Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Race Over Party

MILLINGTON W. BERGESON-LOCKWOOD

Race Over Party

Black Politics and Partisanship in Late Nineteenth-Century Boston

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the Authors Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2018 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arno Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bergeson-Lockwood, Millington W., author.

Title: Race over party : black politics and partisanship in late nineteenth-century Boston / Millington W. Bergeson-Lockwood.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017045426 | ISBN 9781469640402 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469640419 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469640426 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : African AmericansMassachusettsBostonHistory19th century. | African AmericansPolitical activityMassachusettsBoston. | Partisanship. | Political partiesMassachusettsBostonHistory19th century. | Reconstruction (U.S. history, 18651877)MassachusettsBoston.

Classification: LCC F 73.9. N 4 B 47 2018 | DDC 323.1196/073074461dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045426

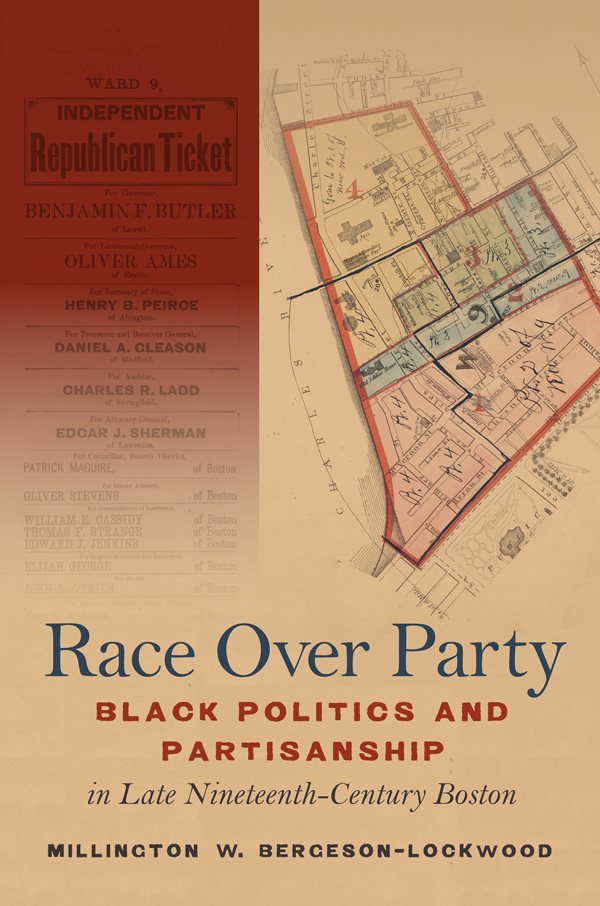

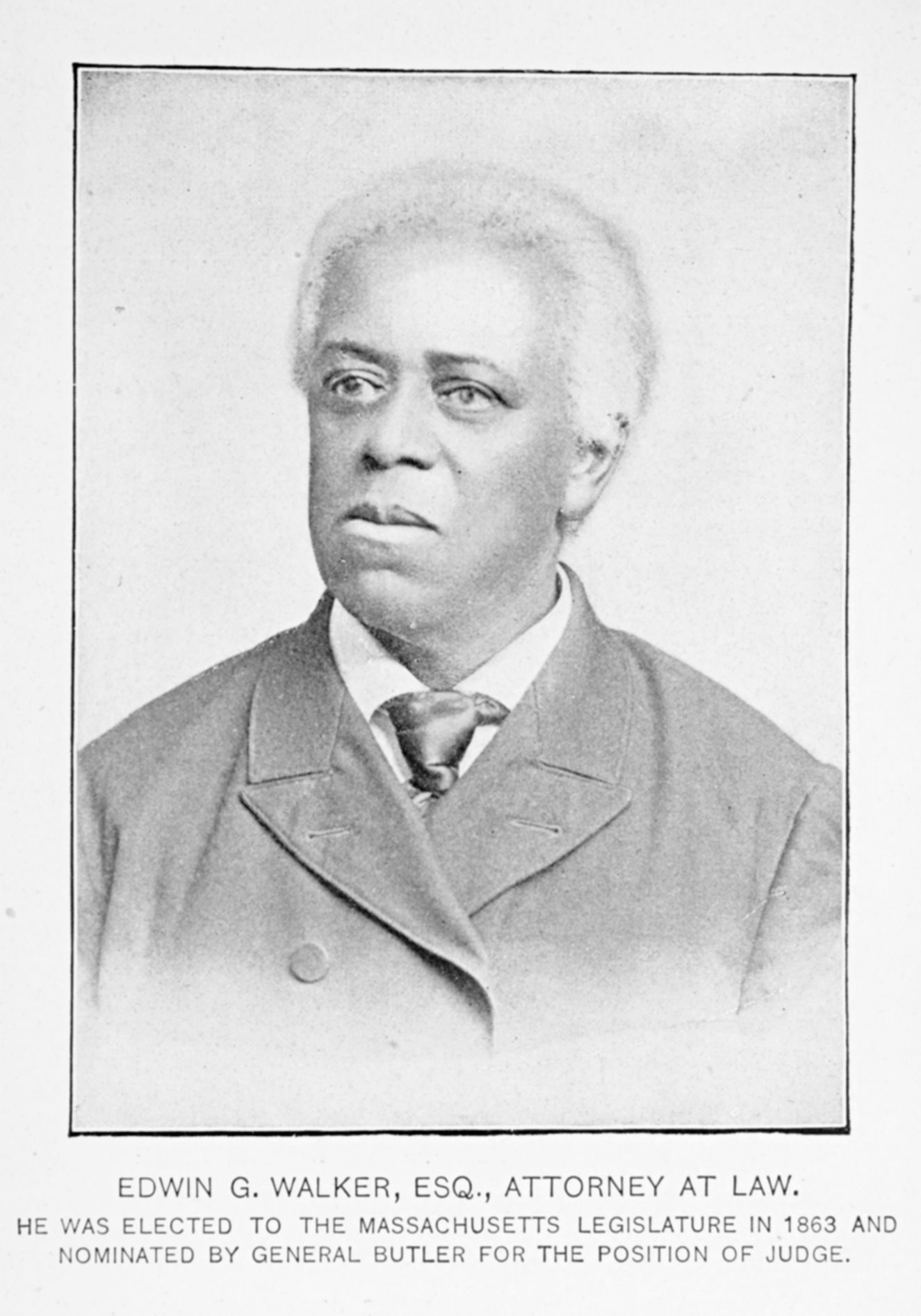

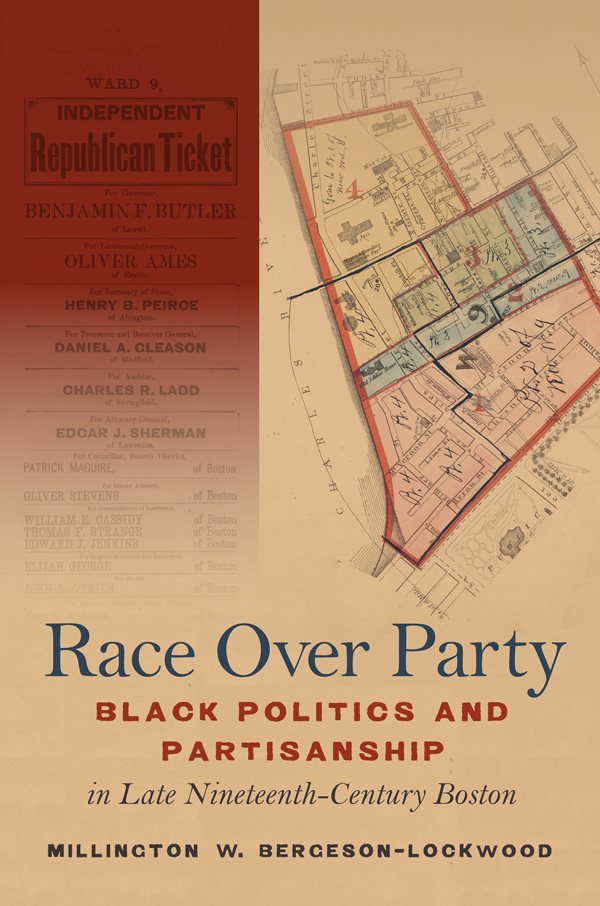

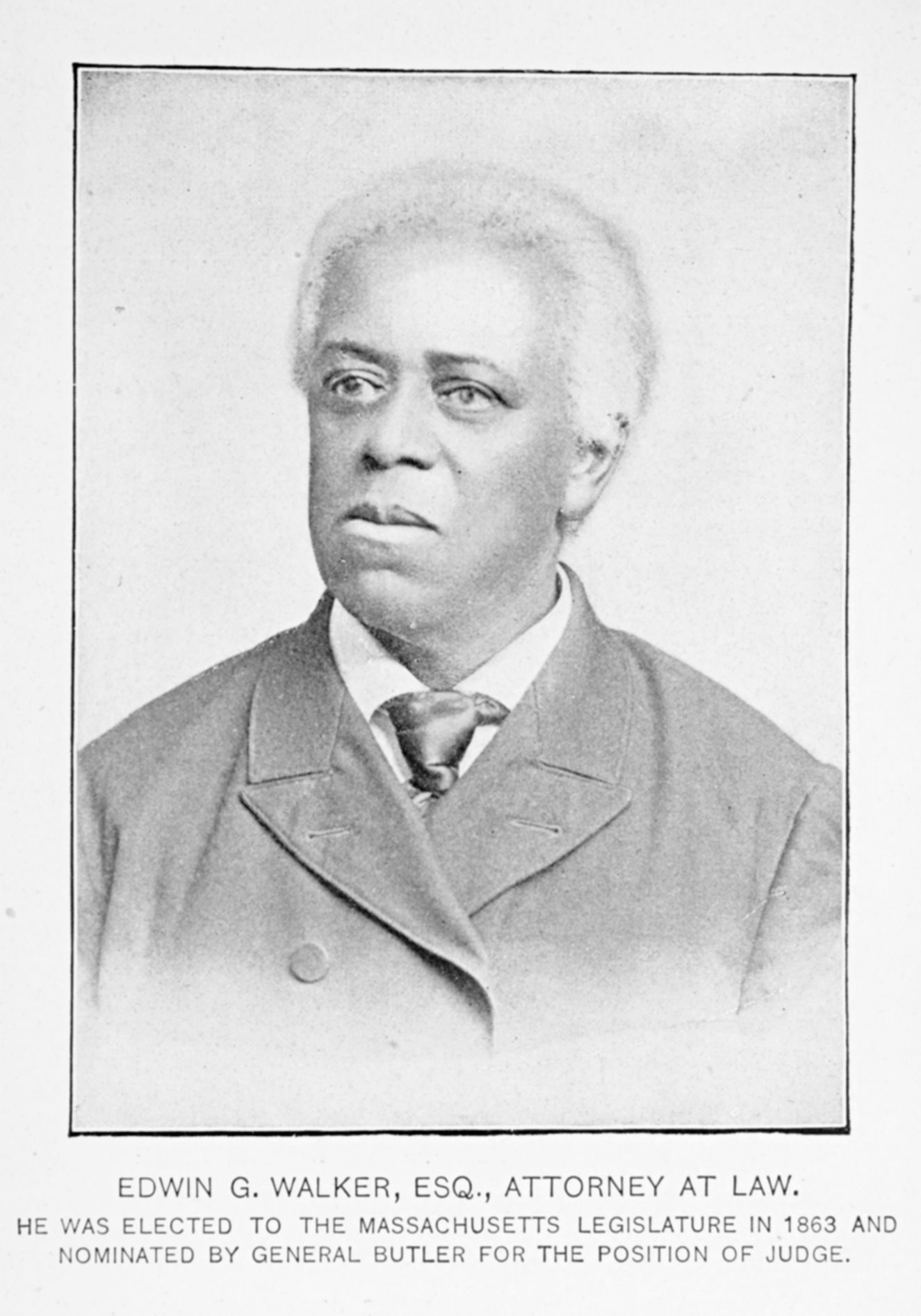

Jacket illustrations: front left, Boston Ward Nine ballot (used by permission of the Boston Athenum); front right, Boston Ward Nine voting precincts, 1878 (courtesy of the Boston City Archives); back, photograph of Edwin G. Walker from P. Thomas Stanford, Tragedy of the Negro in America (1897).

