First published 2002 by

Routledge

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2002 by P. Rene Baernstein

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or In any lnformatlon storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

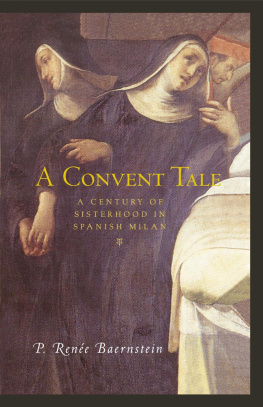

Baernstein, P. Renee.

A convent tale : the Angelics of Spanish Milan, 1535-1635 / P. Renee Baernstein.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. San Paolo Converso (Milan, Italy)History16th century. 2. Milan (Italy)Church history16th century. 3. San Paolo Converso (Milan, Italy)History17th century. 4. Milan (Italy)Church history17th century. I. Title.

BX2624.M476 .B34 2002

271'.97dc21

2002002614

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-92717-8 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-92718-5 (pbk)

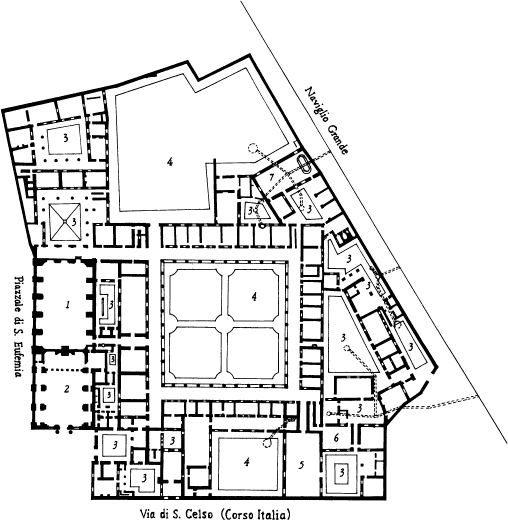

. Floor plan of the convent of San Paolo Converso in Milan

. Italy, 1559

. Milan, 1573

. Ludovica Torelli, Countess of Guastalla

. The Sfondrati family tree

. Antonio Campi, Beheading of St. Paul

. Antonio and Vincenzo Campi, Assumption of the Virgin

. Antonio and Vincenzo Campi, Ascension of Christ

. Antonio Campi, Martyrdom of St. Lawrence

. Ercole Sfondrati, Duke of Montemarciano

. Church of San Paolo Converso, eighteenth-century view

. Circle of Giovanni Battista Crespi, Il Cerano, Carlo Borromeo with Angelics

. Church of San Paolo Converso

Archival historians, like fishermen, are a morose lot, prone to tall tales and laments. When they gather, the talk inevitably turns to the tale of the Great Document bagged in the face of prodigious obstacles. Next comes the story of the Document that Got Away, something spotted once perhaps by a nineteenth-century antiquarian and never seen again despite the researchers dogged dragging of nets across every archive in the country.

This book has seen its share of documents that got away. In fact, it owes its very existence to archival misfortune and serendipity. Some years ago, as a graduate student, I went to Milan to research a dissertation on the culture and politics of that city at the beginning of the Spanish domination (1535). The ItalianSpanish encounter, I thought, would surely have spawned a rich and complex set of documents. I soon discovered I was mistaken: That encounter was less intense than I had hoped, and in any case the vagaries of war and other catastrophes meant that almost no political documentation remained of Milan in the 1530s.

While I was casting about for a replacement topic, chance threw an issue and a document my way. The issue was gender, a subject that in truth had interested me little to that point. Like many women of my generation, I disdained aggressive feminism and its seemingly shrill attention to womens past. I was grateful to my foremothers, whose feminist revolution had made my career possible, but I believed that battle was over. Hadnt we won? Surely now it was time to get on with the business of beating men at their own games. Womens history, I thought, was for sissies.

Italy forced me to reconsider my position. There, the casual street attention paid to young women, particularly foreigners, left me feeling harassed and reluctant to leave my apartment. That my Italian women friends found my predicament amusingand my subway suitors sometimes interestingonly confused me further. Isolated and puzzled, I withdrew from public life, going out only when I had a short simple errand or when a friend could come along. The reading room of Milans Biblioteca Ambrosiana became a favorite refuge; there I cast my lines into one fondo after another, angling somewhat randomly for a juicy catch from the sixteenth century.

The eureka moment came one day as I leafed through the manuscript diary of Gianbattista Casale, a sixteenth-century woodworker. Casale taught boys their catechism in the Schools of Christian Doctrine, a confraternity-like organization created in Milan in the 1530s and expanded dramatically by Archbishop Carlo Borromeo after 1565. As I read I recalled that other religious institutions of the 1530s, too, saw new life and new direction under Borromeos rather forbidding command. What could those institutions shifts tell us about the changing shape of religious experience over the century? With that question in mind I consulted one of the massive biographies, or rather hagiographies, of Borromeo published just after his death in 1584. There the author, Carlo Bascap, credits Archbishop Borromeo and his associates with reforming all manner of schools, clubs, monasteries, etc., andthe words now jumped off the pagewith confining all nuns of the diocese to their convent quarters, imposing enclosure on them in accordance with the 1563 decrees of the Council of Trent. The penny dropped: I was enclosing myself! And it had been done before, in the sixteenth century! The differences between past and present, of course, far outnumbered the similarities. To begin with, male authorities imposed sixteenth-century enclosure on nuns, or so Bascap and most subsequent historians have asserted; I, in contrast, had sheltered myself voluntarily, in a defensive maneuver. Nonetheless, the parallel resonated with me, and so this book was conceived: the story of the convent of San Paolo Converso, whose nuns first tried public life and then found themselves enclosed.

Giving my predicament a historical pedigree, however strained, somehow made it easier to make my peace with life in modern Italy, and by the end of a three-year stint there I felt that land to be a kind of foster home, pleasantly familiar yet foreign. But my early unease did have a profound and ultimately positive effect on my politics and my work. Coming face to face with another cultures problematic gender relations forced me to confront the complexity of those relations in my own culture, that of the United States. Now the feminist victory in the United States seemed less complete, more ambiguous than I had thought. I returned from Italy a committed feminist and a historian of women and gender, both transitions that have required considerable reeducation.

This expedition has yielded some satisfyingly big fish caught, and some that slipped awayand sometimes, I got tuna when I expected swordfish. For example, convents have often drawn the attention of scholars seeking a model of female solidarity, perhaps a model that could have lessons for modern womens organizations. Somewhat to my surprise, I have found very little gender solidarity in San Paolo. Its nuns divided among themselves along class lines or along factional lines; only rarely did they join together as women against an outside force. One of my conclusions, therefore, is that individual Angelics must be situated in their full political and social context. Despite their thick walls, nuns were very much integrated into their communities and were at least as concerned with those larger communities as they were with their own houses. Gender solidarity, alas, proved to be a chimera. Enclosure itself proved, in some respects, to be chimerical too. Even during the most severe of enclosed regimes, San Paolos nuns looked outward, interacting with the wider world. Their storied resistance to enclosure likewise dissolved under scrutiny: Most of the nuns of San Paolo eagerly embraced the change in their lifestyle. This book asks why most did so, why some did not, and how the nuns of the community shaped their individual and collective identities within and across the convent walls. It departs from the very unmodern notion that a woman might, under certain circumstances, choose to lock herself up.