Ryan Gingeras

THE LAST DAYS OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Contents

About the Author

Ryan Gingeras is a professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School, California. His previous books include Eternal Dawn: Turkey in the Age of Atatrk and Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire , which was shortlisted for the Rothschild Book Prize in Nationalism and Ethnic Studies and the British-Kuwait Friendship Society Book Prize.

List of Illustrations

Kalusd Srmenyan with fellow officers. (Credit: Yaar Cora) Hseyin Fehmi. (Credit: Trkiye Bankas Kltr Yaynlar) Procession celebrating the opening of the Ottoman parliament, Merzifon, northern Anatolia, December 1908. (Credit: United Church of Christ (UCC), American Research Institute in Turkey (ARIT), SALT Research) Izmir/Smyrna, c. 1922. (Credit: Underwood & Underwood, Library of Congress) Galata Bridge, Istanbul, October 1922. (Credit: Kahn Collection, Archives de la Plante) Talat Pasha delivering a celebratory address on Ottoman Independence Day. (Credit: Resimli Kitap , August/September 1918) Sultan Mehmed VI Vahideddin being driven in his carriage. (Credit: Bibliothque nationale de France) Ships of the Allied fleet firing a salute in the Bosphorus. (Credit: Chronicle/Alamy) Damad Ferid Pasha, Tevfik Pasha and the Ottoman peace delegation in Paris, 1919. (Credit: Bibliothque nationale de France) Local Armenians and French African troops welcome General Henri Gouraud to Mersin. (Credit: Kahn Collection, Archives de la Plante) British troops marching through the streets of Istanbul. (Credit: Bibliothque nationale de France) Protest meeting in Sultanahmet Square, Istanbul, 1919. (Credit: Wikicommons) Mustafa Kemal in the study of his Ankara home, 1921. (Credit: Library of Congress)Open session of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, February 1921. (Credit: Library of Congress) Ankara, late 1922. (Credit: Kahn Collection, Archives de la Plante) Nationalist fighters in Antep. (Credit: Atatrk Kitapl) Armenian women identified as pro-Greek guerrillas in Kirmasti (Mustafakemalpaa). (Credit: Atatrk Kitapl) Muslim Indian migrants ( muhajirun ) marching towards Afghanistan in protest at British treatment of the Ottoman caliph. (Credit: Chronicle/Alamy) Ahmet Anzavur. (Credit: Wikicommons) Advertisement for the film Ravished Armenia , 1919. (Credit: Wikicommons) A village in flames during the Greek rout from western Anatolia, September 1922. (Credit: Bibliothque nationale de France) Refugees fleeing Smyrna, September 1922. (Credit: Library of Congress) Refugees from western Anatolia aided by the American Red Cross. (Credit: Library of Congress) Women inspecting the ruins of the Cihanolu mosque, Aydn. (Credit: Kahn Collection, Archives de la Plante) Nationalist troops parade through Istanbul, November 1922. (Credit: Atatrk Kitapl) Abdlmecid II proceeding to the ceremony to install him as caliph, November 1922. (Credit: Wikicommons) Mehmed VI arrives in exile in Malta, November 1922. (Credit: Wikicommons) Celebration of the fourth anniversary of the liberation of Izmir, September 1926. (Levantine Heritage Foundation) The Turkish Republic and the Ottoman sultanate. Satirical cartoon from the Turkish newspaper Akbaba , 30 October 1924. Desire ( Emel ) bearing the Ottoman coat of arms and the scarlet flag of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. (Credit: Atatrk Kitapl)

