This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1962 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

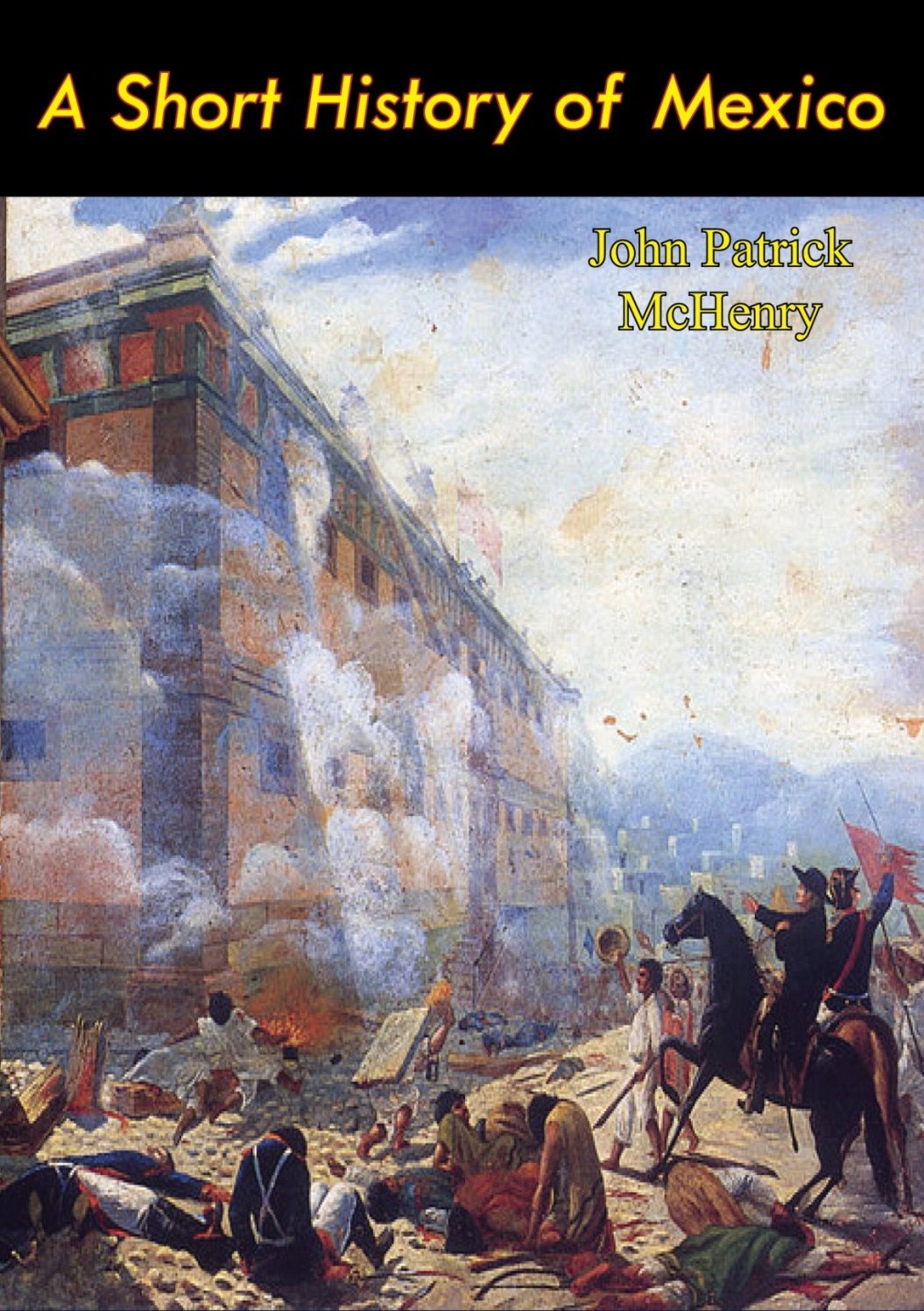

A SHORT HISTORY OF MEXICO

BY

J. PATRICK McHENRY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

TO MY MOTHER AND FATHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Several people have helped, with their suggestions and advice, to write certain chapters of this book. I am especially indebted to Mr. Crispin Tickell for his valuable comments on the first three chapters covering ancient Mexico and the conquest; to Miguel Diaz, who contributed information on Iturbide and the post-revolutionary period; and to Professor Jos Mireles Malpica for his kindness in checking the manuscript. And last but not least, to my wife, whose assistance and encouragement was constant throughout.

A SHORT GLOSSARY

CACIQUEOriginally an Indian word meaning the Indian chief of a village, it is now used by Mexican journalists to mean political bosses in rural areas who manipulate businesses for their own personal profit.

CAMPESINOAn agrarian; a country person.

CREOLEThe Spanish translation is criollo , which in Mexico means a Mexican of pure Spanish blood.

