This eBook edition published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2009 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright Graeme Davis 2009

The moral right of Graeme Davis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 .

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-065-4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Vikings to America

In fourteen hundred and ninety-two

Columbus sailed the ocean blue.

He had three ships and left from Spain:

He sailed through sunshine, wind and rain.

SO goes the school-room jingle, and so most people today perceive the dawn of European exploration and settlement of America. Yet it is not Columbus but the Vikings who should be credited with the first significant European exploration and settlement of America.

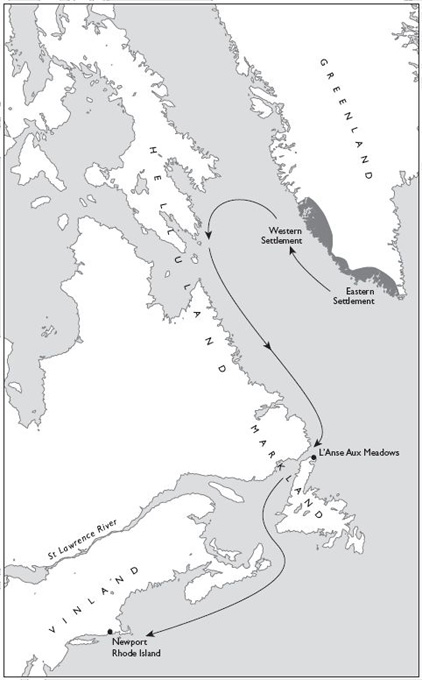

Around five centuries before Columbus, the Vikings both explored and settled in America. The archaeological remains at LAnse aux Meadows in Newfoundland leave no doubt that they established a substantial presence on the American east coast. Today we know for sure that the Vikings were there. Yet in popular perception the story of the Vikings in America remains at the margins of history. As a result the Vikings and their exploration of what they called Vinland is now presented as little more than a footnote in world history. The implicit assumption is that their remarkable achievement had no lasting impact on the history of either Europe or America.

The picture is changing. In recent years academics working in many different disciplines have been finding fragments of evidence which taken together tell a far bigger story of the Vikings in America. This is the story presented here.

