For Duncan, Jacob, and Sophia,

you share this particular heritage with me,

so I dedicate this story to you and your families.

CONTENTS

THIS IS THE STORY of how Australia became home. The heroes and heroines of this story are everyday folk who helped people a continent and generate a nation. They are my kin, and I share their stories because their joys and struggles echo millions of others that have been forgotten. This is a history of the land my people settled on, lived in, and knew. Spanning a period from the late eighteenth century into the time of living memory, the documentary trail of my familys experience in Australia reveals a real peoples history of our nation.

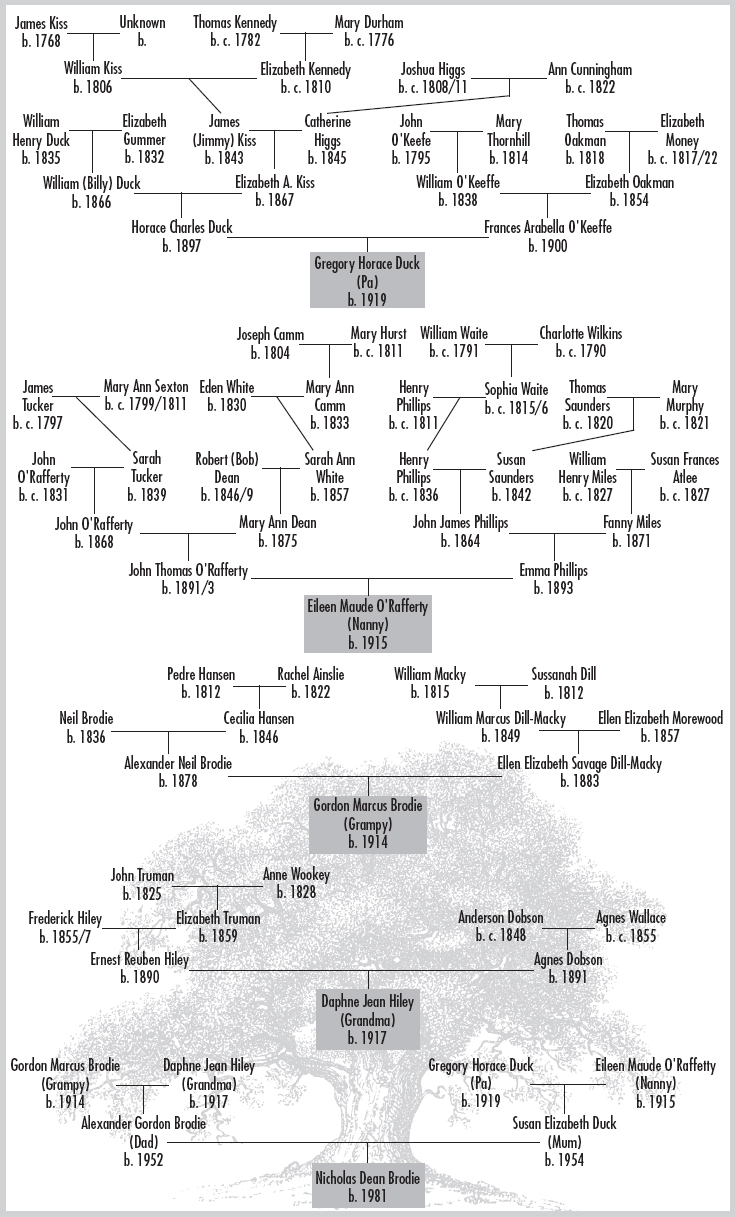

My connection with this continent and its people stretches back before my birth in Wagga Wagga, or Wagga, as it is often referred to, beside the Murrumbidgee River, over the plains and into the mountains, through the valleys, to the beaches, and beyond the seas. My fathers fathers grandfather was the first Brodie in my line to arrive in Australia, making landfall in the 1860s. But this is not only the story of the Brodies. Rather, I have pursued every branch, twig, and leaf on my family tree to discover how Australia became home to a diversity of people.

My mothers fathers maternal grandmothers people took me back to a penal colony struggling on the edge of empire in the eighteenth century. Many more of my people arrived through the nineteenth century to make this place their home. Their children were born here. Some of my kin saw Australia federate, some fought under its banners. This is a continent that my people helped populate with coachmen, farmers, stockmen, squatters, selectors, nurses, butchers, bakers, waitresses, unknown mothers, and unmarked graves. From Botany Bay to Federation to Gallipoli to Darwin, this is more than the narrative we know of those times. It is the sum of my ancestors experiences.