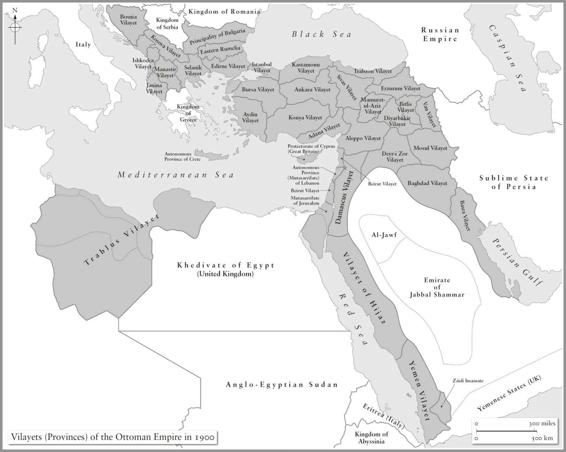

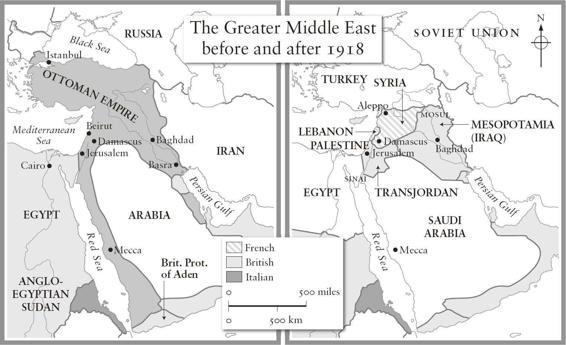

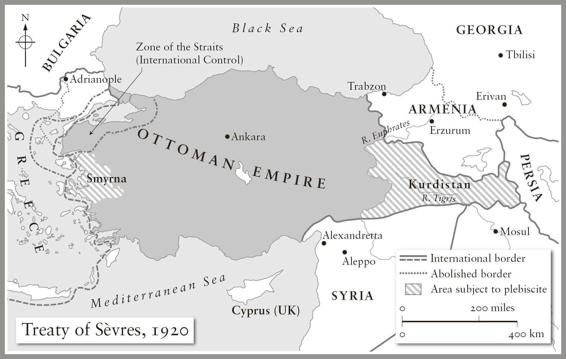

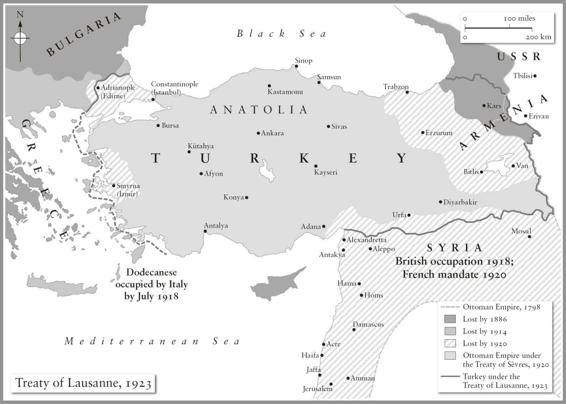

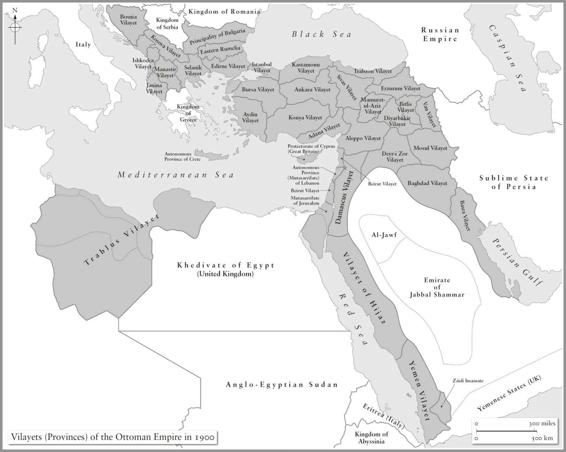

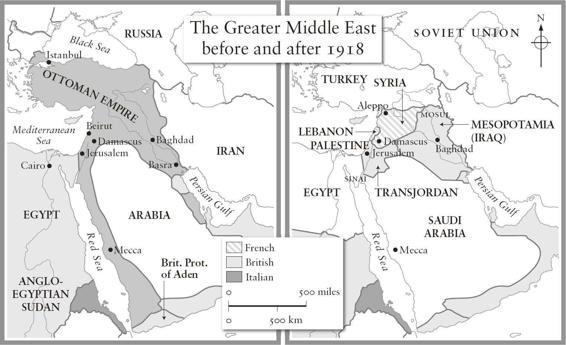

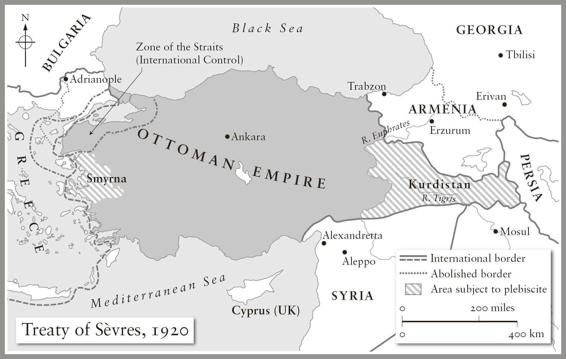

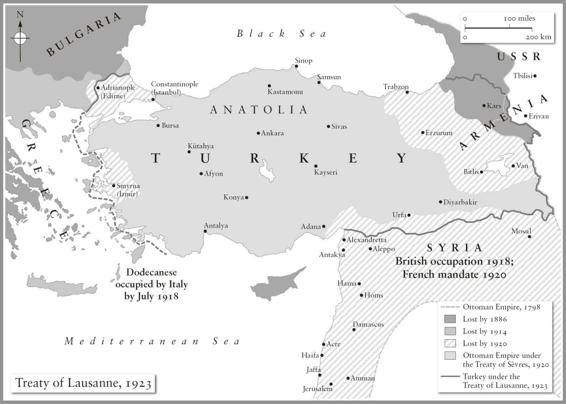

Maps

Introduction

By the last week of October 1918, there was every reason to believe that the Great War had approached its end. News from all points spoke of dramatic events. Since the start of the month, Allied forces had made steady progress all along the line in Flanders. With German troops retreating into Belgium, Kaiser Wilhelm II sanctioned efforts to secure an armistice with the Allies. Erich Ludendorff, who had commanded the German army through much of the fighting, resigned in anger as October came to a close. Although he and other ranking generals stood willing to fight to the bloody end, a different sort of bitterness reverberated through the ranks. Before the month was out, mutinous soldiers took to the streets of Berlin calling for an end to Wilhelms rule. Similar scenes of revolution were unfolding to the south in the Habsburg lands as well. By the 30th, Vienna betrayed signs of insurrection as thousands of demobilized soldiers joined demonstrators demanding the royal familys abdication. Events were moving even faster in Budapest. There, lawmakers had already commenced efforts to break away from the Habsburg crown. As Hungary lurched towards independence, separatism had taken root in Poland, Czechoslovakia and among the south Slavs. In Bulgaria, the least of the Central Powers, political uncertainty reigned. After abandoning the war early in the month, peasants and soldiers rose up outside the capital, Sofia, forcing Tsar Ferdinand to vacate the throne.

It was on 30 October that the Central Powers most eastern member, the Ottoman Empire, conceded its own defeat. Like other members of the alliance, fortune had long deserted the empire on the battlefield. Earlier in September, British forces had broken through Ottoman defenses outside Nablus in Palestine. Over the following weeks, the

