Contents

Giant

Scots wha hae wi Wallace bled,

Scots wham Bruce has oft-times led,

Welcome tae yer gory bed.

Or tae victory.

Robert Burns, Scots wha hae, 1793

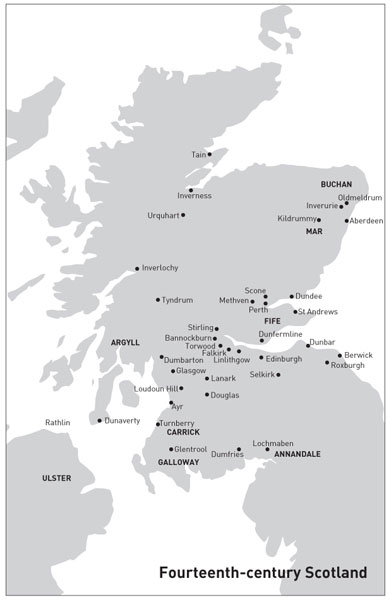

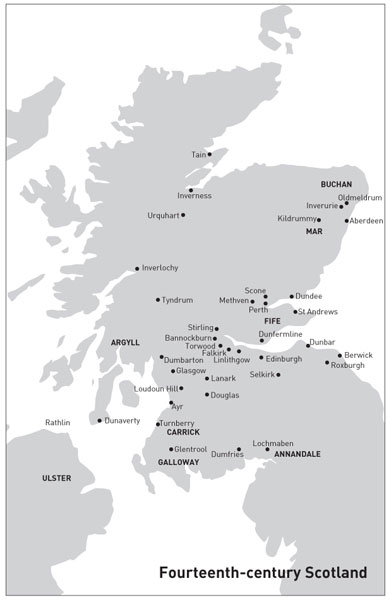

Perched on a rocky summit high above a plain dotted with vineyards, the Castle of the Stars at Teba in Andaluca salutes the vastness of the azure sky. This is a dry land, drawn from a palate of browns and yellows and ochres. It is very different from Scotland, that wet, green place 1,800 miles away. And yet, on a late summers day nearly 700 years ago, Scotland and Spain joined together on this very spot.

The memory of that moment lives on in Tebas small, neat square beneath the castle, where a giant slab of granite commemorates the help given by the Good Sir James Douglas, formidable general and close friend of King Robert the Bruce, to Alfonso XI of Castile against the Moors, who still occupied much of Spain. Douglas had been entrusted with the task of taking his kings heart on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, a journey Bruce had always wanted to make in life but had never managed. Alas, Douglas and the Scots with him, in typically gung-ho fashion, charged so deep into enemy lines that they were cut off and most of them killed in the ensuing battle on 25 August 1330, though the castle was captured soon after. Both the body of Sir James and the casket containing Bruces heart were brought home to Scotland. And so, after this final arduous journey, King Robert, who had died over a year earlier, was allowed to rest in peace, a legend both at home and abroad.

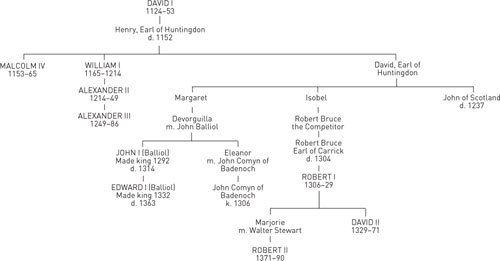

It was not always thus. Robert the Bruce was not born to be a giant. It is true that he inherited wealth, land and considerable privilege, but until the age of 32, his name is not one that should have drifted beyond the peaceful sanctuary of Scotlands more obscure history books, scarcely troubling the consciousness of present-day Scots, never mind inhabitants of the wider world. Bruce lived through extraordinary times, however, and these proved the perfect testing ground for his genius, forging a military leader with an international reputation for triumphing against the odds and putting his small, peripheral kingdom on the European map.

Much of what he did should make for uncomfortable reading. He was overwhelmingly ambitious, and ruthless with it a fourteenth-century Macbeth in the eyes of some: a murderer, usurper and excommunicate. But he was also an extraordinarily innovative military commander who succeeded in liberating the medieval kingdom of Scotland from the control of its powerful southern neighbour, England. And he did so, to begin with at least, with the most limited of resources.

