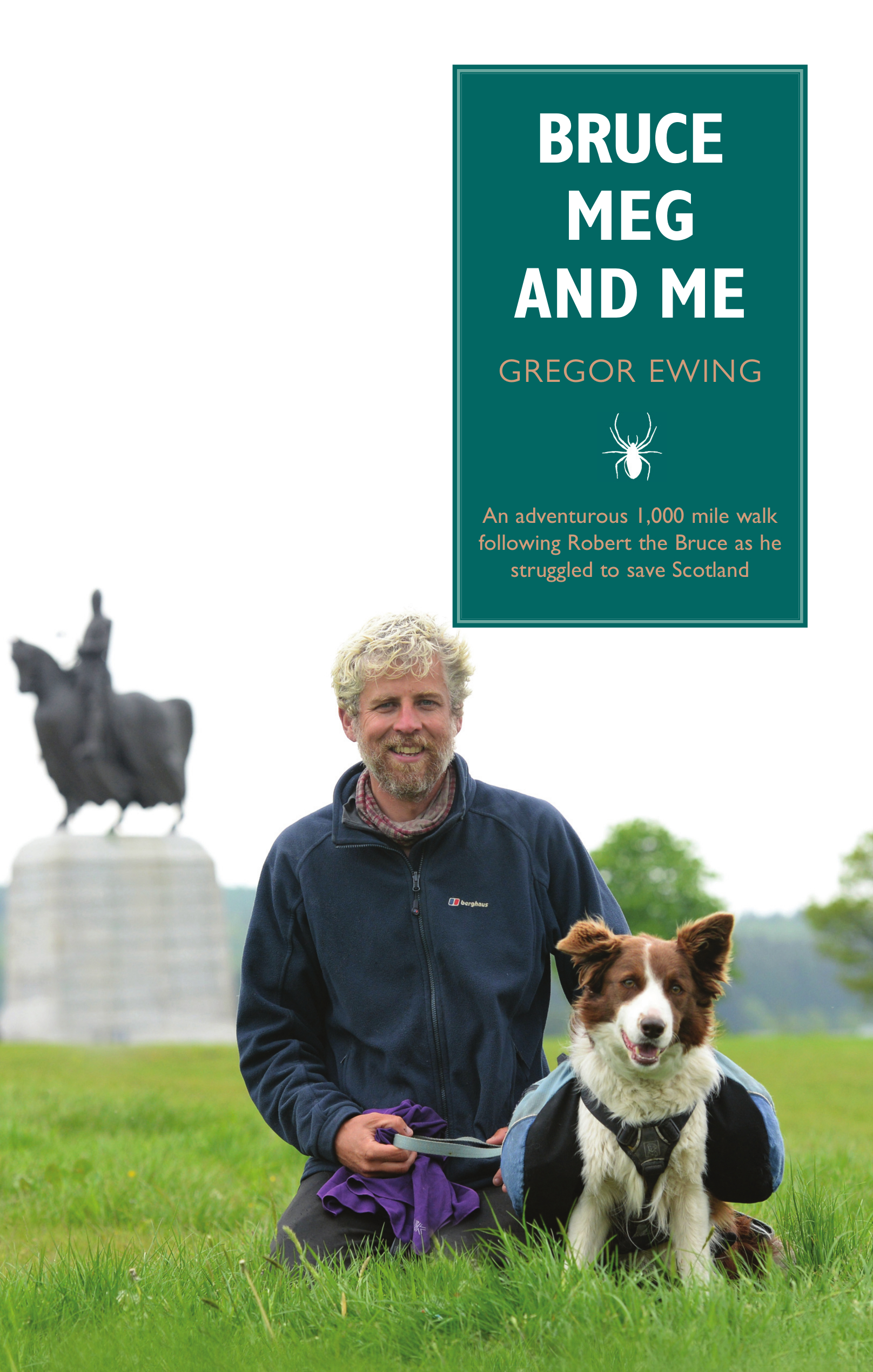

GREGOR EWING has a passion for the outdoors that is only matched by his interest in history. His first book, Charlie, Meg and Me , recounts his Mile walk in 2012 accompanied by border collie, Meg following the route of Bonnie Prince Charlies flight after the Battle of Culloden. In 2014 , he walked over 1,000 miles in a continuous journey following in the footsteps of Robert the Bruce. Bruce, Meg and Me is the story of the expedition. Gregor has given talks at literary, history and outdoor festivals throughout Scotland and has spoken at events organised by the National Library of Scotland and Culloden Battlefield Centre. He lives in Falkirk with his wife, Nicola, and three daughters, Sophie, Kara and Abbie. The dogs, Meg and Ailsa, complete the female entourage in his household.

Bruce, Meg and Me

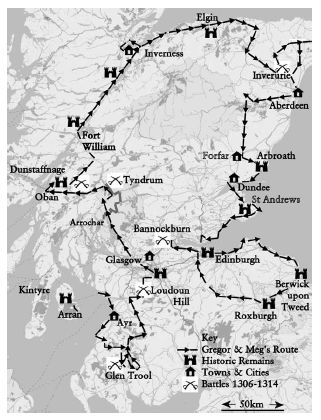

An adventurous 1,000 mile walk following Robert the Bruce as he struggled to save Scotland

GREGOR EWING

Luath Press Limited

Edinburgh

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2015

ISBN: (EBK) 978-1-910324-60-8

(BK) 978-1-910021-80-4

The authors right to be identified as author of this book

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

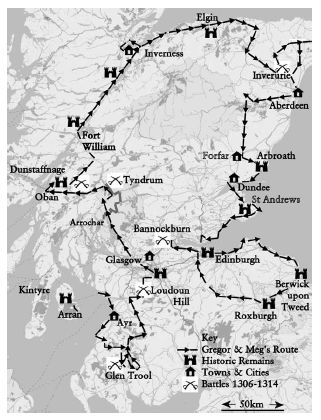

Maps Gregor Ewing. Base map information supplied

by Open Street & Cycle maps (and) contributors

( www.openstreetmap.org ) and reproduced under the

Creative Commons Licence.