And yet, with the signing of an armistice at the end of October, the imperial government offered no signs that it feared revolution or dissolution. Speaking before the press the day after the empires surrender, Istanbuls chief negotiator declared that he returned to the capital with joy and pride, not sadness. Our countrys rights, he proclaimed, and the future of the Sultanate have been wholly saved as a result of the armistice concluded. The British delegation had publicly avowed that they did not seek to destroy the nation. Nor, he assured journalists, would a foreign army come to occupy the capital. Yes, he exclaimed, the armistice we have concluded is beyond our hopes.

Very few would retain such optimism as the days passed. Within a week of the armistice, the sitting government dissolved itself in consultation with the sultan. The resignation of the grand vezir, the countrys highest civilian official, came as the empires only political party agreed to disband. After a decade in power, the collapse of the reigning Committee of Union and Progress tore at the very fabric of the Ottoman political establishment. The iron rule of the CUP or Young Turks, as they were so often called had long polarized both state and society. During its ten years in power, the CUP had fought and lost three wars and had driven all dissent underground. Young Turk leaders assumed office in 1908 championing the principles of liberty and equality under the law. A decade later, the CUP had methodically disenfranchised vast numbers of citizens, most of them Christians. Hundreds of thousands were killed in the process. With the party now gone, and its leaders driven into exile, doubt and animosity weighed heavily over the capital. Contrary to earlier assertions, the first contingents of an occupying army arrived in Istanbul in mid-November. The prospect of the capital under occupation, as one senior official remembered, exposed a deep rift within society as a whole. In Beyolu, the capitals historic foreign quarter, the appearance of British and French ships docked offshore was greeted with wild excitement. All the houses, the shops, hotels and restaurants were decked out like it was a grand celebration, he remembered. Rather than rue the coming occupation, locals there, most of them Christians, embraced the British, French and Greek presence as a moment of redemption. The mood across town, however, could not have been more somber. In predominately Muslim neighborhoods such as Eminn, Topkap and Eyp, the streets were decidedly dark and empty. Save for the meowing of hungry cats and the hopeless barking of stray dogs, one rarely heard voices. Amid wet weather and grieving families, the official, and others like him, were left trembling with a sense of catastrophe and mourning.

Next page