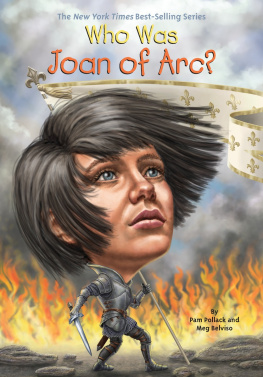

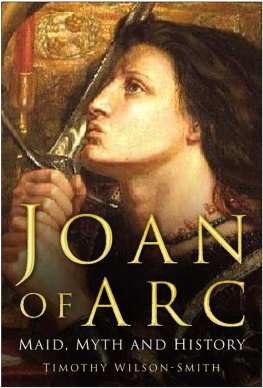

One of historys most improbable and inspiring stories began with angelic voices and visions. They were heard and seen by a young French shepherdess who could neither read nor write. What they told her was mind-boggling, yet, over time, more and more insistent: She must raise an army, liberate the city of Orlans, install a rightful French king, and drive the English from France.

In the beginning, Joan of Arc thought the task was impossible. Terrified, as any young girl would be, she finally heeded what she believed to be divine orders. During a single momentous year - 1429 she persuaded the king-in-waiting that she was truly sent by God. Then she donned a suit of armor and led the French in a string of victories over the English in the seesaw conflict that future historians would call the Hundred Years War .

Only two years later, the fortunes of Joan of Arc would take a tragic turn when she was condemned as a heretic and burned at the stake.

The Western world, however, owes an enormous debt to her. She helped to bring an end to the Middle Ages , undoing a social order built on the backs of peasants and dominated by priests, noblemen, armies, and brigands. But many years would pass before these changes became apparent.

No one knows what Joan looked like. The two remaining portraits drawn during her lifetime are crude doodles - and at least one was done by a man who never saw her. She was described as short and stocky, with dark hair, a soft voice, and a birthmark behind one ear. Later images in paintings and tapestries are more flattering, and her image over the succeeding five centuries was burnished by painters and sculptors who portrayed her as both glorious and sternly beautiful.

For a saga hinging on the fate of nations and Gods plan for the world, Joans tale unfolds in an oddly human way. Except for her, the characters are motivated only incidentally by considerations beyond power or politics. Again and again, they act - or fail to act - because of vanity, pride, ambition, petty disputes, or just plain dithering. Shakespeare would have relished the many subplots; it would have made a splendid Mozart opera. And for todays readers, the combination of a true but improbable plot with completely realized characters adds up to an engrossing story.

Joans tale is one of the most unlikely in history. The biography that follows is based on what we know to be true and the heroines own words.

Her words are central. Joans followers and foes alike took pains to write down nearly everything she said. Her remarks were preserved in royal records, church documents, court testimony, and official histories, though she herself was illiterate. There are even three letters dictated by Joan and closed with the shaky signature of someone first learning to write: Jehanne. The words she spoke convey a simple faith hitched to a keen native wit that have become an essential part of her amazing story.

On the banks of the Meuse River, in the Lorraine region of northeastern France, lies the village of Domrmy. It is a beautiful place. In the early fifteenth century, willows and cottonwoods flourished on the riverbank. Nearby stood a forbidding forest known as the Oaks or Polled Wood, where wolves and bears abounded.

The forest is featured in a mystic legend. As its most famous inhabitant later said, There is a wood in Domrmy called the Polled Wood. You can see it from my fathers door. It is not half a league away. I never heard that the fairies met there. But when I was on my journey to my king, I was asked by some if there was not a wood in my country called the Polled Wood, for it had been prophesized that a maid would come from near that wood to do wonderful things. But I said I had not faith in it.

In those days, the village was home to about forty families. Jacques dArc was a prosperous, enterprising farmer who lived in a substantial home by local standards. Its roof was made of slate, its outer walls of stone and plaster, and its floors of dirt. Jacques and his wife, Isabelle Rome, had three sons - Jacquemin, Jean, and Pierre - and two daughters, Catherine and Joan. The youngest, Joan, also known as Jehanne, entered the world on January 6, 1412.

Most of the residents of Domrmy farmed the land. It was a hard life. They grew their own food, built their own houses, and made their own clothes. In drawings and paintings from the time, women were seldom pictured absent a distaff. Distaff is still a word used to signify a female, but then it referred to a short rod with wool or flax wound around one end; whatever else a woman was doing, she held her distaff under one arm while she pulled and twisted the wool into yarn. The distaff became an emblem of womens interminable work, but not even children were free from labor.

Joans boasting about her sewing and spinning betrays a part of her at odds with the view held by the French at the time - that she was a modest, unassuming girl. In reality, she was proud and haughty.

Joans formal education was limited to religious instruction provided primarily by her mother: I learned Our Father, Hail Mary, and I Believe. This, she believed, was the only instruction a proper girl needed: I learned my faith and was rightly and duly taught to do as a good child should.

Because of all the work on the farm, Joan had considerable physical strength. She was an intelligent girl, although she had little knowledge of the outside world apart from what her father and other villagers talked about.

Her days were filled with austere duties; activities varied little from season to season. In the spring it was preparing and planting the fields; in the summer, tending the crops and herds; in the fall, gathering acorns to feed the swine; in the winter, doing whatever needed to be done to keep oneself and ones family alive. These chores were inserted into the unending toil of gardening, cooking, sewing, and repairing what was broken. Only on holidays, whether Catholic or pagan, did the drudgery cease.

From time to time, the Christian and the pagan came together. One such holiday was Laetare Sunday, the fourth Sunday of the Lenten season. It took place in the middle of a period of penitence and fasting and was intended to encourage the faithful to persevere. After attending Mass, Domrmys young people gathered at the outskirts of the forest around a massive beech tree and had a picnic of fruit and cakes. They danced, sang songs, and picked wildflowers, which they wove into garlands and laid on the branches of the towering tree.

Myth held that fairies were spotted years earlier frolicking near it - hence the name the Fairies Tree. Years later Joan vividly recalled these celebrations: Not far from Domrmy there is a tree called the... Fairies Tree, and near it there is a fountain. And I have heard that those who are sick with fever drink at the fountain or fetch water from it to be made well. Indeed, I have seen them do so, but I do not know whether it makes them well or not.... It is a great tree, a beech, and from it our fair May-branches come.... Sometimes I went walking there with the other girls, and I have made garlands under the tree for the statue of the Blessed Virgin of Domrmy.

Sometimes Joan also went to a nearby spring said to have supernatural qualities.

Later, at her trial, these childhood diversions were used against her, as many people believed this particular area of the country had served as a refuge for witches.

An unshakable belief in God was absolute for the faithful, as was the certainty that Satan posed a never-ending peril. The temporal world was a place where, in the words of one historian, good and evil, piety and heresy, the sacred and the pagan constantly warred. There was no middle ground people were believers or they were heretics. Anyone who deviated from the dictates of the Catholic Church risked being accused of witchcraft - a drastic charge given that witches were often burned alive.