EJIDOSIn colonial times these were communal lands for threshing and grazing. Since the revolution this word has meant tracts of land given by the government to small farmers.

EJIDARIOSFarmers who work the ejidos .

GACHUPINESDerogatory nickname for Spaniards living in Mexico.

HACENDADOThe owner of a hacienda.

HACIENDAStems from the verb hacer , to make. They were places where refined sugar was made from sugar cane or pure metals were extracted from ores (gold and silver). Formerly they provided work for an entire Mexican village; today they are massive, moss-covered ruins, relics of past times.

MULATTOA person with part Negro and part Spanish blood.

PENINSULARESSpaniards.

PULQUEA milky, intoxicating drink made from the sap of the maguey plant.

TAMANESIndians who were professional carriers. In pre-Columbian times they did the work of horses.

ZAMBOSA person with part Negro and part Indian blood.

ZCALOThe principal plaza of a city or town where usually the main cathedral and municipal buildings are located.

MAPS

I. The Route of Hernando Corts

II. Mexicos Loss of Territory during the Nineteenth Century

III. Mexico Today, Showing Towns Mentioned in the Text

A SHORT HISTORY OF MEXICO

CHAPTER ONE 10,000 B.C.A.D. 1518

When Christopher Columbus first sighted land in the Caribbean, he was certain he had reached the East Indies. It was only logical then that the golden-skinned natives he found on the islands should be called Indians. His logic was unquestionably sound, but his calculations were a whole hemisphere off. By the time he realized the colossal magnitude of his error, the name for natives in America had been irrevocably fixed and the misnomer Indian comes down to us as an example of how logic can lead to absurdities.

What Columbus discovered, of course, were islands of America where flourished a culture whose principal center was as large (and as beautiful) as Venice, whose philosophy and mathematics contained some precepts as profound as those of the Greeks, and whose knowledge of astronomy was as accurate as that of European scientists. It is not likely that members of this culture would admit that Columbus had discovered anything. How their culture began and grew, what their heritage was, what ancestry they had, or how, indeed, man came to be in America at all, is not known for certain, since no written history (as we understand history) of pre-Columbian cultures in America exists.

The history that does exist has been logically recreated from crumbling pyramids, fading murals, broken pots, and strange stone carvings. La Historia Universal de las Cosas de Nueva Espaa ( The Universal History of the Things of New Spain ), a work by a sixteenth-century Spanish monk named father Bernardino de Sahagn, is the most important record we have concerning ancient Mexico, but it is so full of fantastic myths and legends that one needs intuition as well as science to understand it. For nearly three centuries this invaluable work gathered dust in obscure places until, early in the nineteenth century, an Englishman named Lord Kingsborough brought it to light in propounding his theory that Mexico, like Egypt, had been a distant outpost of the long-sunk continent Atlantis. Though his theory caused no great stir in scientific circles, the mass of material he gathered to support it was eagerly received by young men pioneering in a new branch of science called archaeology. Since then, archaeologists, geologists, and ethnologists, picking over the ruins of ancient Indian cities, have produced a myriad of artifacts on which the pre-Columbian history of Mexico has been constructed. In general their findings corroborate or throw new light on the writings of that early Spanish monk.

The remarks in this chapter are a kind of synthesis of the latest theories accepted by archaeologists and historians. Although presented in a matter-of-fact way, the story told here is far from certain and is liable to change with new discoveries by archaeologists. Their finds are incomparably more valuable than theories, for theories derive from logic, and logic, as we have seen in the case of Columbus, can lead to hopeless confusion.

In 10,000 B.C. that part of the North American continent now known as Mexico was covered with dense jungles in the lowlands, forests and patches of grassy plains in the highlands, and, in the north, deserts. The central plateau was humid and rich in vegetation and was visited frequently by groups of longhaired mammoths seeking succulent plants. From the trees they were scolded by flocks of colorful parrots. On the windy plains grazed herds of large bison, and groups of bounding antelope were common. There were also elephants. In damp places giant armadillos scratched for food. In dry places roamed the haughty camel. A species of horse, now extinct, ran wild in the highlands. And the rarest sight of all was man.

For over a century it had been suspected that man had inhabited Mexico as early as 10,000 B.C., but it wasnt until 1945 that this was decisively proved. Workmen digging foundations for a hospital in Tepexpan, a tiny village on the road to Laredo outside Mexico City, unearthed the remains of a giant-sized mammoth near whose skull was found a crudely made spearhead. The eminent geologist and archaeologist called in to appraise the discovery found (with more digging) a few yards away and in the same earth stratumcalculated at 800010,000 B.C. by carbon testsa human skeleton. A careful examination of his skull revealed that he was not a Neanderthal or Java man, as paleontologists had hoped, but a Homo sapiens. Frederick Peterson states, Alive, in modern clothes, and walking about the streets of Mexico City, he would excite no comment whatsoever.

Next page