Portions of chapter four appeared previously in No Longer Pliant Tools: Urban Politics and Conflicts over African American Partisanship in 1880s Boston, Massachusetts, Journal of Urban History 44: 2 (March 2018): 169186.

To my father, Millington, for his love of the past

and

to Zora and Millington Samuel, my hope for the future

Contents

Illustrations

Race Over Party

Introduction

The Folly of Political Solidarity

On January 16, 1901, an interracial crowd of more than 1,500 men and women packed the Charles Street African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Bostons West End to capacity. They were there to mourn the loss of Edwin Garrison Walker, one of the citys most notable black activists. A black Civil War veterans association escorted his body in procession to the church, and some of Bostons other prominent black leaders were among his pallbearers. Walker was a fearless advocate for his race, one eulogy read, he was proud of the fact that he was a colored man and as such sought the highest ideals in life.

By the end of his life, Walker, like many other black activists, had grown increasingly bitter and disillusioned with not only the Republican Party, but with party politics generally. Black political independence had largely failed to transform American politics, and the conditions of African Americans nationally continued to deteriorate. With little to show for their decades of activism, and without the personal spoils of loyalty to a particular party, Walker and others looked to new organizations outside of party politics for the future of black political action.

The story of Walker and others who placed their faith in party politics and challenged the Republican Party is a tragedy. In the aftermath of the Civil War, they were believers in the power of partisan democracy to forge a greater future for African Americans. Some sought to transform the Republican establishment by staying loyal to the party of Lincoln. Others, like Walker, advocated independent politics as an alternative to what they recognized as the failure of the two major political parties, the Republican in particular, to improve and protect African American lives and rights in the aftermath of the Civil War. Even as independents criticized the current party structures, like loyal Republicans, they remained within the bounds of electoral partisan politics, hoping that one of the two parties would eventually emerge as the political vehicle for black progress. They worked tirelessly for decades, both inside and outside the official structures, to convince voters and party leadership of the importance of supporting black interests, from both a moral and politically pragmatic position, only to see white supremacy harden within American politics and the condition of black men and women worsen nationally. Their faith in partisan democracy had been tragically misplaced. The general failure of independent politics and black partisanship as a framework, however, is a tragedy with a silver lining, because it led black activists more firmly toward strategies of race-based organizing outside of the formal two-party political system.

Edwin Garrison Walker, P. Thomas Stanford, Tragedy of the Negro in America (Cambridge, MA, 1897). (Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.)

Although black activists were divided between remaining loyal Republicans or advocating independent politics, the eventual failure of partisan politics as a vehicle for racial justice was less a problem of black unity and organization than a betrayal by a white-dominated government and political structure refusing to make black rights and lives a priority and to uphold the values of American freedom. Black partisan activists and independents misplaced their faith in a party structure dominated by racism, that, as became evident by the beginning of the twentieth century, was never going to support black interests, no matter how unified the black electorate ever became. Campaigns for independent politics were part of early civil rights struggles Shawn Leigh Alexander describes as a bridge of ideas and activists, which inspired and provided a template for twentieth-century movements. Abandoned by supposed allies and disillusioned with party politics as an avenue for black uplift, activists formed new organizations and cultivated strategies to continue the black freedom struggle themselves. While continuing to advocate political independence in voting, these groups emphasized mass mobilization and direct activism as tools in the black freedom struggle, rather than holding out hope that political parties would ultimately serve their interests.

In this battle over black partisanship, Boston became a central venue. Urban politics became the battleground, and they organized to use electoral politics to challenge the status quo at both local and national levels. What happened in Boston is part of a national narrative of black politics, but is very much rooted in black Bostonians history of activism and the citys urban black political landscape. It is a story of community-level organizing to respond to both local and national politics, and the turn toward independent politics was as much a strategy to address local concerns as it was a response to national political changes. Independent political sentiment in Boston had a particular longevity as debates over black partisanship captivated community politics for at least four decades, with activists such as Edwin Walker active for the majority of the period.