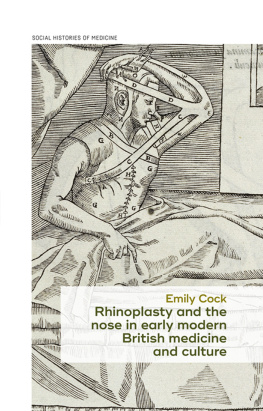

Rhinoplasty and the nose in early modern British medicine and culture

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF MEDICINE

Series editors: David Cantor and Keir Waddington

Social Histories of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness and medicine, from prehistory to the present, in every part of the world. The series covers the circumstances that promote health or illness, the ways in which people experience and explain such conditions, and what, practically, they do about them. Practitioners of all approaches to health and healing come within its scope, as do their ideas, beliefs, and practices, and the social, economic and cultural contexts in which they operate. Methodologically, the series welcomes relevant studies in social, economic, cultural, and intellectual history, as well as approaches derived from other disciplines in the arts, sciences, social sciences and humanities. The series is a collaboration between Manchester University Press and the Society for the Social History of Medicine.

Previously published

The metamorphosis of autism BonnieEvans

Payment and philanthropy in British healthcare, 191848 George CampbellGosling

The politics of vaccination Edited byChristineHolmberg,StuartBlumeandPaulGreenough

Leprosy and colonialism StephenSnelders

Medical misadventure in an age of professionalization, 17801890 AlannahTomkins

Conserving health in early modern culture Edited bySandraCavalloandTessaStorey

Migrant architects of the NHS Julian M.Simpson

Mediterranean quarantines, 17501914 Edited byJohnChircopandFrancisco JavierMartnez

Sickness, medical welfare and the English poor, 17501834 StevenKing

Medical societies and scientific culture in nineteenth-century Belgium JorisVandendriessche

Managing diabetes, managing medicine Martin D.Moore

Vaccinating Britain GarethMillward

Madness on trial James E.Moran

Early modern Ireland and the world of medicine Edited byJohnCunningham

Feeling the strain JillKirby

RHINOPLASTY AND THE NOSE IN EARLY MODERN BRITISH MEDICINE AND CULTURE

EmilyCock

Manchester University Press

Copyright Emily Cock 2019

The right of Emily Cock to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN978 1 5261 3716 6hardback

First published 2019

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cover image: Gaspare Tagliacozzi, De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem (Venice: 1597), Wellcome Collection, CC BY.

Cover design: riverdesignbooks.com

Typeset

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

This book has been completed piecemeal across and alongside a number of short-term positions, across the world, inside and outside academia. I am as thankful for the enthusiasm, encouragement, intermittent nose queries, and suggestions of non-academic colleagues at the University of Adelaide Contact Centre and Wordsworth Museum, as for those of students and staff at Adelaide, Swansea, Winchester, and Cardiff Universities. I would like to acknowledge support from the Bill Cowan Fellowship at the Barr Smith Library (Adelaide), the International Centre for Jefferson Studies (Monticello), and the Wellcome Trust. The Chawton House Library very kindly extended my residence when I found myself stranded, and for this I am eternally grateful. The final push has been facilitated by an Early Career Fellowship from the Leverhulme Trust.

I am immensely obliged to the special collections librarians who have assisted me in person and by email with information or scans of their holdings. It has not been possible to include every copy of Tagliacozzi or Read in this book, and I offer apologies to anyone whose collections have been neglected, or for which I was not able to solve the provenance mysteries. I share any disappointment!

Heather Kerr provided generous and invaluable encouragement and guidance over many years, and is loved and missed. I would also like to thank Lucy Potter and Harriette Andreadis for their constructive early suggestions. The project has been immeasurably challenged and improved by working with Patricia Skinner and the Effaced from History network, including Changing Faces. The anonymous reviewers from Manchester University Press, and those of related earlier articles and conference papers, have also provided very useful suggestions. Material has previously appeared in Lead[ing] em by the Nose into publick Shame and Derision: Gaspare Tagliacozzi, Alexander Read, and the Lost History of Plastic Surgery, 16001800 Social History of Medicine 28:1 (2015), pp 121, and Off Dropped the Sympathetic Snout: Shame, Sympathy, and Plastic Surgery at the Beginning of the Long Eighteenth Century, in David Lemmings, Robert Phiddian, and Heather Kerr (eds) Passions, Sympathy and Print Culture: Public Opinion and Emotional Authenticity in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp 145164, and is reproduced with permission.

My parents, Barry and Merren, have supported me with love and good humour. I have subjected innumerable friends, choirs, colleagues, and housemates to nose stories and writing trouble, and offer thanks and apologies for the patience, as well as not infrequent food and a bed. Special mention to Kirsty, Amy, Fiona, Krystal, Caroline, Kelli, Chelsea, Maree, Trish, Catherine, Gordon, and Jordan. The book is dedicated to my grandmothers, Maurveen and Ivy.

The nose is the most prominent part of the most prominent part of the body. Concern over the violated or deformed nose and its impact on the life of the individual was shared by surgeons and the wider community in early modern Britain, and should perhaps have led to axiomatic support for medical interventions that could restore the injured or even missing nose to its expected form and function. Such a procedure was meticulously detailed by the Bolognese surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (15451599) in De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem (On the surgery of mutilations through grafting, (Venice: 1597)). Tagliacozzi's rhinoplasty procedure lifted a flap of skin from the patient's upper arm to reconstruct the nose, and is now so well known it forms the logo of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, with Tagliacozzi heralded as the father of plastic surgery. But histories of plastic surgery maintain that after Tagliacozzi's death his procedure disappeared from medical knowledge for the following two centuries. This is incorrect. It is likely that Tagliacozzi's procedure was never practised in early modern Britain, but it was a subject of medical and popular debate, and his book remained available. Knowledge of the operation was also accompanied by medical misunderstanding and poetic satires that said that the noses were constructed from skin or flesh taken, or even bought, from another person, and that they would ultimately drop off. This popular iteration became a diversely applied metaphor that trickled from Britain to the rest of the world, drawing rhinoplasty into the history of transplantation, affecting Tagliacozzi's and nasal surgery's reputations into the twentieth century, and endowing nose reconstruction with a cultural burden far beyond expectations.