmann and John Salmon, as well as two of the teachers who introduced me to things Greek and Roman at school, Barbara Stephenson and Dorothy Woodman.

CAROLINE VOUT

CAMBRIDGE, SEPTEMBER 2021

PROLOGUE: NAKED, NOT NUDE

I NEVER meant to write a book about the body or at least not the body as an entity. My plan had been to work on faces, and on what the lives of individual ancients might look like when reconstructed not from texts on paper and stone, but from Greek and Roman portraits. Either that, or I would try my hand at a history of Greek and Roman sexualities. But both of these projects fragment the body, denying it its role as social animal. Why stick at heads or genitals?

Two events collided to embolden me. I was invited to speak at the launch of Shapeshifters: A Doctors Notes on Medicine & Human Change, by the doctor and writer Gavin Francis, and asked to devote my brief appearance to the Latin poet, Ovid. We were at the Wellcome Collection in London, an institution best known for its study of health and science. I crossed my fingers, and explained how in Ovids most famous work, the Metamorphoses, the body was the source of all knowledge; how its stories of bodily transformation (into animals, trees, flowers, stones, rivers, stars, gods, girls into boys, boys into girls, man and woman into hermaphrodite) spoke to modern anxieties about nature, culture, sex, gender, body dysmorphia. My listeners nodded. Their questions about diet, disability, suicide, selfhood showed that the Greek and Roman body had barely aged. Ovid is as adept as he ever was at asking what it is to be human.

The second event made the local paper: Cambridges Bridge Street closed after cyclist hit by mobility scooter. I remember flying, too high, like Ovids Phaethon, who loses control of his fathers fiery chariot and then a fifty-five-minute wait for the ambulance. I was conscious, my only lasting injury a break to my writing arm. Now I had more questions in common with Ovid: about the relationship of man and machine, about mind and body, about bodily integrity. I was subsequently told that eleven of the skeletons found at the Roman cemeteries of Poundbury in Dorset and Lankhills in Winchester have healed fractures of the very same radius bone none of them, I am pleased to say, with poor alignment of their limb, or excessive limb shortening. Was their treatment similar to mine? Was it similar to that found in the treatises of Greek and Roman medical writers? Had I been around back then, chances are that a horse and cart would already have mown me down: I have been short-sighted since my teens, and, although the Romans did experiment in eye surgery, I would have had to wait a millennium and more for glasses. The body is all I think about. I ask my colleague: Can I really start a book in this state?

She replies: Its perfect timing.

Perfection. The Greek and Roman body is a flawless body, lean, lovely, on a pedestal. It is also a beautiful lie. Even the greatest painters of the period struggled to find inspiration in a single human, taking the best bits of several sitters to fashion a flawless composite. Meanwhile, sculptors made bronze and marble bodies that were too good to be true or truly mortal. Greek sculptor Polyclitus is a good example: from the outset his Spear-carrier was deemed paradigmatic of the human form (). Made in the fifth century BCE , the statue is now lost, but not before admiration of it had led to multiple Roman copies. Let us pause for a moment over its youthful face, mature torso, and incongruously tiny penis. It makes the point (a point that was frequently debated by the ancients) that the requirements of art are different from life.