ASHOKA

in Ancient India

ASHOKA

in Ancient India

NAYANJOT LAHIRI

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2015

Copyright Nayanjot Lahiri, 2015

All rights reserved

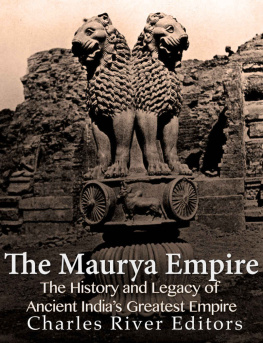

Jacket photograph: Lion Capital from the Pillar of Ashoka, Indian School (3rd century BCE) Sarnath Museum, Uttar Pradesh, India/Bridgeman Images

Jacket design: Annamarie McMahon Why

First published in India by Permanent Black, 2015

First Harvard University Press edition, 2015

ISBN 978-0-674-91525-1 (EPUB)

The Library of Congress has catalogued the print edition of this book as follows:

Lahiri, Nayanjot.

Ashoka in ancient India / Nayanjot Lahiri.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Asoka, King of Magadha, active 259 B.C. 2. IndiaKings and rulersBiography. 3. IndiaHistoryMaurya dynasty, ca. 322 B.C.ca. 185 B.C. I. Title.

DS451.5.L35 2015

934'.045092dc23

[B]

for

RUKUN

As works of the imagination, the historians work and the novelists work do not differ.

Where they do differ is that the historians picture is meant to be true.

R.G. Collingwood, The Historical Imagination (1935)

Contents

Items in italics denote colour pictures

PRELUDE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

EPILOGUE

THIS BOOK ORIGINATED IN THE STRANGEST OF CIRCUMSTANCES. An email arrived from Sharmila Sen of Harvard University Press, inviting me to consider doing a single-volume biography of Ashoka which, as she put it, should be geared for a general, educated audience without sacrificing scholarship. This was in the summer of 2009, during a phase in my life when I was steeped in administrative work at the University of Delhi. I had never met Sharmila, nor corresponded with her, and she is probably not even aware that her invitation became a lifeline of sorts, pulling me out of the fatigue of executive duties and endless files. While it took a couple of years before I could immerse myself in the fieldwork around the landscapes where this book took shape, I owe a great deal to Sharmila for writing to me and taking her chances. Over the years our conversations, and the unending supply of books on antiquity sent by her, have proved invaluable.

A number of friends and colleagues have supported this work in various ways. While he was vice chancellor of the University of Delhi, Deepak Pental gave me a powerful official position in his administration which provided a ringside view of how authority is exercised. That experiencenotwithstanding the fact that Professor Pental had an entirely different end in mindhas played an important role in shaping my understanding of political authority in ancient India. Ramachandra Guha sent comments and insights on the initial proposal and has supported it ever since with great enthusiasm. Ratna Ramans companionship and formidable knowledge of all things culinary made fieldwork enormously pleasant in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Uttar Pradesh. I am also grateful to Devika Rangachari, Dilip Chakrabarti, Jairam Ramesh, Rakesh Tiwari, Vivek Suneja, and Upinder Singh for reading and critiquing parts of the manuscript. Ella Dattas advice on acquiring images was tremendously helpful. Kesavan Veluthat and Shalini Shah in Delhi and Parimal Rupani in Junagadh provided some important references, and Suryanarayana Nanda guided me through the inscriptions of Ashoka. I must also acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers who read the manuscript for Permanent Black and Harvard University Press with great care and insight. Some of their suggestions have improved the narrative in many ways.

At the various places where I pursued this research, I owe a profound debt to many institutions and people, especially the officers of the Archaeological Survey of India: in Junagadh, Rasik Bhatt, J.P. Bhatt, M. Sutaria, and K.C. Nauriyal; in Nepal, Hari D. Rai; in Karnataka and Andhra, S.V.P. Hallakati and Srinivas; in Uttar Pradesh, Subhash Yadav; in Madhya Pradesh, S.B. Ota; in Delhi, V.N. Prabhakar, the staff of the Archaeological Survey of India library, especially Satpal Singh, and Dr Narendra Kumar at the Central Library of the University of Delhi.

