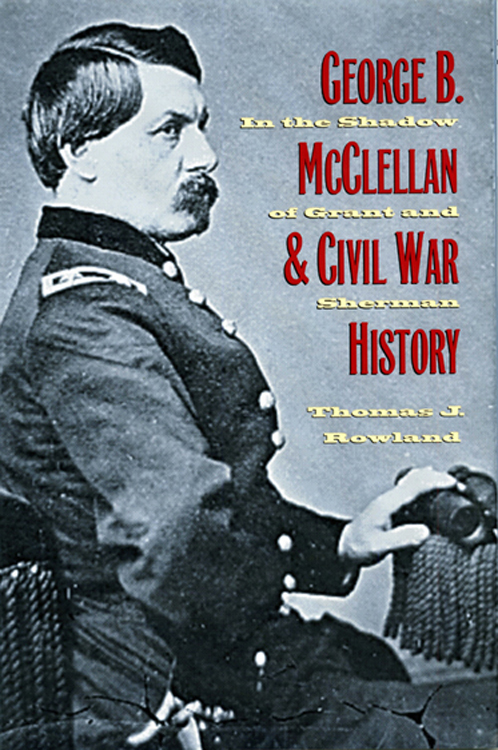

George B. McClellan AND CIVIL WAR HISTORY

1998 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-13967

ISBN 0-87338-603-5

Manufactured in the United States of America

04 03 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rowland, Thomas J., 1952

George B. McClellan and Civil War history : in the shadow of Grant

and Sherman / Thomas J. Rowland.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-603-5 (alk. paper)

1. McClellan, George Brinton, 18261885Military leadership.

2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Campaigns.

3. Command of troopsHistory19th century. I. Title.

E467.1.M2R69 1998

973.7'3'092dc21 98-13967

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

A PERSISTENT QUESTION THAT HAS HAUNTED ME FROM THE first day I contemplated writing about George B. McClellan, up to the very moment I write this sentence, is whether the literature really needs another book about this man. Despite some impressive evidence to the contrary, I have assured myself that it does. The first day I refer to probably goes back to my freshmen year at college in 1970. Since that time, this project has undergone many staggering, fitful starts and stops. Aiding and abetting its forward progress was the lingering puzzlement over how a general who was so talented and filled with so much promise ended up as such a miserable fizzle. The interruptions in the project were easier to understand. Throughout this period, one study after another has virtually codified the thesis that McClellan proved to be a wretched species of Civil War commander, unworthy of anything but additional condemnation. More discouragement came in the form of casual conversations with friends who possessed but a thumbnail sketch of Civil War familiarity. At the very mention of McClellans name, a visage of contempt generally crept over their otherwise benevolent gazes, or worse, they mimed sticking their fingers down their throats. Both were clear, confirming signs of just how ingrained in the popular culture was McClellans infamous repute. For a relative novice in the field, the commanding verdicts of acclaimed historians and the public at large made the prospect of voicing any dissenting opinions a most daunting one. At any rate, I kept coming back to the puzzle and eventually came to believe that more could be said about it.

The study of George B. McClellan that follows takes its form from my conviction that another standard biography or campaign study would serve no useful purpose. The literature is replete with such works. What was needed, in my opinion, was an analytical review of the literature itself. The format of this book, then, is many things but none of them exclusively. It contains biographical and campaign narrative elements synthesized from the excellent studies already written. In undertaking a review of the existing literature it becomes a historiographical work, thus the obvious reliance upon secondary source material. And it is revisionist to the extent that it both challenges well-established Civil War doctrine and suggests alternative mechanisms of reinterpretation. More precisely, I wanted to examine the literature that emerged in the last half century, for it is here that the consensus opinion of McClellan has taken shape. And it is here that we find the evolution of McClellan as a seriously flawed general and individual. The writers of this period, whom I will refer to as Unionist historians,1 have thoroughly dominated the academic evaluation of McClellans Civil War career and have directly influenced the popular perception in the process.

The complete domination of the Unionist interpretation with respect to any analysis of Civil War commanders is one of the basic assumptions of the study. The cornerstone of this interpretation is a generally unreserved approval of the efforts of Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Abraham Lincoln in saving the Union. The waning fortunes for rescuing the Union from utter dissolution were not reversed until the exclusive partnership of those three men was forged and made operational in the spring of 1864. Consequently, any and all efforts that preceded that climactic moment in the history of the war are deemed futile. Based upon this inviolable conviction, the Civil War leadership is ranked. And in this contextual framework, George B. McClellan is so completely overshadowed by Grant and Sherman as to practically ensure his receiving a very low grade.

I have long been uncomfortable with both the assumptions of the Unionist interpretation and the consequences it has had for the McClellan legacy. One of the sources of this discomfort has been that no account has been taken of the contextual differences that existed in fighting the war in 18611862, as opposed to 18641865. After all, it was not until Grant came east in 1864, leaving his Western command to Sherman, that both of their reputations received the acclaim that has enshrined them in the ranks of the wars greatest commanders. It seemed to me that there were material differences in the relative strengths of the Union and Confederate military machines between the time McClellan held the highest command in the North and when Grant and Sherman assumed control. The question as to why Grants eastern predecessors found success so elusive has never been fully answered. Was it merely, or even principally, a question of leadership, or did other factors play a more significant role?

That is the question upon which this study revolves. It is, in part, an exploration into the mythic Grant and Sherman. To a great extent, this investigation will help explain why McClellan has been discarded into the scrap heap of failed commanders, for when all is said and done, he was the most conspicuous and formidable personality in the East before Grant arrived. It offers another context for understanding why the North experienced so much disappointment in the early years of the war and how that adverse direction was reversed in the later years. In the process, it hopes to shorten the shadows Grant and Sherman have cast over McClellan without necessarily elevating the latters stock at the expense of the other two.

This final caveat probably needs amplification and clarification. At various times, the study will appear unduly harsh in its evaluation of Grant, Sherman, and at times, Lincoln. No intentional attempt was made to create a strawperson(s) scenario, in which Grant, Sherman, and even Lincoln are diminished in order to resurrect and elevate McClellans career. I adopt this approach only when it seems that McClellans critics have singled him out for flaws that were shared, and even exceeded, by many other commanders during the war. Even though I would argue that the unqualified ranking of Civil War commanders is a flawed process itself, I would still feel compelled to rank Grant and Sherman as the foremost military commanders in the North during the Civil War. If for no other reason, their success is a difficult thing to argue against. Consequently, the one thing this study does not undertake is the rehabilitation of George B. McClellans reputation to the point of claiming he was a great commander. His lack of success militates against any such undertaking. But while I agree with those who suggest that McClellan might have been better suited for the position that Henry Halleck held during the war, I do not view him, despite his record as a field commander, as an abject failure.