Like many of us, I began to wonder about my ancestral past, and set out to recover a sense of what had been lost. But through this journey I also aimed to reclaim my place in Australias history, to put my people back into the national story. The telling and understanding of Australias past, in part or whole, has too often been allowed to become both an obscure academic plaything and an argument machine for facile political commentary. There are ideologies of Australian history, both right and left, whose proponents historicise the past to suit their own professional or polemical agendas. Some deny the tragedies of our past, others judge it. Some misunderstand, others misconstrue. Few really learn from it. Australian history has been rendered too political, bizarrely isolated from the rest of the world, overly subjective, and, frankly, often boring. But most of the real stories within our continent are none of these things. We have fascinating and important tales to tell. There have been some excellent exceptions to this trend, but they have generally focused on individual events or issues, and as yet they have not been pulled together. We have not had an honest history of the entire national story for a generation. To restore a true democratic history of this continent and nation requires a new focus on the demos, the people. And so I chose my people, my kin.

My people mainly originated from the British Isles. They were mostly ordinary folk, but their journeys encompass an extraordinary story. Fortunately their interactions with Australias Indigenous peoples and other settler minorities allow some of the experiences of these groups to unfold through this story as naturally occurring realities, not forced scholarly or politicised impositions. And the same is true of wider political and imperial narratives. My peoples stories, documented from the 1790s to the present, reflect the historical record of the period from British colonisation onwards. Major events and historical trends influence them, and are influenced by them, each situation allowing me to see historical agent and historical context interacting through time.

Having begun to discern their tracks, I followed my kin across this land, and allowed Australias past to reveal itself through them, on its own terms. This is therefore a national history whose structure is entirely the product of original research. It is unburdened by a slavish need to repeat our tired mythologised narratives of memorable events, so some of our cosy stories will be challenged. And this book will not doff its proverbial cap to educational preoccupations and so become another short history or concise volume; it is bigger than that. This charting of my particular crimson thread serves to guide us through that wider set of bonds, the broader kinship network, which make us all a people. It therefore bridges the gaps between memorable events, and can integrate the fruits of scholarly research, without being reduced to a recitation of those events or a summary of scholarship.

What follows is a history of Australia told through overlapping ancestral tales. By the accident of family connection to this historian, me, people otherwise poorly documented have become central to the nations social history. The past has therefore been populated without some of those prominent biases that strangled a generation of historical discourse. I strive to wear no black armband or white blindfold, or any other metaphorical party clothes. You cannot choose your family, and nor did I. They are here, warts and all: convicts, soldiers, sailors, good wives, bad husbands, the young, the elderly, the famous, the obscure, and many of their animals. I am seeking by this to achieve those simplest of historical objectives: to answer the eternal questions of what happened, why, where, when, how, to whom, and with what effect?

Historians are normally cursed to inhabit worlds in which they do not rightly belong. Spectral observers, they are bound by the real tyrant of distance: time. They can gaze so heavily upon a moment as to take on its attributes, forever lost between the past and the present. Or they can utterly fail, through being bounded to their everyday world, to see another time or place as the different thing it is. But they can never be in that moment they study. Unless, that is, perhaps some small forgotten part of them was there. Could this then become not history, but remembering?

Tales told, documents written, photographs taken, and objects handled all mark the many journeys that carried thousands of people to these shores and across this land. But we are all challenged by the vagaries of memories and evidence. As people disperse, so can memory. As the ground claims our forebears, so too does it claim their footprints. Whether they lived 45,000 years ago or yesterday, our capacity to recall our ancestors comes from recognising those toe marks in the ancient sand, or reading their faded words scratched on parchment and paper.

I have tracked my people through the records of their times in ships and in prisons, their moments of fame in local newspapers, their hardships, their headstones, oral traditions passed down, court transcripts, their letters and photographs, and the many records of their births, deaths, and marriages. I have followed them over the seas to the lands of their birth, and back again as they sailed on creaking and reeking ships to their new homeland, their childrens and my birth land. In doing so, I push our understandings of being Australian beyond the academic confines of race, class, and gender, the binaries of invasion or settlement, the politics of left or right, and the great discontinuities of historical treatment between over there and over here, back then and here now. Following my kin is not about degenerating into ancestor worship, jingoistic nationalism, or its guilt-ridden antitheses. Rather, it is about overcoming the need to read ideology into the past, and instead to listen to it on its own terms.