The Sultans FleetTo my grandchildren Jack, Juliet, Tabitha, Astrid, Avalyn, Avery, Caspian, and Owen

The Sultans Fleet

Seafarers of the Ottoman Empire

Christine Isom-Verhaaren

Contents

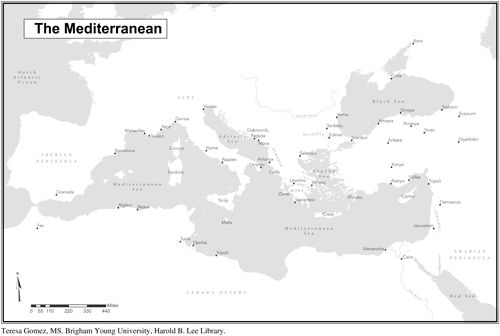

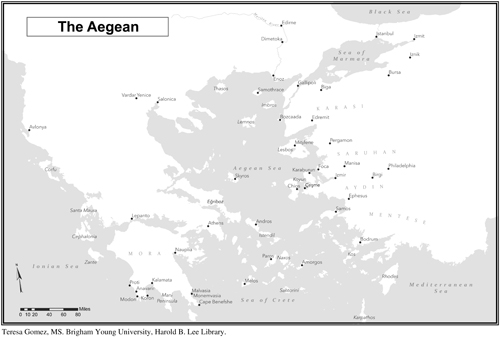

When several years ago I first contemplated writing a history of the Ottoman navy covering multiple centuries, I had no concept of how difficult this project would be to complete. I blithely left my comfort zone of researching naval topics during the sixteenth century and dove into exploring a very different empire both in the fourteenth and in the seventeenth centuries. Additionally, while studying Ottoman seafarers, I have also pursued interconnected topics; consequently, I have benefited from many contacts with a variety of people. I fondly remember talking with many of the following at the ARIT hostel in Istanbul, or at conferences in a variety of locations. I thank the following for providing assistance: Virginia Aksan, Nabil al-Takriti, Palmira Brummett, Mark Choate, John Curry, Eric Dursteler, Suraiya Faroqhi, Dan Goffman, Emrah Safa Gurkan, Jane Hathaway, Julia Landweber, Jonathan McCollum, Murat Cem Menguc, Ramazan Hakki Oztan, Leslie Peirce, Kent Schull, Amy Singer, Will Smiley, Michael Talbot, Malissa Taylor, Joshua White, Gillian Weiss, and Fariba Zarinebaf. I thank Teresa Gomez of the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University who produced the maps for this book. I also want to thank Amaia Kennedy and David Patton, two student assistants at BYU who completed valuable tasks for me. In addition, I wish to thank my editors at IB Tauris and Bloomsbury, Joanna Godfrey and Rory Gormley. Special thanks are due to Svat Soucek who encouraged me to continue writing about the Ottoman navy because he believed many more studies were needed on naval history, and Linda Darling who has been a willing listener to many discussions about the navy over the years. I especially wish to thank my family, especially my husband Bruce, who recently traveled to Rhodes and Kos with me, and to my children Catharine, Christopher, and Nathaniel who have heard a great deal about this project for many years.

The Ottoman navy provided an essential component in facilitating Ottoman expansion from the reign of Orhan in the fourteenth through the early eighteenth centuries. Nothing concerning naval forces is known from the period of Osman; however, for every succeeding Ottoman ruler, the status of their fleet impacted all their other activities, especially including expansion by their territorial forces. This being the case, it is remarkable that most general histories of the Ottoman Empire devote little attention to naval affairs and then usually as a brief passing mention. A paucity of sources for the earliest period is a possible explanation, but that has not deterred historians from writing about land-based military expansion during all periods. The few historical surveys of Ottoman naval forces that have been written by Ottoman historians omit the fourteenth century and ignore the Ottomans Turkish rivals who excelled in seafaring before the Ottomans expanded navally.

