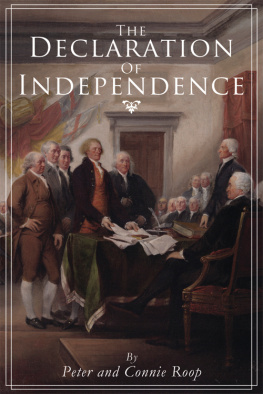

It began in 1492 when Christopher Columbus sailed west to find a new route to the Indies and stumbled onto an unknown continent. But if the origin of the colonial period was accidental, the ending was not. The representatives of the thirteen colonies who approved the Declaration of Independence in 1776 charted a collision course, aware of the obstacles in their path and the risks they were taking.

The events that led to their decision took place over a period of nearly 300 years. Looking back, the wonder is that it culminated so quickly. For a century after its discovery, the New World was little more than a lode to be mined by adventurers seeking profits. It wasnt until the end of the sixteenth century that serious efforts were made to establish permanent colonies. Even then, the perils of the journey and the threats of starvation and Indian attack inhibited settlement. Many colonists turned back when they discovered life in America wasnt what land developers promised.

But settlers gradually came, spurred, in part, by the fear of religious persecution, but above all, drawn by the hope of owning land. They were a mixed lot: English Separatists from Leiden, French Huguenots, Dutch burghers, Mennonite peasants from the Rhine Valley, and a few gentleman Anglicans. But they shared a quality of toughness.

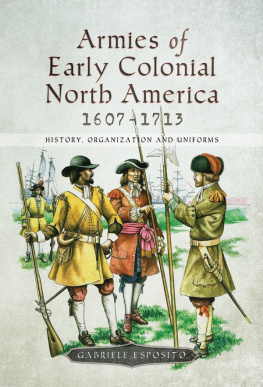

America was not a tranquil place to establish a home. Settlers found themselves immersed in continuous conflict as European nations maneuvered for power in the New World. Foreign policy made in London, Madrid, Paris, and The Hague turned America into a battleground for more than a century.

The English colonies were the underdogs in these frontier extensions of dynastic wars. Although English land claims stretched to the Pacific, the thirteen colonies occupied a narrow, vulnerable strip of land along the Atlantic seaboard. For the most part, colonists fended for themselves against the imperial troops of France and Spain. The Spanish were drawn to the New World in search of gold and silver, the French to the fur trade. The people who settled the English colonies understood these attractions, but most came determined to stay.

This tenacity enabled them to endure, but not to prevail. That required a sense of common purpose - and not surprisingly, it was a long time coming. The colonists differed enormously in nationality, religion, and language. They were a fragmented group more apt to pursue independence in diversity than in union. Eventually, a time came when colonists began to consider themselves not English or Dutch, not Virginians or New Yorkers, but Americans. As Americans, they were willing to sacrifice regional interests to serve common goals. As John Adams observed, there had been a change in the principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections of the people, and this was the real American Revolution .

When colonists came to grips with their destiny, it was because they had realized liberty and responsibility go together. No single event brought about that awareness. No single reason - the struggle for survival or the search for identity - can explain it. If we are to understand how the colonies became one nation and the colonists one people, we must examine their story from beginning to end.

When Christopher Columbus set out from Palos, Spain, on August 3, 1492, Western Europe had changed little since the age of Dante and Chaucer . An uneasy apathy, characteristic of the late Middle Ages , lay over most of the continent. The Catholic Church still exerted considerable authority, but its strength was uneven and its hold often tenuous as rebellious sovereigns defied popes or as corrupt popes forfeited the respect of the pious. Few states had rulers who sat securely on their thrones. Germany and Italy remained collections of independent or semi-independent cities and principalities. The emperors of the Holy Roman Empire hardly could be said to rule, but they controlled a nebulous portion of Central Europe. The emperor and pope were often at odds and sometimes at war as each contended for dominion over territories in northern Italy and neighboring regions. The continent was poised between two eras, the medieval world, with traditional patterns of thought, and the modern age, with changes that would affect every phase of life within a century.

One of the most powerful influences was the expansion of trade stimulated by demand for commodities from the East. The buying power of most of Europe had built slowly throughout the century as farming and sheep-raising improved, industries expanded, and the silver mines of Eastern Europe poured more bullion into the market. The increasing flow of money initiated an inflationary spiral bolstered by discoveries and conquests of the Spanish conquistadors in the New World that sent another stream of silver and gold to Europe. Money was becoming more plentiful, demand for goods in all the principal markets was strong, and prices were rising.

Trade had long been the lifeblood of many European communities. In the fifteenth century, however, demand for goods that had previously been restricted to the wealthy was increasing. More people could buy more goods, and merchants and ship owners struggled to meet demand.

The consequences of the Crusades went beyond the rescue of the holy places from the Muslims - or the Saracens , as they were called in those days. They exposed Europeans to Eastern cultures and made them aware of luxuries little known in their home countries. The Venetians , in particular, profited from the Crusades. They exacted high prices for warring knights to the East, and they loaded their returning galleys with expensive products collected from Alexandria, Cairo, and other Mediterranean ports. The Republic of Genoa , on the west coast of Italy, developed into a great seaport and a rival of the Queen of the Adriatic. Venice and Genoa established bases and imposed their rule at various points in the Mediterranean as they expanded trade between the Near East and distant European markets.

By the end of the fifteenth century, Venice and Genoa were in decline. The Ottoman Turks , who had supplanted the Seljuk Turks , the Arabs , and the Moors as the bearers of the banners of Islam, threatened their traditional trading routes. Previously, the leaders of Venice had reached an accommodation with the Seljuk Turks of Asia Minor and negotiated terms with the Mamelukes of Egypt. Genoa also had made favorable trade agreements in the Mediterranean before the rise of the Ottoman Turks. By the end of the century, however, the situation had changed. The Ottoman Turks, a warlike, organized military power, swept into Egypt and Asia Minor. They were diverted temporarily in 1402 by the attack on their rear from other Asiatic invaders under Tamerlane , but their power was short-lived, and the Ottoman Turks managed to take Constantinople in 1453. Moving into Europe, they marched to the walls of Vienna before they were stopped, and none knew when they might resume their advance.

The Turks developed sea power. Before this time, they had been an army of horsemen, but after they captured Constantinople, their naval prowess increased. Privateers flying the Turkish flag lurked in all principal seaports of North Africa. Many bases and colonies of Venice and Genoa surrendered to Turkish naval commanders. A crowning insult to the incumbent European powers occurred in 1480, when Muhammad II captured the Italian town of Otranto and set up a market for the sale of Christian slaves. By 1565, the Turks attacked Malta and nearly captured it. The days when the Venetians ruled the Mediterranean and Venetian merchants held a monopoly of the trade in Eastern luxuries ended before Columbus set sail.