CONTENTS

BARBARIANS

in the

Greek and Roman World

BARBARIANS

in the

Greek and Roman World

By

Erik Jensen

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2018 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Rick Todhunter

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jensen, Erik (Professor of history), author.

Title: Barbarians in the Greek and Roman World / by Erik Jensen.

Description: Indianapolis : Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017056973| ISBN 9781624667121 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781624667138 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: GreeceCivilizationInfluence. | GreeceCivilizationForeign influences. | GreeceCivilizationTo 146 B.C. | RomeCivilizationInfluence. | RomeCivilizationForeign influences. | AcculturationGreeceHistoryTo 1500. | Acculturation History.Rome

Classification: LCC DF78 .J45 2018 | DDC 303.48/438dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017056973

ePub3 ISBN: 978-1-62466-764-0

Race and Ethnicity in the Classical World: An Anthology of Primary Sources in Translation . Selected and Translated by Rebecca F. Kennedy, C. Sydnor Roy, and Max L. Goldman.

Ancient Rome: An Anthology of Sources . Edited and Translated, with an Introduction, by Christopher Francese and R. Scott Smith.

Herodotus, Histories . Translated by Pamela Mensch. Edited, with Introduction and Notes, by James Romm.

Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook . Edited and Translated, with an Introduction, by Brian K. Harvey.

Robert Garland, Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks , Second Edition.

David Matz, Daily Life of the Ancient Romans .

CONTENTS

The page numbers in curly braces {} correspond to the print edition of this title.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people have helped to shape this project and bring this book into being. I am grateful to Rick Todhunter, Liz Wilson, and the rest of the team at Hackett for their tireless work, endless kindness, and invaluable support. Al Andrea and Stanley Burstein pushed me to think more carefully and write more clearly, for which they have earned my profound gratitude. I thank my colleagues in the History Department at Salem State University for setting such a high standard for me to live up to (especially my confidante and coconspirator Margo Shea, who helped preserve my sanity through the most difficult parts of the process), and my students for always making me ask new questions. I am also deeply grateful to my former professors David Castriota and Natalie Kampen, for guiding me to think more deeply about cultural interactions in the ancient Mediterranean. This book is the culmination of the passion for ancient history and art history that they inspired in me many years ago.

The final and highest thanks go to my wife, Eppu Jensen, not only for her patience and support in this project but also for her detailed and critical reading of my first drafts, without which the best parts of this book would never have been crafted.

{vii}

The civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome did not flourish in isolation. They were part of commercial, cultural, and political systems that spanned Eurasia and Africa. Greeks and Romans lived, traded, exchanged ideas, and sometimes fought with peoples of many other cultures. To describe these peoples the Greeks invented the word barbaros , which the Romans adopted as barbarus . Sometimes these words carried a pejorative sting, but in other cases they were simply acknowledgments of cultural difference. Similarly, the interactions among Greeks, Romans, and other peoples were sometimes fraught with conflict but at other times peaceful and productive.

Histories of these interactions written before the late twentieth century tended to focus on wars and politics, with little attention to the complexities of identity in a multicultural, multi-ethnic, and multilingual world. Important work has been done in the field in recent generations, but much of contemporary scholarship has been focused on particular areas and topics whose connections to one another are not obvious at first glance. For those coming to the question without many years of study behind them, the subject can be an impenetrable one. This book looks at both the realities of the multicultural ancient world and the ways in which the Greeks and Romans attempted to understand it.

Why a History of Barbarians?

A history of barbarians in the Greek and Roman world serves two purposes. First, it places the history of Greece and Rome in a larger world-historical context. Second, it helps us understand the ways in which Greek and Roman ideas continue to shape how Western societies deal with a multicultural reality.

The ancient Mediterranean was a cosmopolitan place. Phoenicians, Greeks, Egyptians, Carthaginians, Romans, Etruscans, Gauls, and many others traded in the regions great market cities. Beyond the bustling Mediterranean, Greek voyagers ranged from the North Sea to the Indian Ocean. Roman soldiers marched from the deserts of Morocco to the edges of the Eurasian steppe. People, goods, and ideas flowed along routes that reached east to China, west to the Canary Islands, south to sub-Saharan Africa, and north to the Arctic. The societies we today think of simply as Greece and Rome existed within larger cultural contexts and included people of many different cultural and ethnic backgrounds.

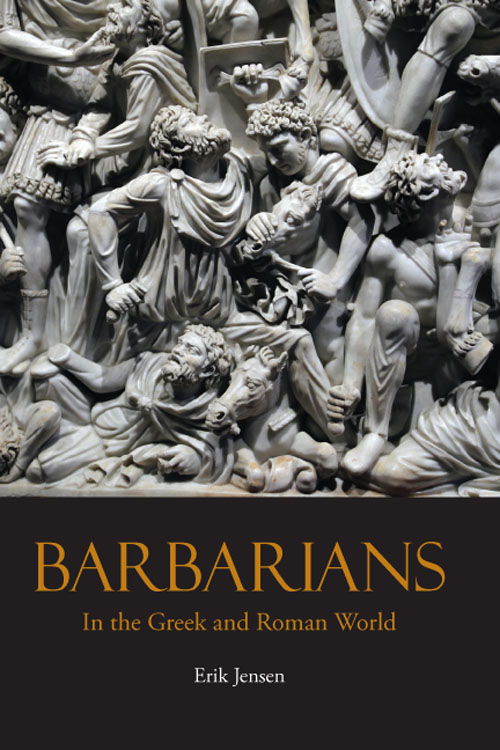

{viii} An artists vision of the burial of the ivory bangle lady, reflecting the ethnic diversity of late Roman York.

{viii} One example may stand for many others. A wealthy lady was buried in York in northern England in the fourth century CE with an assortment of bangles, some of white ivory from Africa, others of black jet, a gemstone mined in Britain. Examination of the remains using the techniques of forensic anthropology shows that she was of sub-Saharan African ancestry and had spent her childhood in a warmer climate, perhaps somewhere in coastal Western Europe. While the ivory bangle lady left us no record of her own thoughts about her identity, she was clearly a person of wealth and status, and her choice of jewelry suggests a consciousness of being both African an d Brit ish.

She was not alone. Individuals from Gaul, Italy, and Egypt are mentioned in Roman-period inscriptions around York. Local potters made cooking vessels characteristic of North African cuisine. The emperor Constantine began his rise to power in the city in 306 when he was first declared emperor by one of his companions, a Germanic king. Examination of burials in the city suggests that the population of York in the fourth century may have been more ethnically diverse than it is today. The northernmost city of any size in the Roman empire, York was far from the cosmopolitan urban centers of the {ix} Mediterranean. But even in York, people of many different backgrounds lived and worked together.

Greek and Roman writers were aware of the cultural diversity of the world they lived in, and they had varying reactions to it. Some were contemptuous of other peoples. Others were aware of cultural differences and, though they preferred their own ways, did not look down on the ways of others. Some admired foreign customs. Many invented links between themselves and other peoples or sought to blur the lines that separated one people from another. Some saw in foreign peoples the opposite of their own identities, while others saw people much like themselves. No single narrative dominated how the people of the ancient world thought about their cultural differences.