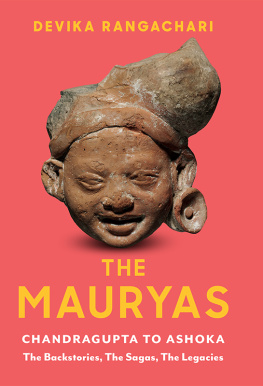

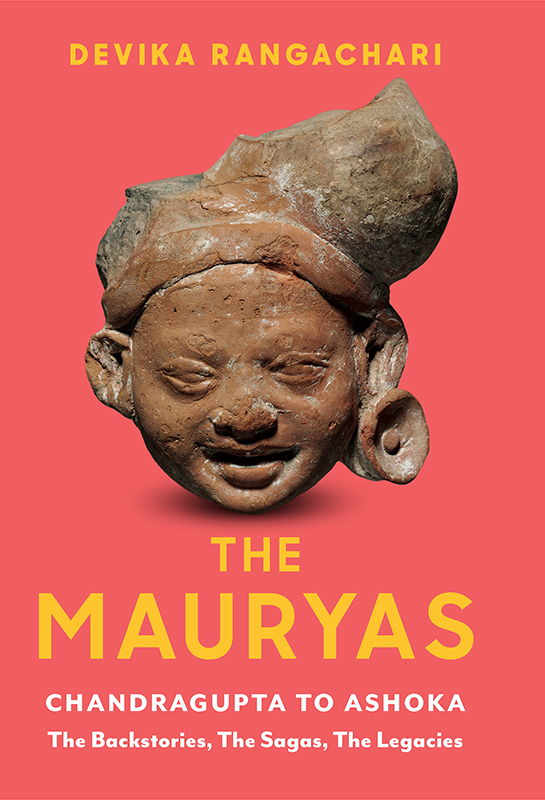

THE

MAURYAS

THE

MAURYAS

CHANDRAGUPTA TO ASHOKA

The Backstories, The Sagas, The Legacies

DEVIKA RANGACHARI

To Ammamy strength, my solace, my soul

INTRODUCTION

H istory encompasses our past, the entirety of our lived experience and our shared inheritance. It is also a most generous discipline: everyone has access to it and can claim it as their own, and it contains within it several other fields of study that endlessly diverge and converge to reconstruct it. It can be, at once, extremely comforting and totally intimidating; unbelievably vast and highly specific. As a practitioner in this field and one who has loved it ever since she read her first work of historical fiction as a child, I feel equipped and impelled to make certain general observations about itto lay out the ground, as it werebefore I tackle the Mauryas.

Let us begin with a truism: history is selective. The history that a non-historian reads is based on the selection of facts by a historian who then, despite their best efforts, will interpose themselves between you and the fact. So if you grow up swearing belief in a particular view of history, it is because you have decided, at some point, that the historian you have read is truthful and objective, and that their facts are sacrosanct. This, as anyone who is trained in the rigours of the discipline knows, is often very far from the truth.

So how does the non-historian arrive at an objective view of the past? Put very simply, if one gathers information from various secondary sources, it is possible to garner a more or less accurate picture despite the large gaps that will inevitably exist in our knowledge given the lack of sources for some periods in history. However, it definitely does not mean that anyone and everyone can master the subject from merely ploughing through a pile of books. History is a very specialised discipline, as noted above, and you should, ideally, undergo the rigorous training and research regimen that goes with the field before you appropriate the right to make statements about it. Making sweeping assertions about the past simply because you like history and you think you know about it is as unfair and unjustifiable as pontificating on Physics simply because you are interested in the universe and its workings. It also does not mean, for instance, that anyone with a mastery over myth can proceed to label themselves as a historian. Myth is, emphatically, not history and there is nothing irreverent or injurious about reiterating this simple fact. Myths might reflect some aspects of the past, particularly of the times in which they were composed, but to see them as a straightforward rendition of historical fact is ridiculous and completely unwarranted.