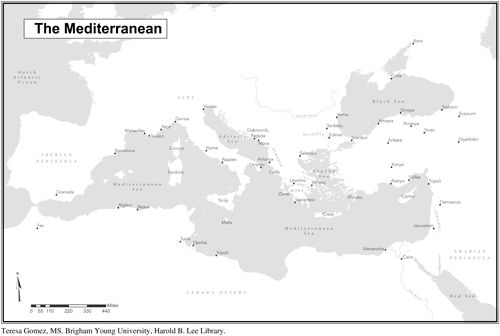

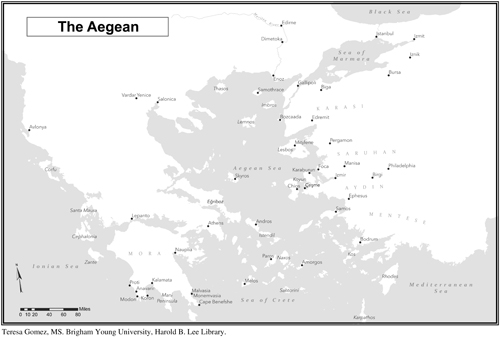

Turks arrived in Anatolia after the battle of Manzikert in 1071 soon expanding to the west until their leaders established their capital at Iznik (Nicea) on the doorstep of the Byzantine fabled capital, Istanbul (Constantinople). Their impact was great, leading to this region eventually becoming Turkish speaking and ruled by a Turkish dynasty, the Seljuks of Rum. The Byzantine emperor begged assistance from his Christian coreligionists in the west under the Pope of Rome to remove the Turks from his vicinity and requested some mercenary soldiers to enter his service to defeat them. Instead this proposal led to the crusades, bringing Latins (Roman Catholics from Europe) in greater numbers into his domains. The Turks became a permanent fixture in Anatolia and the Latins eventually conquered Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade and established a Latin Empire there, and their Byzantine rivals retreated to Iznik. In 1261, the Byzantines regained Constantinople putting an end to the Latin Empire, but not to the many Latin lordships in the Balkans, Anatolia, and on Aegean islands. In the eleventh through thirteenth centuries, the descendants of the original Turks who had spread throughout Anatolia made little headway in establishing a presence in coastal cities of the Aegean, Black, or Mediterranean Seas. However, during the period that the Byzantines regained Constantinople new waves of Turkish migration swept across Anatolia and these Turkish beys (lords) founded petty states ( beyliks ) throughout Anatolia, including in maritime regions. These Turks began to challenge Byzantines and Latins for control of the surrounding seas.