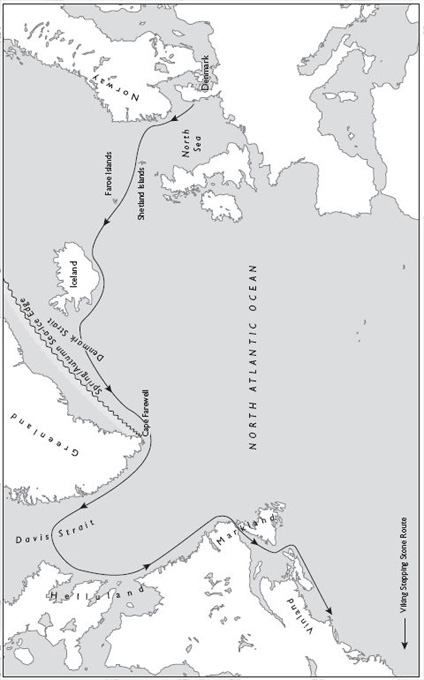

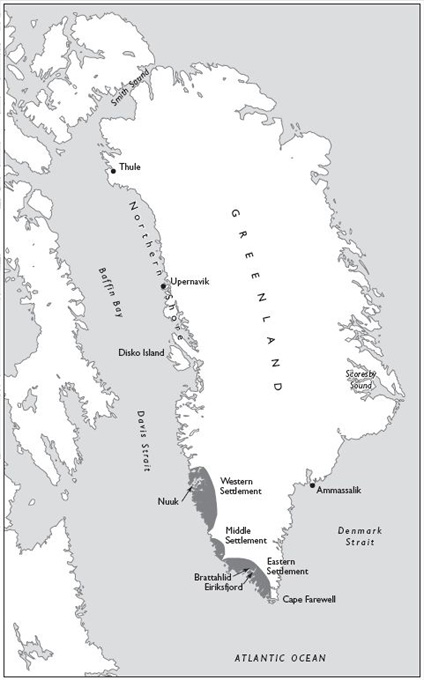

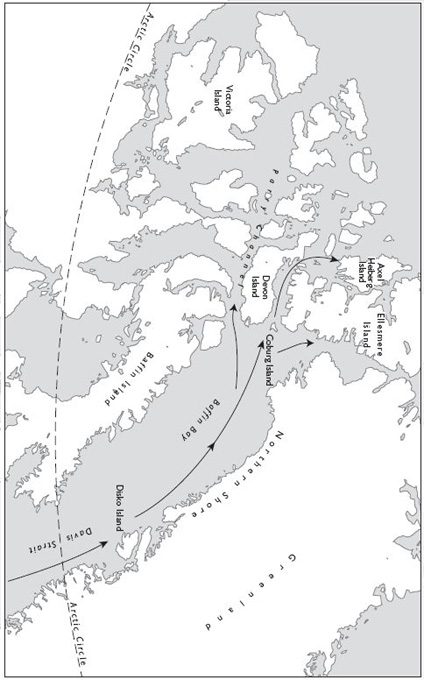

For the Vikings did a lot more than just visit a few places in Newfoundland or elsewhere on the American east coast. From their base in the Viking colony of Greenland itself strictly part of the American continent we now know that the Vikings explored in three different directions. A thousand miles south from Greenland is the archaeological site of LAnse aux Meadows, a staging post on the journey to what they called Vinland, east-coast America. A thousand miles north from Greenland the Vikings reached the High Arctic. Here Viking archaeological remains have been found in some of the most unlikely locations, in lands no-one would have dreamed the Vikings could ever have reached. Today we must accept the evidence of that the Vikings, against all expectations, in fact reached the High Arctic. Furthermore, 1,000 miles west from Greenland in Hudson Bay and its vicinity we have evidence of Viking presence, and can place the Vikings at the centre of the North American continent. Viking Greenland emerges as the starting point for exploration of three widely separated areas of the American continent: the east coast, the far north and Hudson Bay.

The Viking presence in America was no brief interlude, but something that lasted as long as the Viking Greenland colony a little short of 500 years. Most of the voyages to America were made to bring back to Greenland and Europe cargoes of raw materials but some resulted in over-wintering and some in settlement. Today we must accept that the Vikings played a noteworthy role in the exploration and development of America.

Stories of America came back to Europe. Yet for a variety of reasons largely a mix of commercial sensitivity and bad conscience Europe turned its back on these stories. This virtual conspiracy of secrecy is the canvas on which was written the fiction of the Columban discovery of America. Yet at a time when Mediterranean Europe was promoting the Columbus myth, northern Europe, particularly Britain, was demonstrating a continuing tradition of sailing directions that went back to the Viking explorers, as shown in the British search for a north-west passage. Without the Vikings, the post-Columban re-exploration of North America would have been very different in its character.

In researching Vikings in America I found a great mass of firm evidence, but also an almost equal volume of what may best be described as fiction. I have, however, looked at a whole range of doubtful evidence which may or may not give information about Vikings in America. In all cases I have sought to be clear that there are doubts, but also to avoid the temptation to discard theories out of hand. At least some of the disputed materials will, in my view, come to be accepted as reliable.

The most controversial legacy of Viking America presented in this book is that the name America is of Viking origin. The old view that America takes its name from the explorer Amerigo Vespucci is a tired idea now so totally discredited that it cannot be maintained today though still taught in many American schools. It may be that in discarding the Amerigo Vespucci hypothesis we should simply say that we do not know where the name America comes from. Yet we must also note that America is a regular phonological development of a name we know the Vikings used in their Old Norse language for this part of the world. Either the Vikings named America, or by some strange coincidence America gained from an unknown alternative source a name which resembles that used by the Vikings. The Vikings are certainly the first European settlers of America; they may also be the people who named the continent.