Gregor Ewing 2015

Contents

List of Maps

The Complete Journey

To Nicola, Sophie, Kara and Abbie

Acknowledgements

It was only through the support of my wife Nicola that I was able to undertake my journey. A loving thanks to her for keeping the home fires burning.

Friends who met or accompanied on the way gave me great encouragement and helped keep me sane. Especially, George, Jennifer, Graeme and Iain.

Thanks to Andy Smith, Ian Scott and Jennie Renton at Luath who all helped turn my manuscript into the book in front of you today.

Once again I am grateful to Dr Tony Pollard, for finding time in his busy schedule to write a thoughtful and amusing foreword.

Foreword

SAY THE NAME Robert the Bruce and the next word that comes to mind is very likely Bannockburn. And even now, after years of studying the Scottish Wars of Independence and visiting their many battlefields it is still Bannockburn that I most strongly associate with him, despite the fact that his life story, and his military experience, consisted of so much more. I can perhaps be forgiven for this single-mindedness though, as the Battle of Bannockburn has probably taken up more of my time as a battlefield archaeologist than any other, from my first failure to find evidence for the battle site while making the television series Two Men in a Trench back in 2003 , to finally being able to say with confidence where it was fought after an ambitious project in 201314 .

It was the 700 Th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn in 2014 that really brought Robert the Bruce alive for many people and it was certainly the motivation for that successful project and the associated BBC TV programmes, The Quest for Bannockburn, presented by my old friend Neil Oliver and myself. One of the great pleasures of that project was the involvement of locals and school children in the quest; it was a real community undertaking, in which well over 1 , 000 volunteers took part. There were also other events to mark the occasion, which just happened to coincide closely with the Referendum for Scottish Independence (which failed to emulate Bruces achievements), such as the opening of the new state-of-the-art visitor centre and the re-enactment of the battle at the Bannockburn Live weekend organised by the National Trust for Scotland.

But away from the crowds and the TV screens, a more personal and far more demanding tribute to the great man was taking place. Over the best part of two months in early 2014 , Gregor Ewing and his faithful dog, Meg, undertook an epic walk of 1 , 000 miles as they followed the route of Robert the Bruces movements through Scotland prior to the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1314 . This was not the first time they had hiked back into history, in 2012 the pair followed the trail of Bonnie Prince Charlie from his defeat at Culloden in April 1746 to his rescue by a French ship off the west coast of Scotland the following August (a mere 530 -mile stroll).

The idea of discovering and communicating history through the medium of a journey has always appealed to me. As a schoolboy, I hatched a scheme to follow the 1 , 170 mile route taken by the Nez Perc Indians under Chief Joseph from their reservation to freedom in Canada in 1877 , all the way pursued by the US Army. Despite putting up some impressive fights they didnt make it. My plan, which I spent many an hour pondering, was to follow the route on the back of one of the Appaloosa ponies for which the tribe were well known. But alas, a daydream it remained. Whats so impressive about Gregor is that he turns his daydreams into reality.

Back in 2014 , while I roamed the carse fields adjacent to the banks of the Bannockburn, monitoring the progress of metal-detecting teams or keeping an eye on our volunteer archaeologists, so Gregor and Meg progressed from one corner of the country to the next, moving from one Bruce milestone to another. But as he documents here, at one point prior to setting out on his expedition he found time to take part in that project, digging one of our many test pits and to his delight finding a sherd of medieval pottery in it.

The journey has long been a metaphor for the human experience, albeit one that has recently strayed into saccharin clich when it comes to the sort of challenges pursued on TV talent shows and dance competitions. In this book, however, Gregor reminds us that some of the most important periods of our history are made up of journeys, with momentous events such as powerful marriages, coronations and battles punctuating voyages, marches and expeditions, which in the days before motorised transport required considerable amounts of determination and stamina, and as Gregor found out, a hefty chunk of time.

Bruce was determined to be king of Scotland, to be the winner of what became known as the Great Cause, even if it meant committing murder, seeing his family almost wiped out, waging war and laying waste to large tracts of his own country. Travelling around the kingdom was an essential part of that process. In the days before mass communication it was essential that a monarch was seen by his people (seeing is after all believing), and Bruce was a graduate of the if you want something done well, do it yourself school. It is said that even the appearance of an unwell Bruce, who at that point was carried on a litter, was enough to send his enemies fleeing the field at Inverurie in 1308 . In any case, his army was never really big enough to send men off on one campaign while he fought another an exception was the Irish campaign of 131518 and that ended in disaster (see below). So it was that he spent much of his life marching from one place to another, exterminating his enemies, impressing his allies and awing his people.

Winning the crown was hard work, and even though victory at Bannockburn was to establish him as king in Scotland, there was a long way to go before England would accept the independence of their northern neighbour (the Scottish Wars of Independence did not come to an end until 1355 ). Its a fact that even now, after the 700 Th anniversary, many people dont realise that Bannockburn did not end the story, but as Gregors book so ably demonstrates, there was also lot going in Bruces life before the most famous battle in Scotlands history was fought.