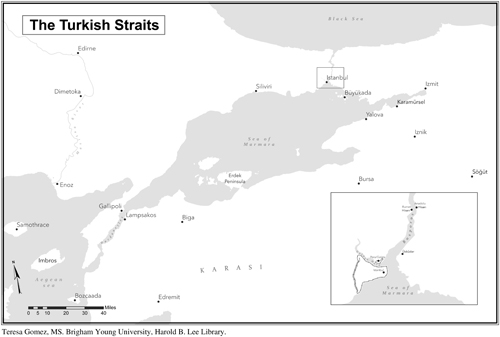

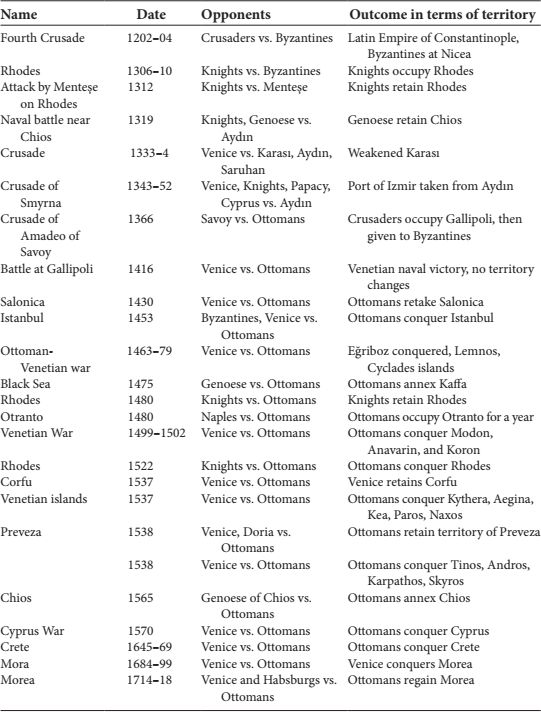

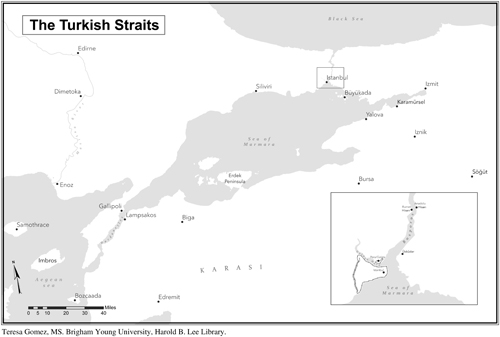

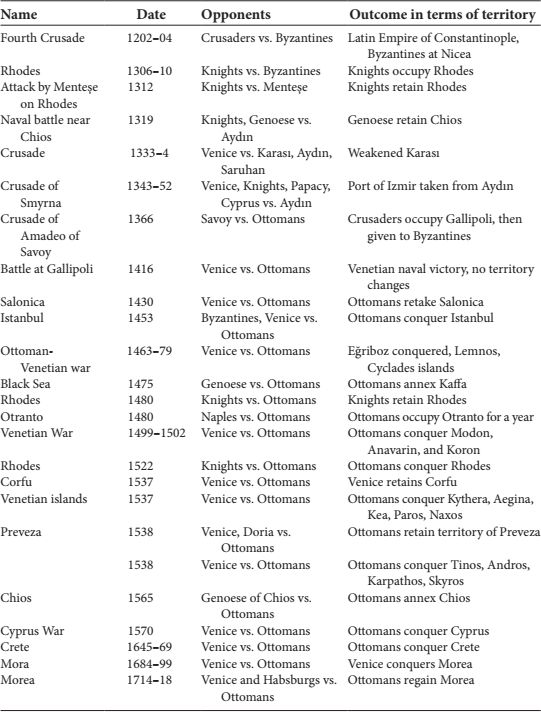

This book traces the contest between Turks, Byzantines, and Latins for rule of maritime lands and seas that eventually became core territories and seas of the Ottoman Empire (see Table 1). For unlike the previous Turkish rulers of Anatolia, most notably the Seljuks, the Ottoman sultans considered themselves rulers of lands and seas: Mehmed II (d. 1481) after he became known as the Conqueror because he had conquered Istanbul claimed to rule the two lands and the two seas: Anatolia and the Balkans and the Aegean and the Black Seas. This conquest demanded naval power to secure because without at least partial control of the Aegean and Black Seas his prize would always be endangered. Thus, whenever Ottoman naval power weakened over the centuries the security of Istanbul was threatened. This contest for control of especially the Aegean is seen through the exploits of the many Turkish, then solely Ottoman seafarers who served Ottoman sultans in the process of transforming these valuable maritime locations into possessions of the Ottoman dynasty. The Turkish Straits, as they are officially known, consist of the Dardanelles to the South, and the Bosporus to the north, which the city of Istanbul straddles today. The book traces the exploits of the seafarers during the middle centuries of Turkish naval expansion, from approximately 1300, when several Turkish beyliks were established on the Aegean coast, until 1718 when the Ottomans defeated Venice in a final war between them and regained key Ottoman maritime territories. The contest is viewed primarily through narrative sources produced by Ottoman authors who celebrated the victories and mourned the defeats of Turkish seafarers.

Table 1 Naval Conflicts between Turks, Byzantines, and Western Europeans with territorial outcomes

Ottoman naval encounters with their competitors have given rise to sources written by authors sympathetic to the Ottomans and those who favored their opponents and each type of source has its strength and weaknesses depending on the interests of the historian. Byzantine and Latin sources are valuable, but they only present the non-Turkish, then non-Ottoman, perspective on the naval conflicts described in this book. These sources are often of crucial importance in delineating events, but they frequently obscure an Ottoman understanding of the conflict. Sometimes sources produced by outsiders include factual errors, such as claiming that Mezemorta led the Ottoman fleet in the Mediterranean in 1690, when in fact he was leading naval forces on the Danube that year. Of greater significance, because they are more difficult to counter, are biased views of the motivations of Ottoman seafarers. For example, during the Morean War, each side claimed that the other fled from battles and was unwilling to fight. Sources written from the perspective of Ottoman participants might explain why they fought in some instances and not in others, without it appearing that they were inherently cowardly rather than making rational decisions based on their ability to defeat the enemy in a given encounter. Reasonable caution by ones own forces can be portrayed as cowardice in an enemy; however, such judgments should be questioned. There were instances of Ottoman cowardice, but they should not be confused with occasions of reasonable choices to retreat until a more favorable opportunity to defeat the enemy presented itself. Thus, understanding the motivations of the Ottoman actors to the extent possible requires favoring Ottoman sources.