Because of the disappearance of high editorial skills in book publishing nowadays, Rukun Advani is already the subject of folklore among the discerning. The reason, in my experience, has to do with his breadth of knowledge and the surgical skill with which he transforms scripts when he relates well to them and their authors. His imagination and precision have made doing books with him the most intensely enjoyable experience of my professional life, and this book has been no different. His interest in the sound and music of prose as part of the art of writing well has also sustained me in numerous ways. For adding lightness to the often ponderous pen of a professional archaeologist, and much else, this book is dedicated to him.

At a purely personal level my greatest debt is to Kishore Lahiri for a lifetime of encouragement and support. This book is dedicated to the three children in our livesour daughter-in-law Vrinda; our son Karan; and, of course, Soufflwho are more precious to us than they can ever imagine. Vrinda and Karans enormous affection and interest have enriched me and my work in myriad wonderful ways, and the unconditional love of Souffl, our dog, is a constant source of joy in my life.

* * *

The following illustrations are reproduced with thanks by permission from the following sources: are drawn by Rashid Lone (University of Delhi).

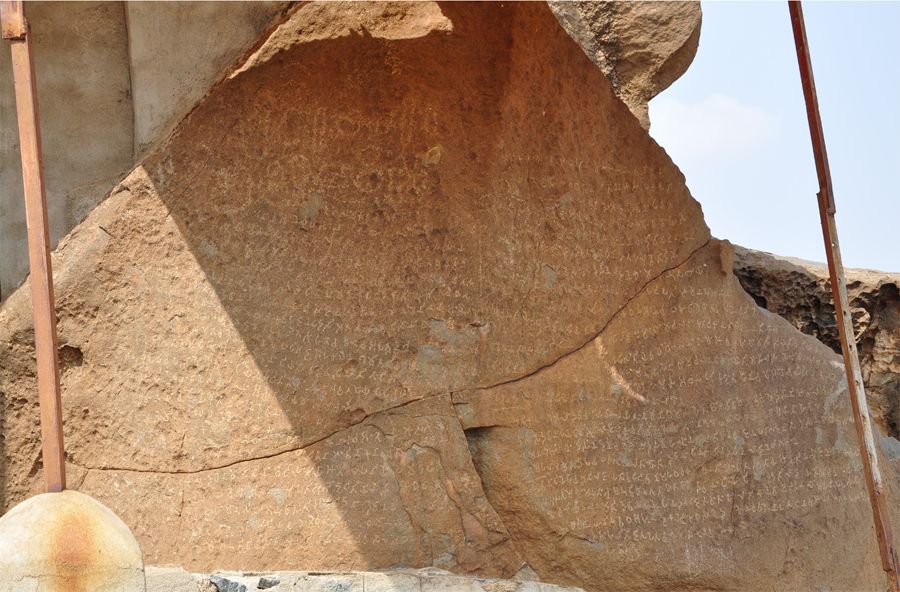

THERE IS NOTHING SPECIALLY STRIKING ABOUT THE cluster of rocks which crowns the edge of a low hilly ridge near the village of Erragudi in the Andhra region of India. From a distance the cluster appears unremarkable, while the ridge on which it sits is somewhat bare, rising out of a patchwork of cultivated fields and sparsely dotted with vegetation. The rocks on it are not imposing, standing a mere thirty metres or so above the plains. It is what one sees on the rocks at close quarters that makes them spectacular.

Cascading down the rocks is a dramatic waterfall of words. More than a hundred lines in characters of the ancient Brahmi script are imprinted across several of the boulders (). Large portions of this ancient scrawl are even now exceedingly clear, the characters boldly etched across the rock faces. Some segments have deteriorated, while a few of the lines have been defaced by modern graffiti. Yet not even the English and Telugu scribbles of contemporary visitors to this hillock can diminish the overwhelming impression of messages from antiquity created by the profusion of these ancient words. This copious transcription on rocks is part of a royal enunciation. The words and phrases that comprise it were composed by and inscribed at the instructions of Ashoka (the sorrowless one), the third emperor of the dynasty of the Mauryasand the subject of this book.

Fig. Prelude 1: Erragudi rocks as they appear from the surrounding fields

Next page

Next page

Fig. Prelude 1: Erragudi rocks as they appear from the surrounding fields

Fig. Prelude 1: Erragudi rocks as they appear from the surrounding fields