2004 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Minion type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

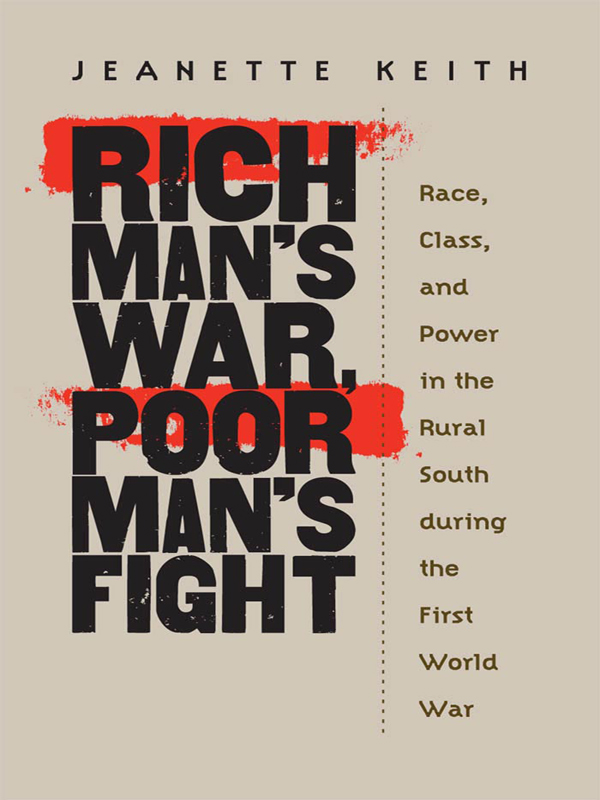

Keith, Jeanette.

Rich mans war, poor mans fight : race, class, and power in the rural South during the first world war / by Jeanette Keith.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8078-2897-1 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-8078-5562-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

eISBN : 9780807875896

1. World War, 19141918Protest movementsSouthern States. 2. World War, 19141918Draft resistersSouthern States. 3. Southern StatesRace relations. 4. Southern StatesSocial conditions18651945. 5. Social classesSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 6. Southern StatesRural conditions. 7. FarmersSouthern StatesPolitical activityHistory20th century. 8. DissentersSouthern StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

D639.P77K45 2004

940.3'16dc22

2004003685

A portion of this book appeared earlier, in somewhat different form, in The Politics of Southern Draft Resistance, 19171918: Class, Race and Conscription in the Rural South, Journal of American History 87 (March 2001): 133561, and is reprinted here with the permission of the Organization of American Historians.

cloth 08 07 06 05 04 5 4 3 2 1

paper 08 07 06 05 04 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

An American president leads the nation into an unpopular war with a distant enemy. He says that the United States is fighting for democracy and freedom, but his critics suggest that the war is being fought to benefit select economic interests. Major national media follow the administration party line, saturating the nation with prowar propaganda, but many people remain unconvinced. Frightened of potential terrorist attacks from the enemy, Congress passes laws penalizing dissent. Authorities squelch antiwar protests, sending scores of dissidents to jail. People who oppose the war learn to lower their voices in public, while self-proclaimed patriots demand total loyalty not only to our boys overseas but to the President. People who fail to conform lose their jobs and sometimes their liberty. Americans face questions about power and politics, propaganda and the manipulation of public opinion, secrecy and surveillance.

This was the state of affairs in the United States in 1917. In this book, I explore the development of dissent during World War I in a most unexpected place, the rural South, where ordinary black and white farmers proved that, despite strident propaganda and punitive laws, American citizens could yet maintain minds and opinions of their own.

MY RESEARCH into rural southern antiwar and antidraft dissent was funded by two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a summer stipend and a yearlong Grant for College Teachers. I received travel grants from the American Philosophical Society and from the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education Faculty Development Fund. Bloomsburg University awarded me a sabbatical, which I spent at Yale University, under the auspices of the Agrarian Studies Program.

Among the many people I wish to thank are K. Walter Hickel; Pete Daniel; Crandall Shifflett; Hal Barron; Kriste Lindenmeyer; Jack Kirby; Susan Stemont; Paul Freedman; Mary Neth; Kay Mansfield; James C. Scott; Leah Porter; Michael Casey; Ben Johnson; Anastatia Sims; Nancy Gentile Ford; Harold Forsythe; Glenda Gilmore and her graduate students in American studies and history at Yale; my colleagues at the Agrarian Studies Program, especially Cindy Hahamovitch and Scott Nelson; Mitch Yockelson at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland; Wayne Moore and the Tennessee State Library and Archives staff; and the professional and helpful staff members of the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale, the Memphis and Shelby County Public Library, the Tennessee State Library and Archives, the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, the National Archives and Record Division at East Point, Georgia, and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Some of the research presented here was previously published in the Journal of American History. I thank the Journals reviewers (especially Gaines Foster and David Kennedy) and staff, especially the editor, David Nord, for astute and helpful criticism. Thanks to the Organization of American Historians for their reprint permission. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for the Journal of Southern History who considered a previous draft of the material presented here on surveillance in the rural South. I learned a great deal from their critique.

Here at Bloomsburg University, I am especially indebted to my colleagues in the Department of History. Our department chair, William Hudon, has been consistently supportive of this project. Joyce Bielen, our secretary, read manuscripts and checked figures, as did Mike Yoder, one of our student workers. I owe special thanks to Michael Hickey, who has heard more about the U.S. draft during World War I than any historian of Russia will ever need to know. Michael provided materials and insights about the topic of surveillance that helped me enlarge my perspective on that issue. In addition, he and James Matta, currently serving as the dean of graduate studies at Bloomsburg, taught me how to write grants; much thanks.

At the University of North Carolina Press, Chuck Grench has been most supportive of this project. Thanks also to Amanda McMillan, Ron Maner, and John Wilson: great people to work with.

Finally, I am grateful to my husband, Tony Allen, without whose help, support, and confidence this work would never have been completed. To him, this book is dedicated.

Introduction

In the spring of 1918, the sheriff of DeKalb County, Tennessee, went up into the hills to bring out John Smith, a deserter from the U.S. Army. Drafted in1917 for service in the First World War, Smith had come home on leave in March and had failed to return to camp. Smith, his wife, and their children lived with Smiths parents. Other deserters throughout the South fought sheriffs, local posses, Texas Rangers, and even federal troops rather than return to the army, but Smith offered no resistance. As the sheriff took him away, Smiths parents made their own protest: the screams of the old people could be heard for some distance.

The historical record does not tell us much about John Smith, just that he was a deserter, a husband, a father, and a son and that his family desperately wanted him to stay home. But it is possible to use Smith, with his emblematic Everymans name, as a way of entering into a rarely explored aspect of the history of the World War I home front: resistance to the war in the rural South. The South had many slackers, to use the term of the times, from deserters like Smith, to draft evaders, to people who cooperated reluctantly, if at all, with wartime mobilization and security measures. Although southern slackers also lived in suburbs and cities, federal and state authorities at the time, and historians since, discovered most resistance in the countryside. Small-town businessmen and their wives, charged with mobilizing the population for war, sometimes found that their mandate evaporated at the end of the paved roads. Country women refused to register for war work. Backwoods preachers condemned war. In rural communities, neighbors sheltered deserters and warned them of approaching federal agents.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.