In 1314, at the Battle of Bannockburn, he defeated a numerically and as contemporaries saw it tactically superior cavalry army with a force made up almost entirely of foot soldiers armed with spears. His reign, partly as a result of the particular circumstances in which he took the throne, produced one of the most passionate and early expressions of the right of a nation to self-determination in medieval Europe. (Ironically, perhaps, the experience of fighting against Scotland also helped to crystallise and define Englands identity and prompted her kings to remodel their armies, focusing also on the capability of the foot soldier especially one armed with the longbow which then served them so well during the Hundred Years War with France.) If Robert Bruce is less well known than other great military leaders, it is not because his deeds and reputation are less worthy, but because the theatre of war that he dominated has been undeservedly overlooked.

Today, Robert Bruce is regularly awarded the sobriquet of hero king in Scotland. In 2006 he came third, with 12 per cent of the vote, in a list of most important Scots, behind William Wallace and Robert Burns. even by his enemies, a moniker that hints at affection among his own supporters and profound respect well beyond. The Bruce was also the title given to the great epic poem written forty years after his death by Archdeacon John Barbour. Today he is most commonly referred to as Robert the Bruce.

However, a degree of ambivalence towards his reputation has developed over the last few centuries. Pursuit of his ambition to claim the throne of an independent Scotland is contrasted with the supposedly selfless and ideologically driven patriotism of William Wallace, another key figure in the Scottish wars with England. A strange form of class war has been projected on to these two heroes, with Wallace emerging as the champion of the working man, from whose forefathers he is deemed to spring, whilst Bruce is viewed as a member of a shifty, self-seeking nobility who espoused patriotism only when it was expedient to do so.

This version of their characters attained its most potent and wide-reaching form in the 1995 film Braveheart. Then the cult of Wallace, which had existed in Scotland for at least 500 years, reached a global audience. The film united two themes that struck a chord from Motherwell to Memphis to Medina: the desire to live freely and the ability of one man to change the world. Freedom, as it would have been understood in the thirteenth century, was a vastly different concept than it is today, rooted as it was in the social status of male property owners rather than the right of one nation or ethnic group to be responsible for its own destiny without interference from another. Equally, the myth of Wallace as a superman has long resided in his apparent responsibility for almost every blow struck in Scotlands struggle to rid herself of English rule during his lifetime, up to and including (in the film) fathering the next King of England after a brief liaison with the Princess of Wales. In reality, Wallace was one of a number of Scottish military commanders and, though he did become Guardian of Scotland from the autumn of 1297 until his defeat at the Battle of Falkirk in July 1298, he later played a subsidiary role in the army of a subsequent Guardian. Even at his famous victory at Stirling Bridge in September 1297, he shared command with a young nobleman from northern Scotland, Andrew Murray.

Not even Hollywood dared to change Wallaces grisly demise, but at least the doomed hero could be portrayed showing Robert the Bruce the way, giving the film a happy ending at Bannockburn, which, so it was implied, brought Scotland her freedom. This is certainly not a novel interpretation; almost from the beginning, histories of the wars written from a Scottish perspective have stressed what Bruce inherited from Wallace. But in reality, and despite the undeniably challenging fact that Bruces ambitions brought him to fight his own people as much as the English, there is no comparison between the two men in terms of innovation, leadership and success. Wallace is the short-lived, ill-fated martyr. Bruce is the enduring, successful military genius the monarch who, against the odds and the fallout of his own actions, forcibly united his kingdom and reigned for over two decades. A giant.

But Anthony Bek, bishop of Durham, put this question to him [Edward I]:

If Robert of Bruce were king of Scotland, where would Edward, king of England, be? For this Robert is of the noblest stock of all England, and, with him, the kingdom of Scotland is very strong in itself; and, in times gone by, a great deal of mischief has been wrought to the kings of England by those of Scotland.

John of Fordun,

Chronicle of the Scottish Nation , 1873

Next page