Table of Contents

For David Cowan

Authors Note

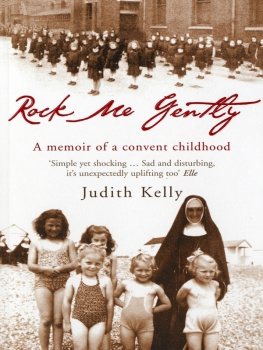

This is a work of nonfiction. But some small amount of fictionalizing seemed inevitable from the first: as a young nun (forty years ago), I kept no journal. I have invented a few details so as to make up for insufficiencies of memory; in this way I hoped to give more, not less, of a sense of things as they were.

The larger events and encounters all actually happened; the reader might want to know that in this area I made up nothing. My remembrance of 19601965 never felt like a conventional narrative, though it had progressions. My sense was more of a string of paper lanternsElaine Pagelss epinoia... hints and glimpses, images and storieslit spottily against the dark along a dock, where some days, even now, waves dash.

A few persons have told me that they did not wish to be identified here (even if their words and actions would have cast them in the most favorable of lights). I have omitted some names, then, and changed others; I also occasionally altered locations, small details, and sequences of events. I did the same for those people from my past life whom I could not contact. Random initials identify some nuns because of the plethora of proper names that were (or are) actually in use in the BVM Community.

PART ONE

Becoming a Postulant

Taxi

Blue smoke curled out of the taxicab windows.

The driver, who had just parked outside what looked like a stone mansion, waited; he had most likely been through this before. Three of us, three young women, sat in his Yellow Cab and smoked our cigarettes.

The mansion was the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. And this day, July 31, 1960, was Entrance Day, the day we would give our lives to God by joining the convent. About two weeks earlier, on the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, on July 14, I had celebrated my nineteenth birthday.

Other taxicabs were pulling into the motherhouse like limousines to the Oscar awards or like horses to the Bar X corral. One hundred and eighteen of us wanted to become nuns.

Many of us were edgy and sat smoking and speculating a little, like starlets or cowpunchers before it was time to crush out the cigarettes or flick them away and do the next things that needed to be done.

Edgy, yes, we werebut also blithe to become nuns, just as Thomas More had been blithe to bare his neck and have his head neatly sliced off by the likes of the black-hooded executioner in AMan for All Seasons. Thomas was so chipper because he knew he was headed for God, would see God face-to-face. Robert Bolt has Thomas sayor maybe Thomas said it himselfthat God will not refuse one who is so blithe to go to him.

In a way, we were going to Him now.

I was going to Him now. When I died, why would He refuse me if I had been a good nun? It was quite a bit like being a princess; eventually I would come into my own and inherit the transfigured earth and the kingdom of heaven.

Maybe the Yellow Cab driver, unless he was Catholic, actually did think he was my executioner. I would give him a big tip, all the money I had left, and I would give him the rest of my cigarettes.

The motherhouse, the convent of wine-colored stone, looked huge as a Cotswold manor house or an estate in Croton-on-Hudson. But the river at the base of the bluffs on which this building stood was the Mississippi, as it flowed past the southern edge of the city of Dubuque, Iowa.

In 1960 most of us didnt know much about the path of the Mississippi or the life on it or where the bluffs began or ended. Did the river mostly remind us of the flux of all things, or even of Jim and Huck? It did not. It might have been the Tiber or the Loire, the Tigris, the Ruhr, or the Yangtze. No matter. What we wanted that day was to become nuns.

We didnt give a fig about our position in the landscape.

Smoke

My friends Teresa (Tessa) and Kathleen (Kathy) and I thought of ourselves as savvy. We knew what to do because another friends sister, who was already a nun in the order we were joining, had told us the tradition. On Entrance Day we were to give our last cigarettes to the cabdriver.

We three had come in the Yellow Cab across a bridge over the river, from the train station in East Dubuque, Illinois. We had gotten on that train at Union Station in Saint Paul, Minnesotaour hometown.

Twelve young women in all had come from Minnesota to be nuns, but I knew Tessa and Kathy the best. I had been friends with Tessa since we were both about five years old. She had lovely black hair and an interesting, angular face and white teeth; some of her relatives had been actors; she was talented in art and she spoke her mind in an honest way. Kathy came from a large family and had brown hair; her eyes and her mouth worked together when she smiled, and we always felt we could trust her and her kindness.

A letter from what would be our new community had earlier asked that our parents please not drive us to Dubuque. The Sisters wanted to avoid what could always threaten to turn into weeping and the gnashing of teeth at their gates.

Just watch your daughter disappear through the doors of a convent. Try looking down at her feet in black flats walking away from you into the religious life. Better to put her on the train, the Burlington Northern, so that it felt like she was going off to college.

I sat in that cab and smoked two cigarettes at a time.

To be funny.

I thought I was being funny, trying to look frantic to smoke them all up, juggling the two lit cigarettes, Kents, in my ringless fingers. In the end, I would still have plenty of cigarettes left for my taxi driver, who undoubtedly watched us through his rear-view mirror. I felt like a comedian.

We had smoked since freshman year in our all-girls Catholic high school, which was called Our Lady of Peace. We certainly werent allowed to smoke at Our Lady of Peace. But after school some of the bolder of usnot Iwould walk a couple of blocks down Victoria Street to, say, Grand Avenue and step into their boyfriends 55 Oldsmobile 98s or 56 Chevrolets (which action was also not allowed by our school), and within thirty seconds the smoking started. Off they went, Bernadette inhaling, Tom exhaling; Patricia blowing smoke through her nose, Mark grasping the knob on his steering wheel to make a dashing left turn, a louie.

We had been instructed to bring only enough money to get us to the convent, and I must have tried to calculate it before I left home, which was on Goodrich Avenue in Saint Paul: so much for a ham sandwich and a Coke on the train, and maybe a Nut Goodie or a Mounds bar; so much for cab fare and tipthat was it.

And so we handed over that cab fare and that tip and the rest of our cigarettes, and that part was over. The cabdriver thanked us.

We thanked him. It was time, just the way it was time when the curtain went up in the high school plays in which we had acted. Mother Was a Freshman. The Song of Bernadette. The Little World of Don Camillo.

Its time, girls.

We stopped laughing, got out of the cab, and walked up the sidewalk.

Several Sisters were at the door to welcome us. Even before I stepped over the threshold I felt relief from the heat. The motherhouse, I thought, was going to feel good compared to the muggy Iowa summer afternoon.

I had seen the motherhouse before but I had never been inside.

Next page