It is also unfair to expect someone with a background in historical studies to know everything about the past. To say that the canvas of history is vast is akin to noting that the sky is large. History is, basically, everything that happened from the beginning of time to the present, so you cannot actually ask a specialist in medieval history, for instance, to tell you all about the Indus Valley civilisation. She will, undoubtedly, know the basics but, in all probability, not much more than that. Academics across the board are required to micro-specialise in areas of their interest and historians are no exception. Whether that is a sensible factor or not is a different discussion altogether.

Everyone is familiar with the contention that history favours the victor and suppresses facts about the vanquished and the oppressed. This is true but is, actually, the tip of the iceberg. The point is that a historical narrative cannot possibly contain the names of each and every person who has ever appeared on the historical stage. Consider the massive geographical breadth of this country, coupled with the thousands of regions within it with their own specific political and social trajectories. To include everyone who wielded any political and/ or social influence at all in our historical narratives would be a logistical nightmare. Textbooks would, in that case, be voluminous and near-impossible to negotiate, and general histories would be largely unreadable.

Historians who author textbooks or general narratives are, therefore, forced to make a somewhat judicious selection of some important people who left a considerable mark on historyby dint of effecting political changes, or leaving behind information on themselves in different sources, or having caught the popular imagination for a range of reasonsand omit a whole lot of others. By some tacitand often insidiousconsensus, certain names alone are mentioned repeatedly in historical delineations of the Indian past, thereby creating the impression that they were the only ones whose existence mattered.

The casualties of this approach are those who fall into the cracks of history and remain there in oblivion unless they have the fortune of being resurrected by some historian or the other to suit particular research agendas. For every individual who is known, there are several moreequally remarkable and noteworthy and fascinatingwaiting on the sidelines for some sort of popular acknowledgement. Yet, we often lack the ability to look beyond the obvious into the enchanting shadows of the past. Ironically, though, the sources testify to their existence and provide tantalising glimpses of their personalities and contributions but they are deemed to be insignificant in the scheme of things, persons who would mar the neat outline of the ubiquitous historical narrative. Thus, they are consigned to what has been poetically referred to as the dustbin of history.

Let us, for instance, talk about what history as we know it today is mostly about. It is, in fact, his-story and has very little to do with the women of the past. So the overwhelming impression conveyedthrough textbooks and a majority of secondary sourcesis that it was the men who went out and fought battles, founded kingdoms, made the laws, built magnificent structures and so on. There is usually a token passage on the status of women in differing historical periods that, more often than not, focuses on the jewellery and clothes that they wore, which implies that all through history, women were obsessing daily about how they looked while the men did the real things. This flies in the face of the evidence that a wide range of historical sources convey about women in the past.

The truth is that women were hugely important in the political, social, economic and religious spheres in every historical period, some of themin certain phases of the pastruling on or behind the throne, mediating in court politics, building structures to perpetuate their names and donating to different causesand this applies to both the royal and non-royal sections of society. Yet, most historians ignore what the sources say, in this regard, and choose to tell you a different tale altogether. The familiar spectre of the historian and their agenda between you and the source again! Thus, there is an unfortunate but concerted effort to invisibilise women and their contributions in historical narratives, leading to a male-centricand, therefore, skewedversion of the past across age groups.

Notable exceptions to this trend are a handful of namesRazia Sultan, Rani Lakshmibai, Jahanara and Mother Teresaand these are the ones that schoolchildren across the country obediently trot out when asked to identify some women in Indian history that they remember reading about. When, however, you ask them to name any woman before the thirteenth century, the date pertaining to Razia (the earliest woman usually mentioned), they draw a collective blank. If you extend this line of enquiry and go further back in time, some of them instinctively say no when asked whether women existed during the Indus Valley civilisation, for instance, and then proceed to look sheepish when the ludicrousness of their answer dawns upon them.

Next page